SPEAKER ABSTRACTS

Opening Address: Dr Raymond Evans — renowned historian of frontier contact/conflict, penal stations, convicts, and punishment — will present ‘Convict Testimony and the Reconstruction of Penal Station Reputations’.

Closing Address: Melissa Lucashenko – acclaimed Goorie (Aboriginal) author of Bundjalung and European heritage. Her most recent novel ‘Edenglassie’ — set in Brisbane when First Nations people outnumbered colonists — questions colonial myths and reimagines Australia’s future.

Main program:

Serene Fernando, First Nations Curator, Truth Telling, State Library of Queensland

Exploring John Oxley’s Mapping of the Maiwar Through a Truth Telling Lens

This paper examines John Oxley’s journals through a critical truth telling lens, focusing on the mapping of Maiwar (the Brisbane River) and its implications on Indigenous sovereignty. By examining Oxley’s encounters with the Dhurabal people and his mapping of Maiwar, my analysis will demonstrate the importance of truth telling in reforming historical narratives. In November 1823 John Oxley encountered the convict castaway who had been saved by the local Indigenous peoples and who would lead him to the mouth of the river. His journals detail his voyage and interactions, including incidents of perceived theft by Indigenous people. However, a truth telling lens reveals these accusations of theft as ironic, given the colonial intent of cartography as a means of land seizure. In 1824 Oxley returned north with Alan Cunningham and Lieutenant Butler to establish a site for the new Penal Colony in the place the British had renamed Moreton Bay. Oxley’s journals describe violent encounters with Indigenous peoples of the area, further demonstrating the colonial entitlement and disregard for Indigenous sovereignty and human rights. Exploring Oxley’s journals through a truth telling lens, highlights the enduring truth of Indigenous spiritual and cultural landscapes. This paper advocates for the recognition of Indigenous knowledge systems and sovereignty through a new interrogation of the dominant narratives around Australia’s history and future. Truth telling fosters a more inclusive and truthful discourse on Australia’s past and its implications for contemporary Indigenous sovereignty.

Associate Professor Ben Wilson, University of Canberra

Exploring Stories of Meanjin

Researching and recreating life in Meanjin as it existed before colonisation is fraught with difficulty. The history of colonialism in south east Queensland, and particularly the missions’ movement, reveals the chief problem in exploring the stories of a place as environmentally rich and economically attractive as Meanjin/Brisbane. The Indigenous people who lived on these lands were among the first to be dispossessed and relocated in order to make way for a growing population of land hungry European immigrants . This means that many of the specifics of Jagera lore lie dormant in the ceremonial places of our people, and similarly many Indigenous people of Meanjin/Brisbane are still piecing together what it meant to be an Indigenous person living on these lands pre-colonisation, where our sacred sites were, and even which mobs we belong to. Nevertheless, much can be recovered by drawing upon the insights of history and archaeology as well as upon my own fieldwork and cultural experience. Exploring the stories of a place so heavily effected by colonisation challenges the problematic perception that Aboriginality can only exist in rural and remote locations. A study centring on Meanjin/Brisbane brings urban Aboriginality to the fore countering the idea that Aboriginal ways of being belong in the bush and cannot be replicated or even accommodated in the city. Yet for all the obvious obstacles I see the potential in modern Meanjin/Brisbane for the creation of an intercultural space where walking in country could be the foundation of a knowledge that enriches and informs all those that in their various degrees of connection merely reside in or have learned to truly inhabit the land known as Meanjin.

Adjunct Professor Brett Leavy, Queensland University of Technology and Central Queensland University

First Nations Representations of Meanjin and Maiwar – a virtual heritage story of sites and places related to the Brisbane CBD

