Project Outline

Digital dialogues on diet: harvesting the archive for alternative patterns in Queensland food culture investigates Queensland’s colonial history through food. The drive to seek food in known and unknown landscapes extends beyond the bowl and the fire, enabling deep inquiry on cross-cultural exchange, exploitation, and resistance. We find in food broader questions of landscape, people, and the sometimes-prickly coexistence of the human and non-human world.

This project is a meeting of disciplines. Our collaborative engagement and cross-disciplinary activity—one researcher working in archaeology, the other engaged in practice-led creative research—sparked significant moments of conversation and engagement. The outputs we present here explore tangential lines of inquiry borne from a shared pool of resources.

Georgia Rolls’ essay, ‘The politics of food: Oysters, Indigenous knowledge, and colonial exploitation’, uses newspapers, historical photographs, and cultural artefacts to investigate diverse cultural approaches to harvesting the natural world. Artistic representation and archaeological techniques, including carbon dating, oral histories, and the press, reveal how food indexes different knowledge creation, exchange, and colonial power and politics.

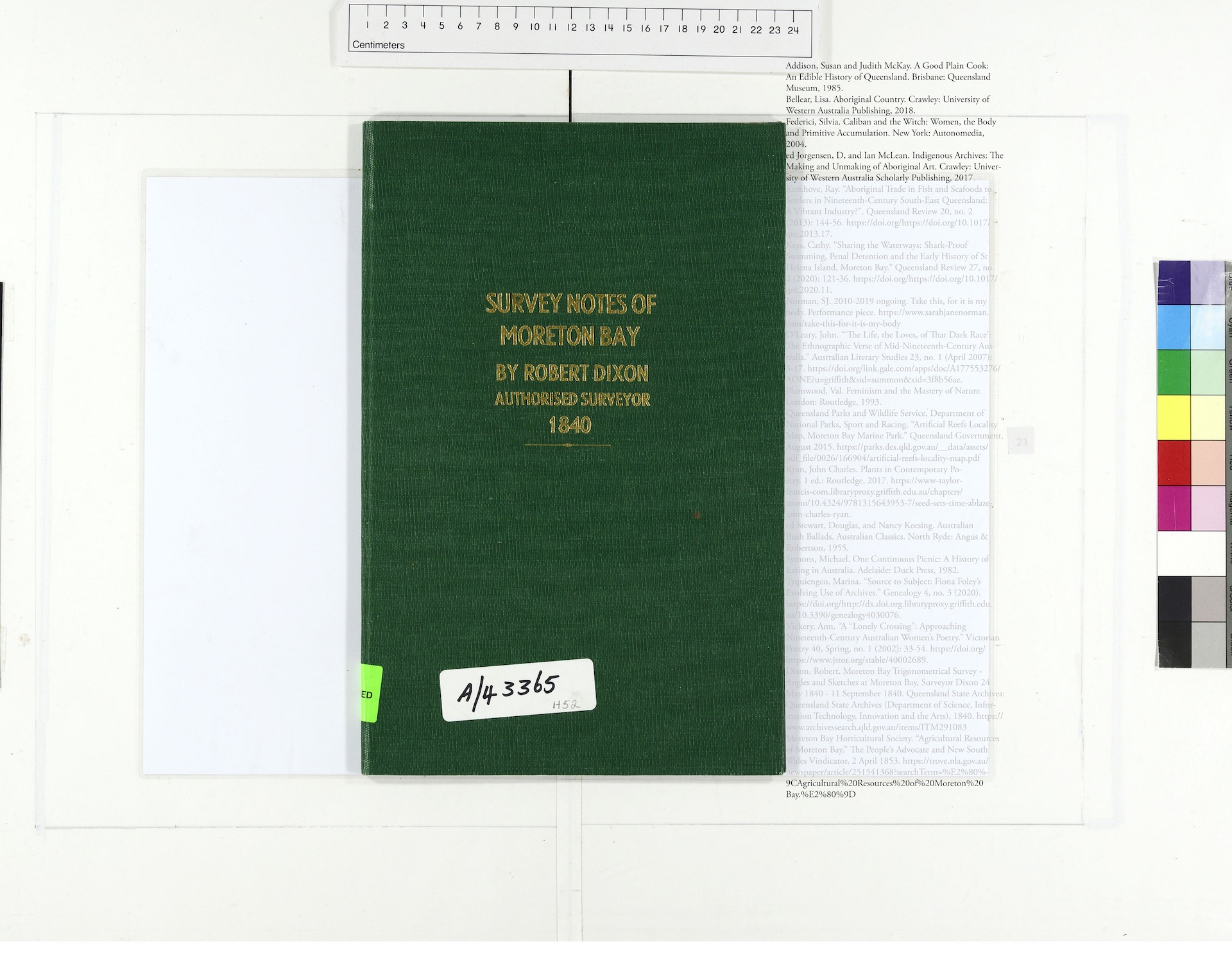

