Robert Henry (Harry) Gentle

(1920-2015)

Growing up in the Depression

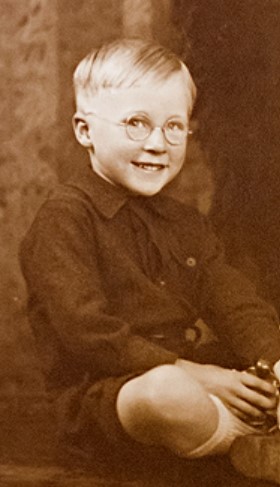

Harry Gentle was born 3 February 1920 at St. Lawrence Private Hospital, Chatswood, Sydney, as one of four children of New South Wales grazier Robert Delisle Gentle, and Eileen de Vis Connor. Eileen was the daughter of a genteel family in Lismore, where her father was a medical doctor. The Gentle family property at Stockinbingal north of Wagga Wagga was named after Balcchraggan in Scotland, the home of Gentle’s father.

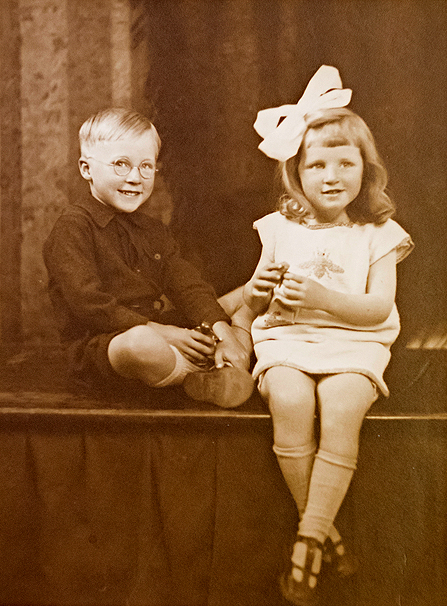

The economic pressures of the Great Depression were to imprint themselves on Harry’s early life. The grazing property was sold around 1925 and the Gentle family was set adrift with the growing numbers of sundowners seeking employment in the rural and northern hinterlands. Harry and his sister Janet were left with aunts at Dinga Dingi near Stockingbingal while their parents moved further north to set up a saloon and barber shop at Dorrigo, inland from Coffs Harbour. The business failed so the family moved north again, to the tropical Tully region in North Queensland, where Robert Gentle tried his hand as a share farmer growing bananas and beans. Young Harry briefly attended the Tully primary school and then continued his schooling by correspondence as the family relocated several times.

The economic pressures of the Great Depression were to imprint themselves on Harry’s early life. The grazing property was sold around 1925 and the Gentle family was set adrift with the growing numbers of sundowners seeking employment in the rural and northern hinterlands. Harry and his sister Janet were left with aunts at Dinga Dingi near Stockingbingal while their parents moved further north to set up a saloon and barber shop at Dorrigo, inland from Coffs Harbour. The business failed so the family moved north again, to the tropical Tully region in North Queensland, where Robert Gentle tried his hand as a share farmer growing bananas and beans. Young Harry briefly attended the Tully primary school and then continued his schooling by correspondence as the family relocated several times.

They moved from Tully to nearby Murray Upper, then in 1929 to Euramo (about ten kilometres north of Murray Upper), where Harry’s father tried to run a shop which failed in 1930 when too many of its customers were running up excess credit. In 1933 they moved back to the Murray Upper and settled at Kennedy No 2 Road Camp (most likely a road camp for labourers constructing the Bruce Highway) where the experience of running a shop was repeated. During this period in the north Eileen Gentle felt her loss of status in comparison with others who had not been displaced, such as their neighbour, Joe Olley, whose daughter Margaret was to become an Australian icon.

In 1935 the family moved to Brisbane, where fifteen-year old Harry had to work for his keep. Further education was still not an option. Like his father, Harry became apt at reinventing himself. At one stage he worked as a magician’s assistant, travelling around Queensland schools, and when he enlisted in 1939 described himself as a shop assistant resident in Highgate Hill.