“Maiwar in Brisbane Town” is a short video rendition of Brett Leavy’s “Virtual Maiwar,” specifically honouring the Turrabul and Yuggera people’s connection to the Brisbane CBD and the lands upon which Greater Brisbane currently exists. This project exemplifies Leavy’s dedication to preserving and sharing First Nations culture through photorealistic animations, interactive games, and augmented and virtual reality experiences. These digital realms are meticulously researched to transport audiences back in time into immersive representations of ancestral homelands, offering an engaging way to experience and connect with First Nations culture and their custodial lands. Leavy, a Kooma artist from south-west Queensland, masterfully bridges the gap between ancient traditions and modern technology through his innovative digital art. His work deeply reflects his cultural heritage, drawing from 65,000 years of wisdom, stories, and practices shared with him through the many First Nations custodians who he engages. By integrating contemporary digital tools and computer visualisation hardware and weaving these into traditional narratives, Leavy creates virtual heritage landscapes that enrich the viewer and honour First Nations ancestors whilst embracing innovation and the possibilities of these new media technologies. Leavy’s virtual heritage artworks are showcased across Australia and internationally and are more than a visual representation; each local initiative is a dynamic celebration and a call to action. In a world facing social, political, and ecological challenges, his work reminds us of the environmental stewardship and cultural resilience inherent in First Nations wisdom. Through interactive experiences, Leavy seeks to inspire reflection, recognition, and respect for Indigenous knowledge and its invaluable lessons for sustainable living and coexistence with the natural world.

Cultural Disclaimer:

Leavy’s work draws on cultural knowledge shared by various nations and clans through the Greater Brisbane metropolitan area with the local cultural heritage management agencies. All attempts have been to represent these traditions with respect and accuracy, however, this piece does not capture the full complexity of First Nations cultures. Viewers are encouraged to engage with respect and an understanding of the cultural sensitivities and intellectual property involved.

Professor Deborah Oxley and Dr David Meredith, formerly University of Oxford

“A most valuable acquisition”: How Australian Colonies Solved Britain’s Problems

The priorities of Britain’s rulers are revealed through government expenditure. There were three: (1) the Royal Navy, protecting global power and wealth, (2) the Civil List, which was the cost of a constitutional monarchy, and (3) criminal justice, to enforce domestic obedience. All three needed attention. All three would benefit from establishing a convict colony in New South Wales. It was ‘a most valuable acquisition’ as a naval port, according to Governor Arthur Philip. Co-opting Australian lands would be something of a substitute for the costly loss of the American colonies, placating an irate King. Finally, New South Wales could recreate the American Solution to the every-growing criminal justice problem. Terror could be refined in the convict colonies, indeed developed into an art form through places of secondary punishment such as Moreton Bay – and terror was critical to the redesign of a criminal justice system over-reliant on death. It is questionable whether the British state could have persisted without these vital reforms.

Professor Clare Anderson, University of Leicester

The Bigge Report and its Aftermaths in the British Empire

If Moreton Bay and its wider network of secondary punishment centres were vital to injecting terror into convict punishment in colonial New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, how were they related to carceral innovations in the wider British Empire? This paper focuses on the Bigge Report and its aftermaths as a starting point for an examination of how Australian practices impacted and shaped understandings and experiences of punitive mobility in British India and the Caribbean in the 19th and 20th centuries. The first part of the paper suggests that the Bigge Report influenced the management of Asian transportation convicts in Penang but argues that outcomes were not the same because the penal settlements of British India were situated within a very different cultural context and nexus of labour relations. The second part finds evidence of the racialisation of imperial carceral practices in an 1831 select committee, established to find ways of making penal transportation more punitive, and which debated the merits of penal transportation from Britain to Caribbean colonies. Third, the paper reveals some of the global impacts of the later Molesworth Report (1838). It argues that it stimulated the construction of a new kind of penitentiary – ‘HM Penal Settlement’ – in British Guiana and Trinidad, and informed later debates about secondary punishment and the character and potential closure of Britain’s largest penal colony in the Andaman Islands well into the 1920s.

Professor Martin Gibbs, University of New England

The Moreton Bay Carceral Landscape: An Exploration of Convict Management and Labour Networks (1823-1842)

Although discussion of the establishment of the Moreton Bay settlement in 1824 has focussed on Commissioner Bigge’s advocacy for the development of penal plantations in the ‘southern tropic’, clearly this and other ‘secondary’ punishment establishments were also seen as a means of initiating the invasion and colonisation of new regions. Importantly, the Moreton Bay settlement constituted a large network of satellite stations and work sites across the hinterland, interlinked by dynamic ‘in between’ spaces of activity. In seeking to understand the flow of people and goods between the different parts of the network, and what each component of that network did, we must understand the spatial distribution and physicality these places. Infrastructures and mechanisms of surveillance and control were used to order the convicts, and also to suppress Indigenous populations. Building upon the legacy of preceding penal settlements like Newcastle and Port Macquarie, the convicts at Moreton Bay established the region’s industrial potential and essential infrastructures, thus facilitating its transformation into the ‘free’ settlement of Brisbane. We should also consider the status of the various sites of the greater Moreton Bay convict settlement landscape and how they fared into the 21st century, and the dangers of preserving a few high profile sites while losing the majority of other places of convict heritage.