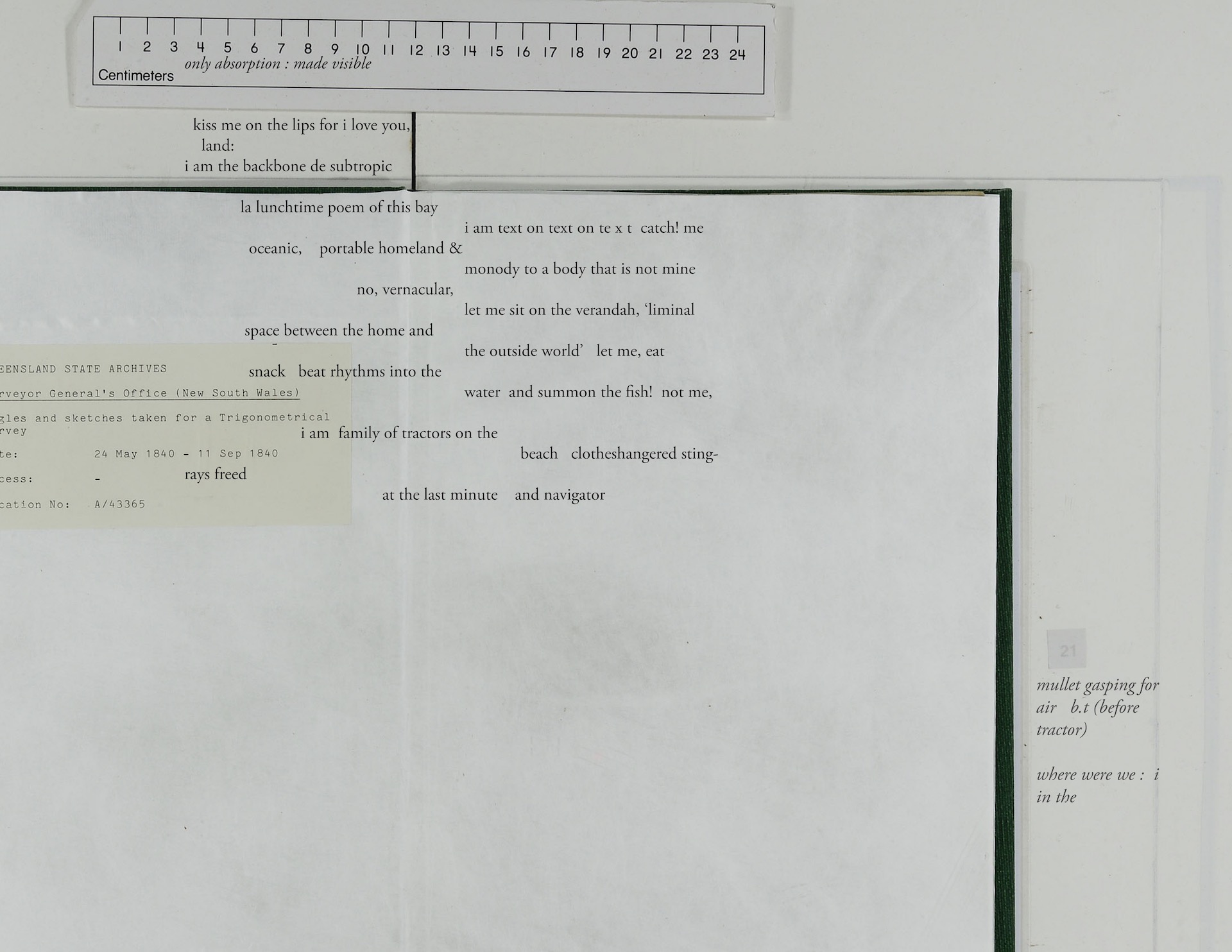

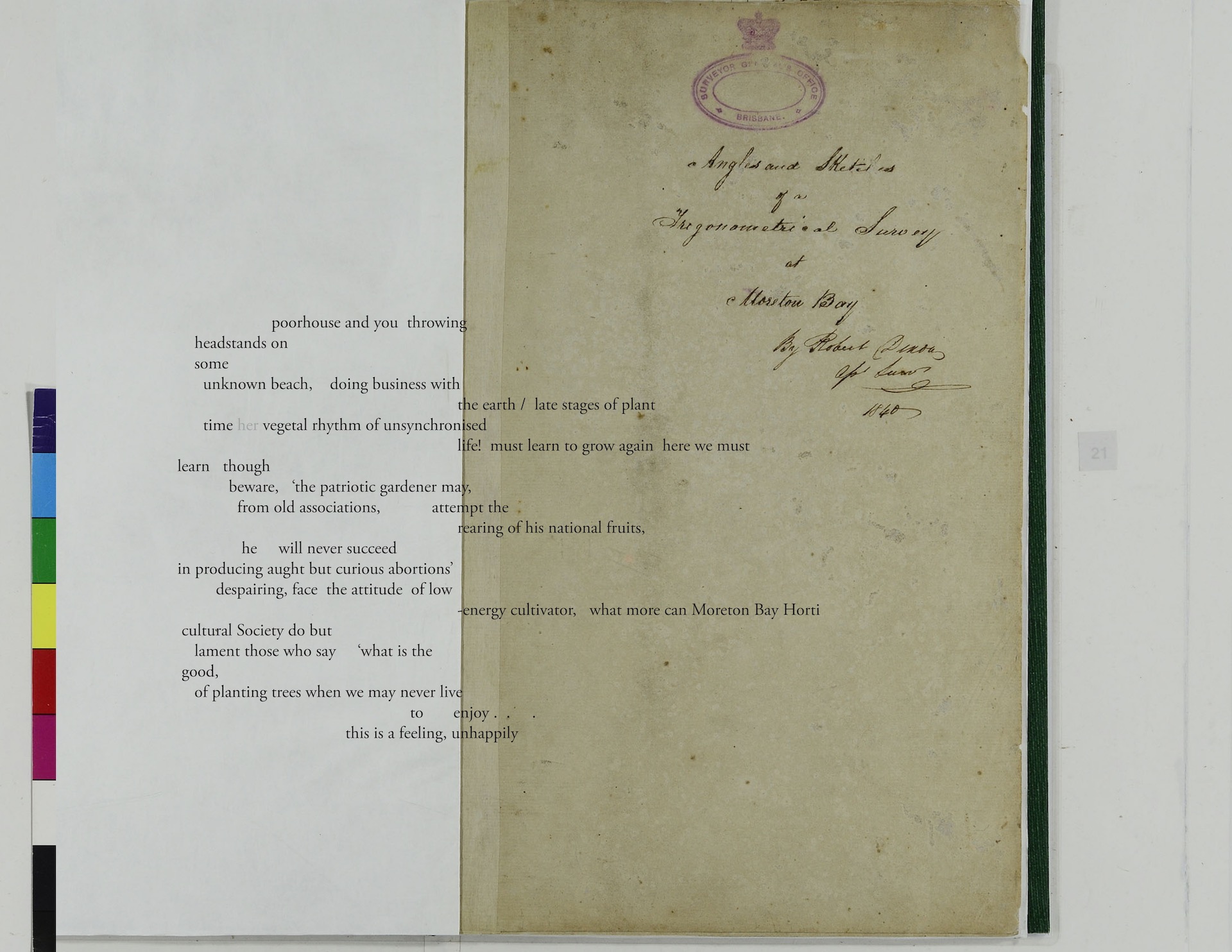

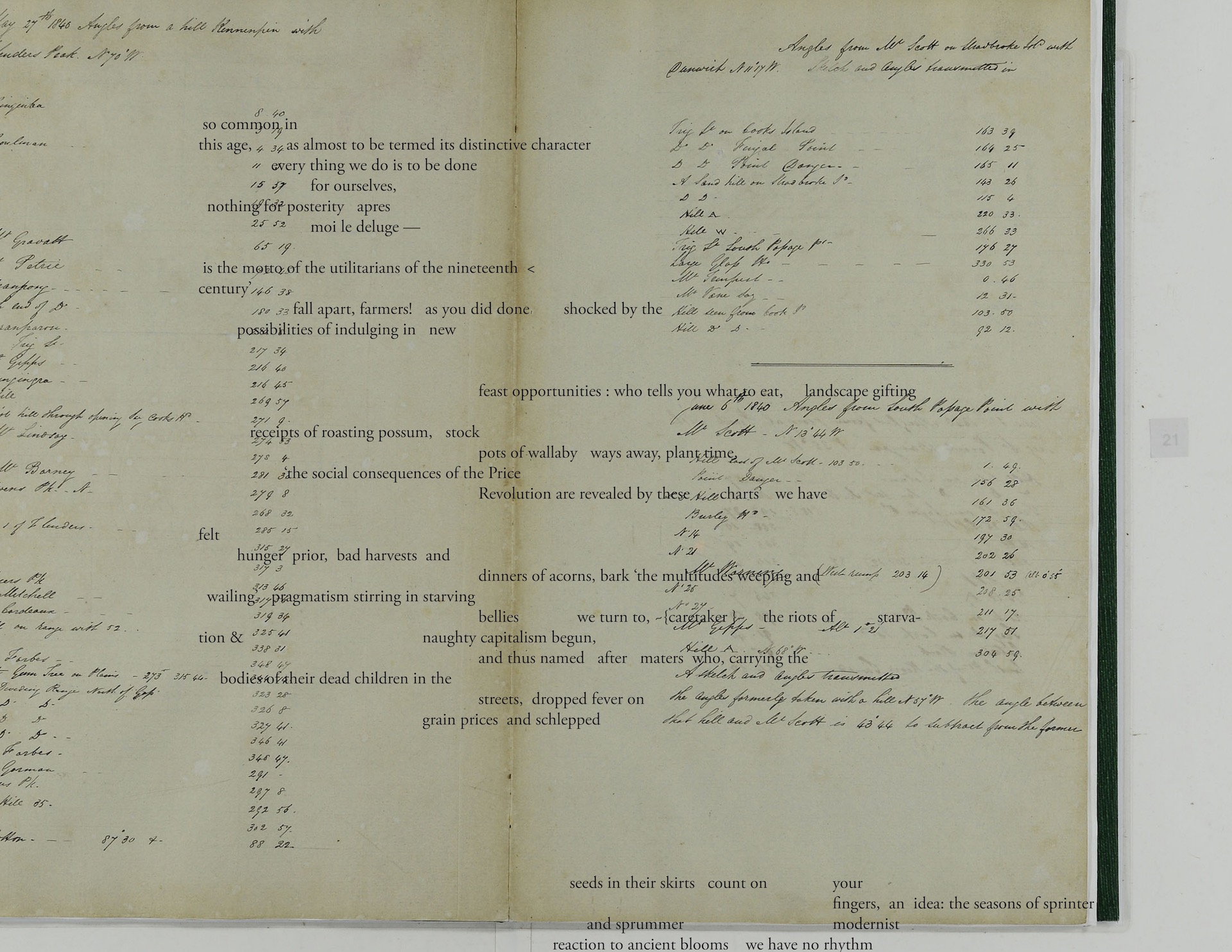

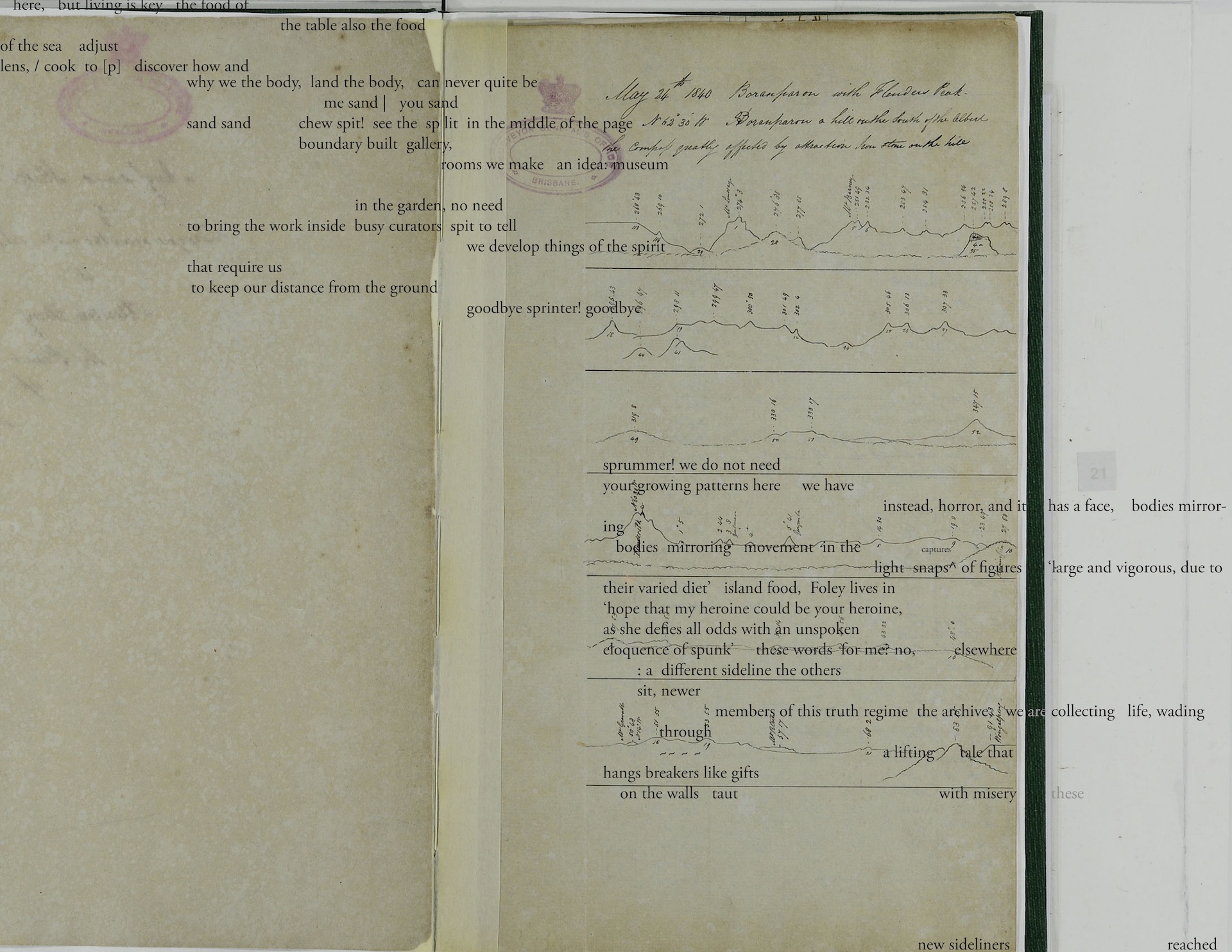

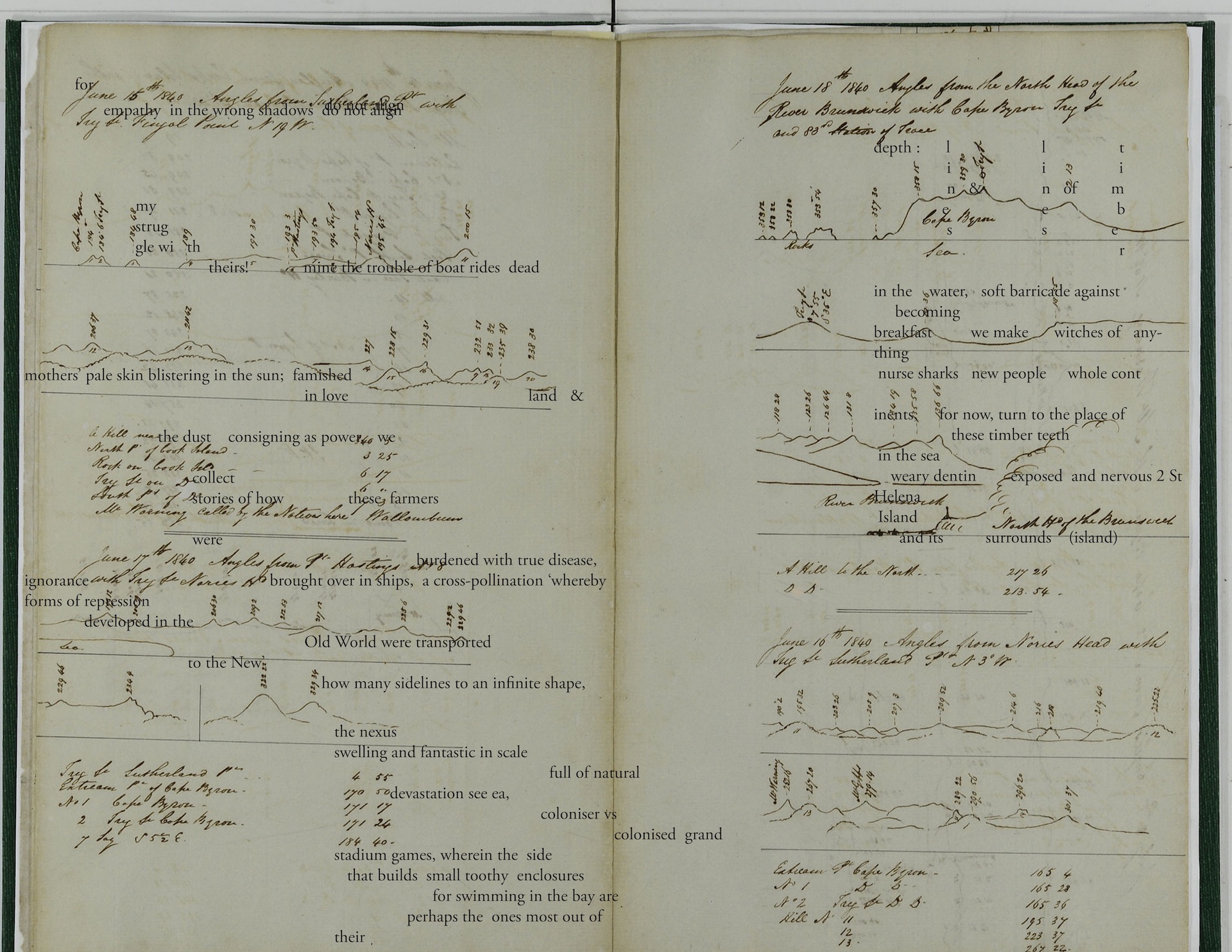

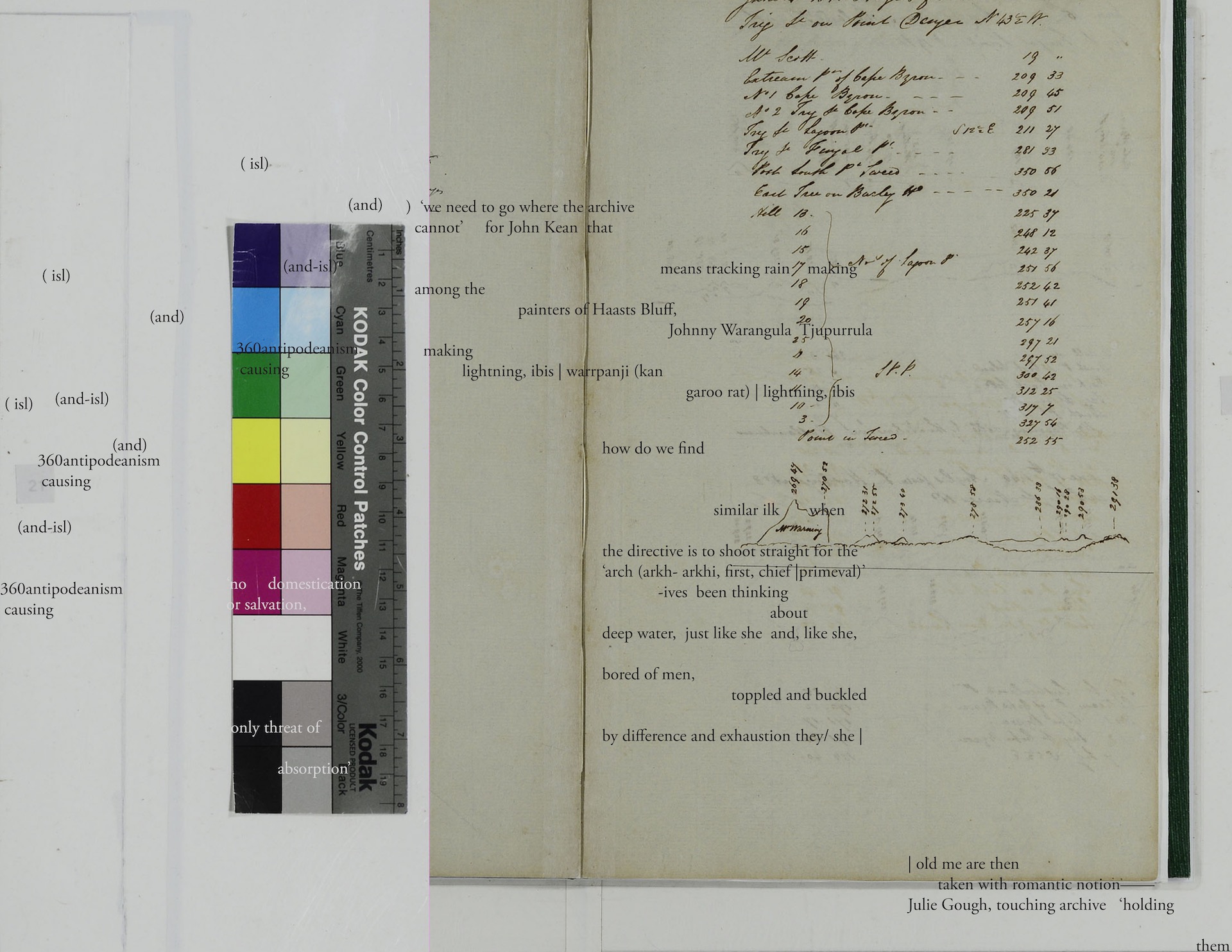

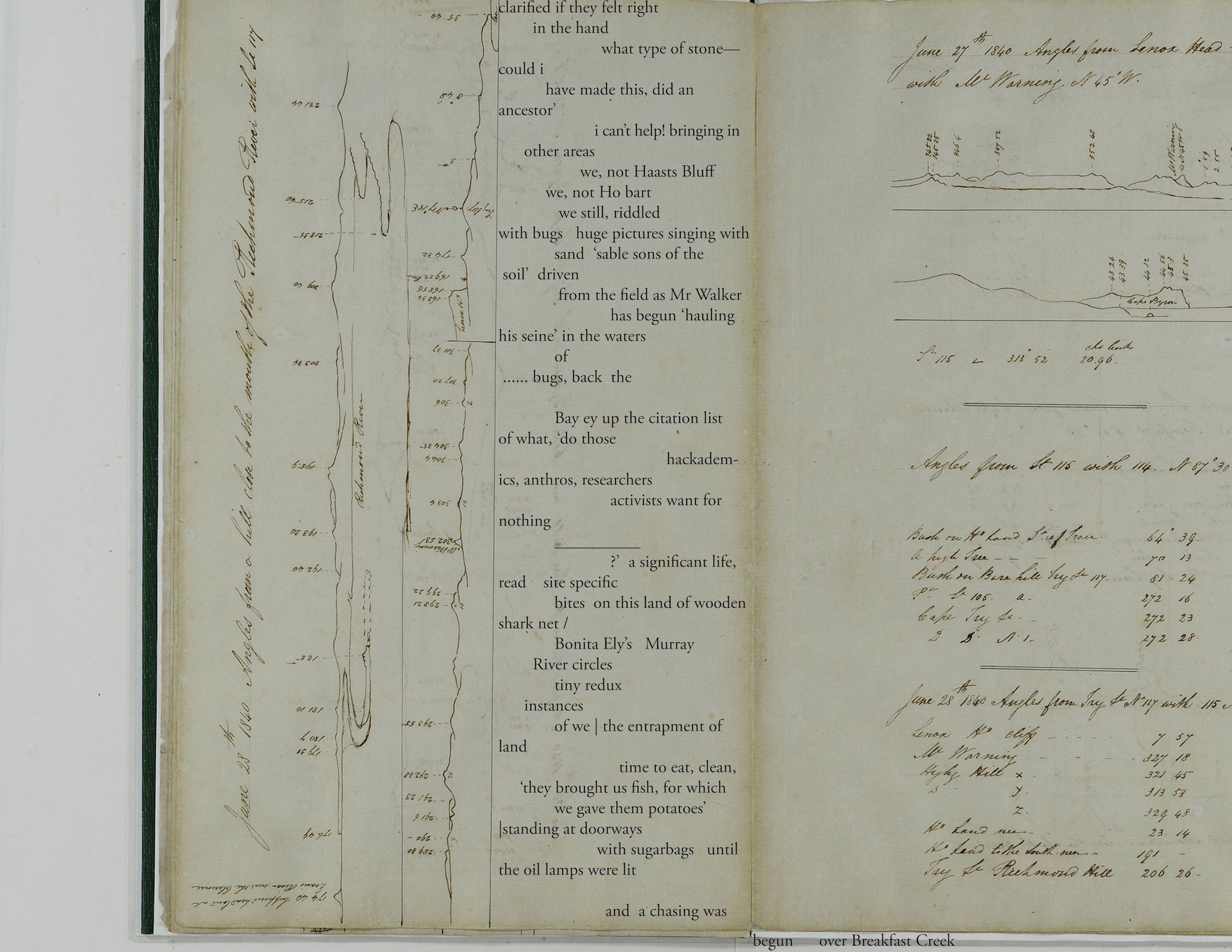

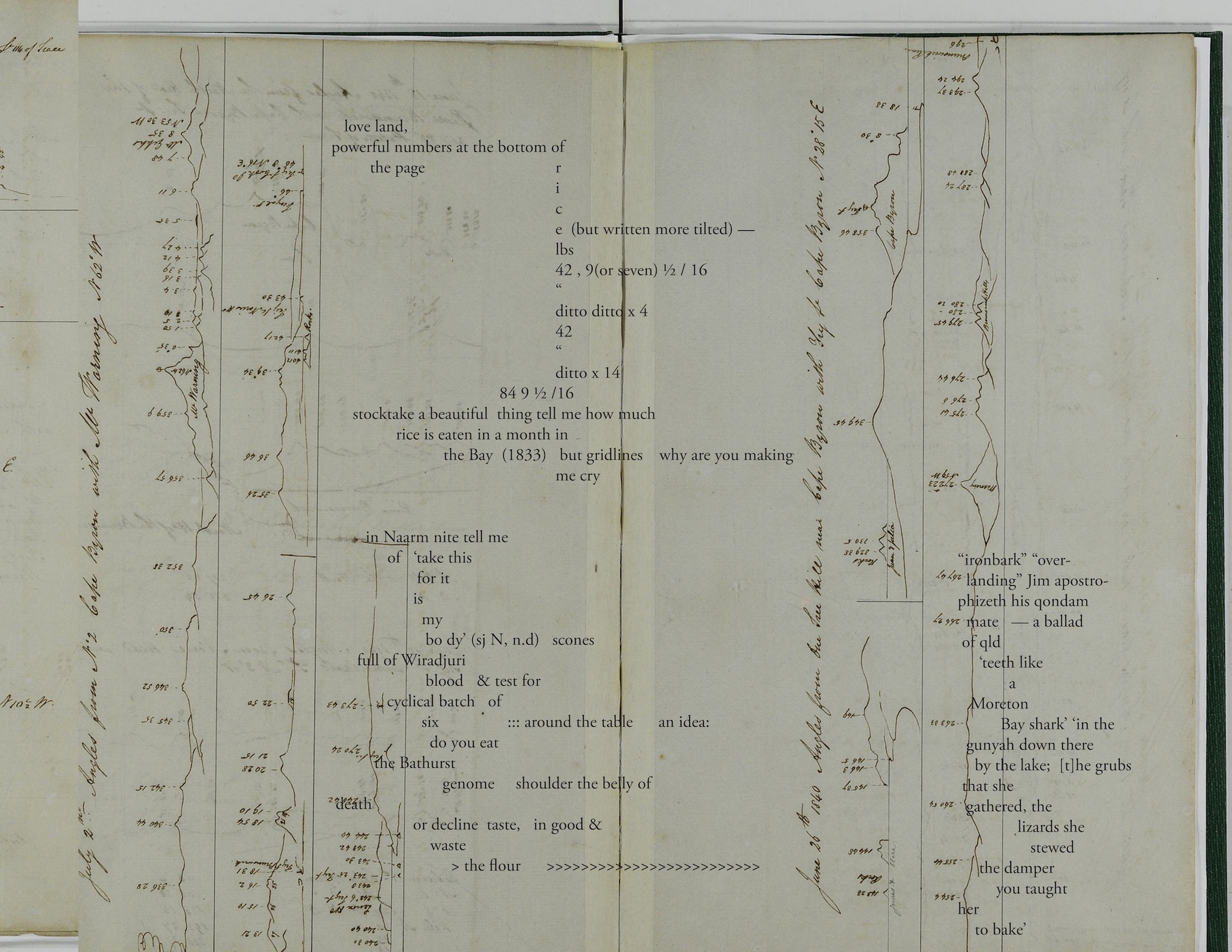