Military service

As soon as he turned 19 Harry volunteered for overseas service in the Commonwealth Military Forces, in February 1939. He was trained in signals at Fort Lytton and served for a brief period at Victoria Barracks in Brisbane. In August 1940 he was transferred to Charters Towers as Sergeant Signal master to run a small signals office supporting several army units in the area. To encrypt and decrypt communications on 24-hour standby, they operated out of a small shop in Gill Street with the office at the front and accommodation at the rear of the building, attending meals at the local mess. Telegraphic messages were received and sent through the Postmaster General’s telegraph office and their desk had a telephone switchboard and a Despatch Rider Letter Service for official mail, which was couriered daily between Charters Towers and Townsville. ‘We were young and healthy and were able to handle our fairly taxing duties and still have reserves of energy available for participation in the social side of life.’²

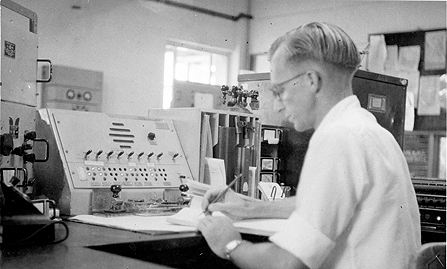

From 1943 Harry served as Signals Watch Supervisor in Townsville – a period he described as one of relative laxity and about which he left a detailed memoir supplemented by the memoir of one of the women also working there. The signals office was in the Stuart primary school, and right next to the signals office was the Postmaster General’s ABC Radio monitor, which occasionally provided entertainment for the staff working on three shifts around the clock. The signals office leased landlines from the Postmaster General to communicate with Cairns and Brisbane via English Creed Teleprinters. It also had a busy telephone switchboard, a Despatch Rider Letter Service for mail, and one or two morse code radio links.

Each shift had an Officer, a Sergeant and a Corporal, and a typist and a sender to send messages, and a receiver and four transcribers to receive messages via the Wheatstone Bridge Automatic morse circuit. This typewriter transcribed messages into morse code by punching dots and dashes onto narrow strips of paper. This fast communication method was intended to link Cape York and Port Moresby, but the underwater cable across Torres Strait kept breaking, rendering the Wheatstone useless for much of the time.

The women excelled in keyboard operation so that Harry found ‘it was a pleasure to watch them in action’. World War II offered unprecedented numbers of women the chance to work in responsible positions, often filling roles that had been considered the domain of men. Working in close proximity with women was an unusual situation for inexperienced Harry. The women were accommodated in a house near the signals office and the men in tents about two kilometres down the road near a US transit camp where the men fraternised with American GIs trading cigarettes and beer. The motley crew of characters included maintenance mechanic Dick Moustakis, known for heavy drinking, who boasted himself a Communist, had a poster of ‘Uncle Joe’ (Stalin) on his wall, and reputedly ‘changed his name to Moustaka to sound more Russian’.4

Soon the makeshift signals office at Stuart was replaced with ‘a much grander affair’ at Roseneath out of town, in a reinforced air raid shelter built into the side of a hill. At Roseneath the women’s dormitory was to one side of the hill, ‘forbidden to men’, and the men were in tents on the other side, with the orderly room, catering services and stores in between, and nobody ‘dared to cross the boundaries’. The top of the hill, on the other hand was ‘neutral territory’ for joint outings and events, and lifelong friendships were forged among the staff of the signals office’. Harry remembered by name Rona Burcher, Mavis Searle (later Truscott), Elrae Nelson, Betty Goodsell, Joan McKinlay, Jan White, Gladys Curnow, Doreen Sticher, Pat Hill and a woman by the name of Hunt, as well as Reg Kidd, Stewart Wallace, Tassie Wilinson, Harry Tanzer, Herb Groth, Arthur Jobling and Dick Moustakis.

The Roseneath facility had an extra one or two keyboard circuits, mostly US Teletypes, and a Wheatstone ‘which actually worked on occasion’. Harry found that ‘Our radio links were quite inadequate and generally unreliable’ so sometimes messages were relayed as paid telegraphs instead. The communications problems were compounded through disruptions to the PMG lines through floods or roadworks. Sometimes the signal staff had to bundle up their documents to work in the Central Telegraph Office instead. On one such occasion, the civilian CTO supervisor, ‘an avuncular old fellow’ unused to the comradely interactions with army women, objected to one of the women putting her feet up on a desk while working in the early hours of the morning. It was not the feet on the desk, or the leaning back in a chair, that he objected to, but to the ‘goodly show of shapely upper leg’ that resulted from it.