Roger Ford, PhD candidate, Griffith University

The Environmental Impact of Drought on the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement, 1824 – 1829

Australia is a dry continent. For millennia it has been subject to cycles of flooding within its river systems followed by extended periods of drought. The First Nation peoples, over thousands of years, lived with and adapted to these extreme weather conditions, preserving a rich body of climatic knowledge within oral traditions carefully passed on to subsequent generations. The European colonizers of New South Wales lacked this cultural memory and during the 1820s they suffered the consequences of their ignorance. This paper examines the impacts made by drought on the first years of the secondary penal settlement at Moreton Bay. The fundamental failure to secure a consistent supply of fresh water was a determinative factor in the 1825 removal of the initial settlement at Redcliffe to the new location on the banks of the Brisbane River, Meanjin. Three years later under the administration of commandant Patrick Logan, the effects of drought returned to Moreton Bay with even greater levels of devastation. A near total lack of rain across the colony led to crop failures, barren pastures and contaminated water supplies. With rations cut by half, the Moreton Bay convict labour force experienced epidemics of dysentery, fever and ophthalmia resulting in multiple casualties. This paper addresses how the colonial authorities reacted to this unfolding catastrophe, and the apparent reluctance of many later historians to recognize the fundamental significance of environmental factors within the mythos of convict Australia.

Professor Jane Lydon, University of Western Australia

Legacies of British Slavery in 1880s Meanjin/Brisbane

A decade before Britain abolished slavery, it established a penal settlement in Meanjin, on Jagera Turrbal Country. Following the recommendations of John Bigge, fresh from reforming Trinidad’s slave system, authorities sought to create a harsh regime of punishment that echoed that of Britain’s Caribbean colonies. Fifty years after abolition, slavery’s legacies in the form of ideas and arguments continued to shape the colony: the battle over the use of non-white labour by Queensland sugar planters reached a climax in 1885, opposing two elite heirs of Caribbean slavery. His Excellency the governor, Sir Anthony Musgrave (1828-1888), son of an Antiguan slave-owner, was detested by sugar planters for his ‘ultra Exeter Hall leanings and advocacy of Imperial in preference to Colonial dominancy in New Guinea and the South Pacific’; they attacked ‘Mr. Griffith’s willingness, in his abject deference to pseudo-philanthropic influences’ to comply with imperial authority. John Ewen Davidson (1841-1923), legatee of a staggeringly wealthy slave-owning dynasty, led the northern sugar planters in the pursuit of separation and non-white labour. In the context of recent debate regarding the responsibility for frontier violence of prominent politicians such as Samuel Griffith (e.g., Reynolds 2021, Finnane and Richards 2023, Evans 2024), Musgrave’s advocacy for the protection of non-white labour must be acknowledged. Davidson’ rigid beliefs regarding biological race can be understood as part of his Caribbean heritage (Christopher 2020, 2021). While both men believed in non-white labour for the tropics, this 1880s clash between Musgrave and Davidson demonstrates divergent post-emancipation trajectories after abolition.

Associate Professor Ray Kerkhove, University of Southern Queensland

Forgotten Biographies: Reconstructing Key Indigenous Figures and Conflict Incidents of Convict-Period Queensland

South East Queensland at the time of the penal settlement comprised a number of First Nations communities totalling many thousands of individuals, who had complex interactions with each other. Early records reference many of these – especially leading figures, whose relations with the colony often had broad consequences for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Despite this, relatively little work has been attempted to reconstruct these figures and their role in some of the main conflicts and developments of this time. This paper reconstructs some of these conflict incidents; the lives and interactions of Old Moppy, Mulrobin, Eumundi, Eulope, Mullan, the ‘Duke of York’ and other important Indigenous leaders, and their impact on the colony’s history.

Jan Richardson, PhD candidate, Griffith University

‘Other’ Black Peoples: Rethinking Race and Settler Colonialism in Australia’s Northern Tropic

This paper re-examines settler colonialism in Queensland through the experiences and voices of non-white convicts from African and South Asian ethnic backgrounds. Among them were those who interacted and lived with Indigenous peoples of Queensland and northern New South Wales, learning their languages and traditions, and acting as conduits, mediators and interpreters. Recovering their stories provides a significant opportunity to evaluate and complicate the interplay of race and settler colonialism in Australia’s northern tropic. The stories of Sri Lankan convict George ‘Black’ Brown and Indian convict Sheik Brown, runaways who spent long periods living with First Nations groups, forming families and gaining knowledge of Indigenous languages, customs, and laws are relatively well known. However, those of later arrivals — including fifteen Mauritian convicts sent to Moreton Bay in early 1840 and two Khoisan (‘Hottentot’) convicts who joined Moreton Bay’s Border Police in 1843 — are more obscure. Many years later, the Mauritian Benedict Vengeur described local First Nations peoples ‘as being terribly treacherous in those days’ and said that ‘he himself had, on three different occasions, very narrow escapes, as the aboriginals [sic] did not’, in his words, ‘“take to his colour at all”’. In contrast, Eugene Doucette lived with Aboriginal communities at Kangaroo Point and on Stradbroke Island/Minjerribah, acting as an interpreter and liaison with white settlers. The varied experiences of non-European convicts at Moreton Bay speak not only to a complex racial past, but also to the uncomfortable and often unacknowledged space between white settlers and First Peoples on the Queensland frontier.

Associate Professor David Roberts, University of New England

Colonial Gulags and the Law of Exile: The Piratical Seizure of the Brig Wellington, 1826-1827

“The Laws of England were not made for Convicts” (Governor Ralph Darling, 1828)

In December 1826, convict passengers being transported on the brig Wellington from Sydney to Norfolk Island seized control of the vessel and made off, remaining at large for several weeks until they were retaken in the Bay of Islands, returned to Sydney and put on trial for their lives. The episode evokes the strong themes of escape and liberty that pervade our memories of nineteenth-century New South Wales. But principally this is a story about English law, as it pertained to colonial penal stations such as Moreton Bay. Historians have long been fascinated by the histories of the colonial gulags – special places of deterrence and terror that laid bare the darkest workings and ideologies of the British-Australian convict system. What has not been so well comprehended is the challenging legal conundrums posed by those stations, for as places of internal exile they raised a surprising array of very searching questions — regarding the status of doubly-convicted British subjects, for example; about the jurisdiction of colonial courts and the local executive; and importantly about the meanings of internal banishment in the context of English transportation law. Indeed, those questions only occurred to the contemporary authorities incrementally and amid confusion and uncertainty from the mid-1820s. The trial of the Wellington pirates in Sydney in February 1827 was a key moment of revelation and clarification, sharpening contemporary understandings of what Moreton Bay and other stations actually were, and of what it meant to be, as one convict described it, ‘banished in this land of exiles’.

Tamsin O’Connor, Adjunct Lecturer, University of New England

“These were not particular times”: Testing the Boundaries of Coercion and the Limits of Resistance at Moreton Bay 1824-1842

Alan Atkinson observed that there have always been two ways of remembering convict life: “as normal for the time or else revoltingly evil.” In either case the penal stations have not fared well — being easily dismissed as the self-evidence of evil or as the experiential aberration of normal. To be sure a catch-all brutality associated with penal station life is emblematic of convict society in many popular accounts, but the complex meanings and mechanisms of the systemic power behind that brutality, and the equally complex convict responses to it, have all too often been left unexplored or, at best, couched in simple terms of individual tyranny and habitual recidivism. While the once commonly held assumptions about the nature and apparent paucity of convict resistance have been substantially challenged, not least by Hamish Maxwell Stewart, a degree of misrepresentation and even incuriosity persists. The normalising account of convict life in New South Wales essentially doubts the very existence of a coercive space except that which is conveniently corralled on the remote penal stations — which are invariably marginalised as statistically insignificant. Thus, negating the purpose and persistence of convict resistance and rebranding it as a function of (bad) character rather than as a consequence of coerced labour. This paper will argue that the misrepresentation of the convict response at Moreton Bay derives from an incomplete understanding of the function and operation of those penal stations established in the wake of the Bigge Report to discipline and awe a subordinate class of unfree labour. I attempt to make sense of the often bewildering variety of male convict responses at Moreton Bay by demonstrating the relationship between the components of the punitive system and the different reactions they provoked. Three categories of response will be isolated: collaboration, ‘silent service’ and resistance. The nuances and ambiguities of each will be examined, with the lion’s share going to the variables of resistance. I draw upon the theoretical insights of scholars of other unfree societies and the still relatively silenced voices of the men of Moreton Bay.

Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart and Roxane Giles, PhD candidate, University of New England

The Political Economy of Penal Labour Revisited

This paper uses digital data to flesh out the theoretical literature on the role of penal stations (including Moreton Bay) in regulating work and punishment in colonial Australia. It identifies convicts who served time in penal stations and explores their outcomes in relation to those who escaped service in these forbidding institutions. A central purpose of the paper is to identify the prevalence of penal labour sentences and their impact on the political economy of labour exploitation in colonial Eastern Australia. Its three central questions will explore: Who was sent to a penal station and why? Reveal the extent to which the treatment they received differ from that meted out at other sites? Evaluate the impact of time spent in a penal station on life expectancy? The paper will conclude by attempting to position penal stations within an overall understanding of the impact of convict labour on the wider process of colonisation.

Dr James Bradley, University of Melbourne

Representing Convicts: Thirty Years on

Concluding comments reflecting on the breadth and depth of papers on first contact and convict historiography presented at the symposium before we launch into the final fabulous session chaired by Professor Anna Johnston on Literary Representations of Meanjin and Moreton Bay and concluding with Melissa Lucashenko’s Closing Address.

Associate Professor Maggie Nolan and Mahalia Mozes-Pettit, Bachelor of Advanced Humanities (Hons), University of Queensland

Literary Representations of Meanjin and Moreton Bay, 1824-2024

According to the AustLit database, Australia’s bio-bibliographical database housed at the University of Queensland, there are over 700 novels that have been set in Brisbane Meanjin since the founding of the Moreton Bay colony. The earliest of these is William Ross’s The Fell Convict, or, The Suffering Tyrant: Showing the Horrid and Dreadful Suffering of the Convicts of Norfolk Island and Moreton Bay, Our Two Penal Settlements in New South Wales: with the Life of the Author William R—S, published in 1836, which focuses on the effects of the founding of the colony on its convicts. Further literary representations of Meanjin didn’t emerge until the late nineteenth century. Even later, there are very few representations of Moreton Bay colony in the Australian literary tradition. In recent times, there has been a surge of novels set in Brisbane, including Melissa Lucashenko’s widely celebrated novel Edenglassie (1823) that returns to the founding of the colony from an Indigenous perspective, offering a new way of thinking about the impacts of the colony on First Nations Australians. This paper scours the Austlit database to look at the shifting literary representations of Brisbane Meanjin over time, with an initial focus on novels. It explores the role of the city in Australia’s literary landscape and how recent interventions, such as Lucashenko’s, have the potential to reshape our understanding of the history of the city in the 200th year of the founding of the penal colony.

To view speaker, presenter and chair biographies, click here.

For further information about the Bicentennial Symposium, click here.

To register, please visit the Symposium website.

To register for ‘In Convict Footsteps: A Bicentennial Event’ at the Commissariat Store Museum on Thursday 12 September 2024, 6.00pm – 7.30pm, click here.

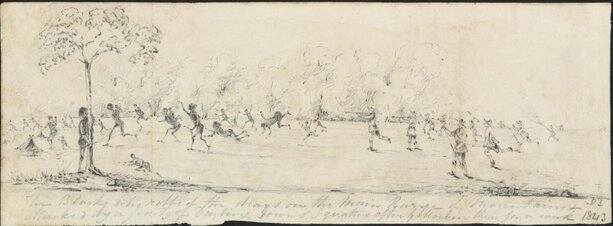

Image (above): Domville Taylor, Thomas John (1843). Squatters’ attack on an Aboriginal camp, One Tree Hill, Queensland, 1843. Source: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-151763386.