One of the women in the signal office later wrote that her eighteen months in Townsville were the best part of her army experience and she ‘enjoyed every bit of it’ despite the unbearably hot drinking water that came from the rainwater tanks, and the dengue fever that affected the staff. The Pallarenda hospital, damaged by a cyclone, was reduced to a tent encampment with sand floors ‘not a very nice place and the matron was a real tartar.’5 However there were periods of recreation at Magnetic Island, dances and visits to town staying in the YMCA.6 Despite such laxity, Harry emphasised that ‘the remarkable aspect of the whole experience is the exemplary sexual behaviour of all concerned’. As sergeant he had some responsibility for the good conduct of the team, and opinions on his leadership apparently differed between his superiors and the people in his charge. In 1944 he was twice reprimanded for ‘neglect to the prejudice of good order and military discipline’. One of the Majors judged him as ‘quiet, pleasant, sincere and conscientious, hard worker, no drive, cannot control men.’7 One of the AWAS women stationed at Townsville wrote, however, that ‘our female officer was Lt. Margaret Reynolds and one Sgt. Harry Gentle who were just wonderful to work with.’8

In August 1945 Harry Gentle was posted to Lae (PNG). He arrived back in Townsville in February 1946 and prior to his discharge in June 1946 he attended a three-month School of Signals course where senior instructor Major Nicholls judged him ‘cleverest all round student on the course but would not make a leader’. He was awarded an Australian Efficiency Medal in November 1946 for 64 months of loyal service.

Public Service and Retirement

His military training, still the only education he had received, was to shape Harry’s civilian life. He became a Communications Officer in the Department of Civil Aviation in 1948, and was posted to Tennant Creek and Darwin, where he married Alice Charlotte Hedwig Peckman on 30 January 1956. The marriage remained childless. They stayed in Darwin until 1965, and then moved to Manly in Sydney, still in the service of the same Department, now the Department of Transport.

They spent a period in Melbourne, and in the 1970s Harry was posted to Port Moresby, from where he returned to Melbourne just before his retirement. He began contemplating his dream of further education. Earlier he had purchased at a cheap price some of the Poseidon shares that became notorious as a stock market bubble that burst in 1970 and, being childless, began to reflect on leaving some of his modest wealth to a worthy cause.

In 1980, now aged sixty, he retired in Benowa on the Gold Coast and became a mature age student at Griffith University, founded as an interdisciplinary, alternative university in 1975. This fulfilled a life-long dream of further education. Harry garnered High Distinctions in several subjects and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in April 1984.

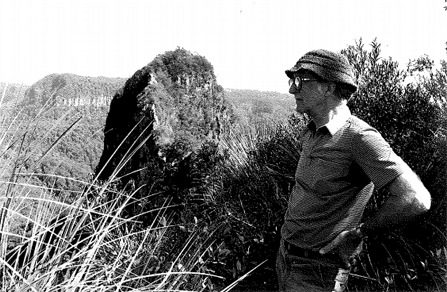

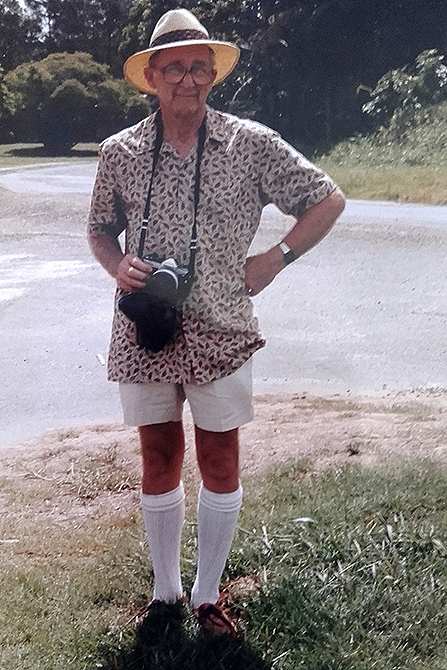

He became a volunteer at the Gold Coast Library, became active in the University of the Third Age (U3A) and pursued his passion for photography as a bush walker. His love of the outdoors also led him to support the anti-logging protests of the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO). Eventually he became the full-time carer for his wife Alice until she moved into the Golden Age Aged Care facility, where Harry himself later followed.

Harry died just five days short of this 95th birthday, on 29 January 2015.

1 Harry Gentle ‘Brief – very brief – Recollections of Townsville Signals’, Manuscript, Gentle Family collection, undated.

2 Harry Gentle ‘Brief – very brief – Recollections of Townsville Signals’, Manuscript, Gentle Family collection, undated; and, Memoir by an unnamed member of the AWAS in the possession of Harry Gentle, undated.

3 Memoir by an unnamed member of the AWAS in the possession of Harry Gentle, undated.

4 Memoir by an unnamed member of the AWAS in the possession of Harry Gentle, undated.

5 Harry Gentle military records, Gentle Family collection.

6 Memoir by an unnamed member of the AWAS in the possession of Harry Gentle, undated.