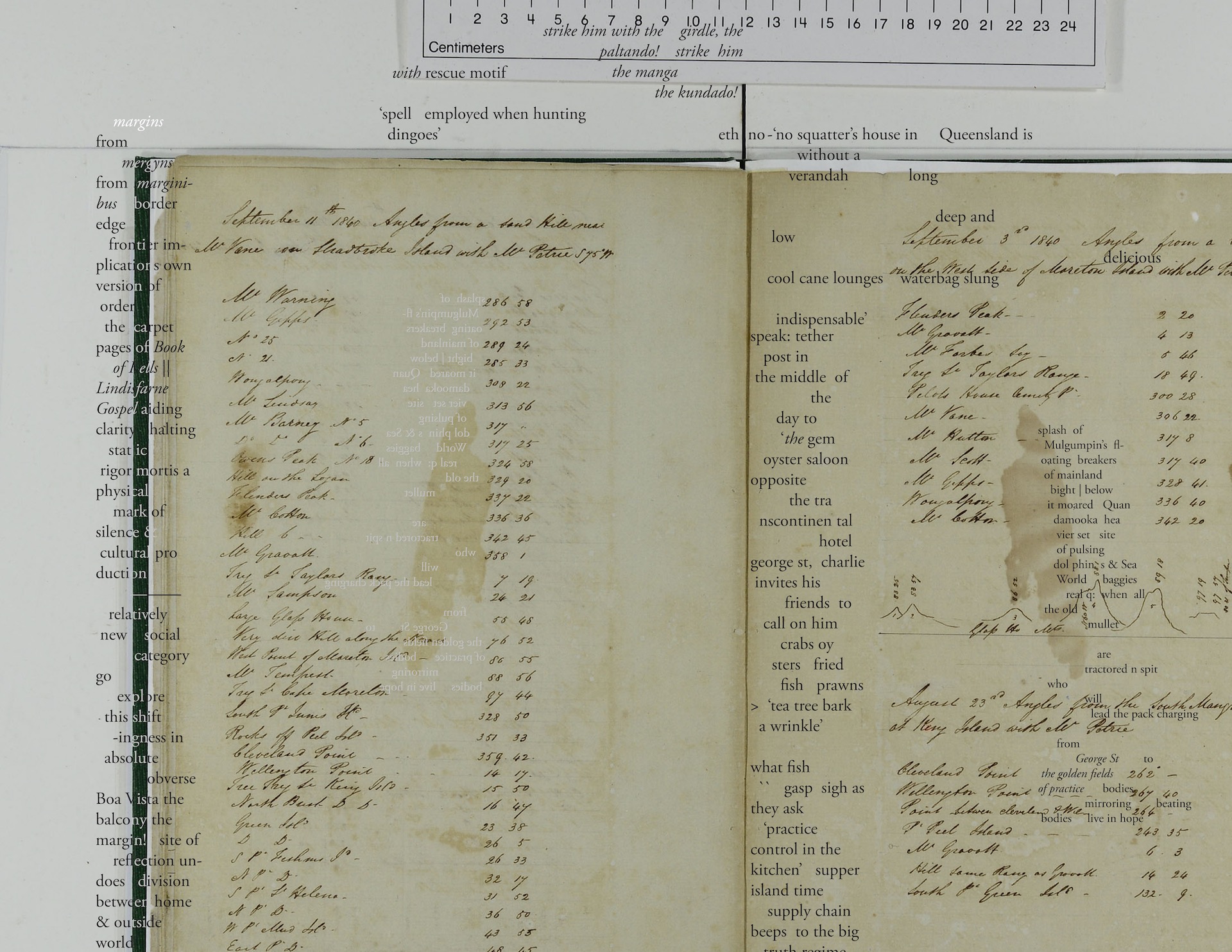

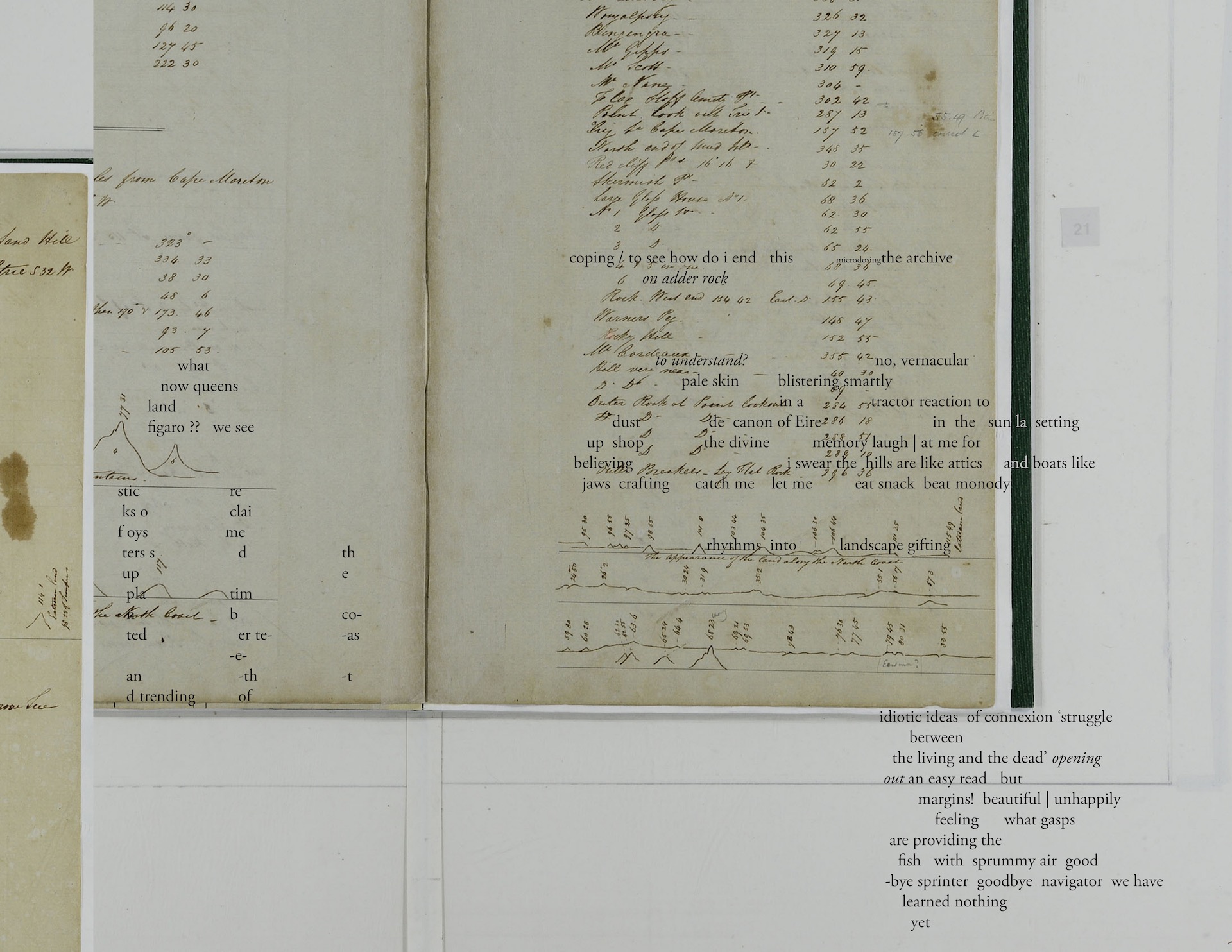

In a collage-based textual assemblage, Eva Phillips explores Moreton Bay’s culinary history against a backdrop provided by surveyor Robert Dixon. This feminist creative work references nineteenth-century Australian female poets, concepts of ethnographic verse, and settler and Indigenous poetics and visual art to play with ‘only absorption: made visible’ the shifting ideas of margins and marginalia. Who crafts the margins, who believe they live there, and what we can say for a more angled squint from the side-lines approach to research? Dixon’s hand has traced many landscapes along the east coast, and his time spent as surveyor in charge in the Moreton Bay district was coloured by acts of suspected mutiny and cartographical defiance—an appropriate theatrical backdrop to the convoluted text it bears.

‘The politics of food’ and ‘only absorption’ speak to each other through the past. These reflexive dialogues spring from one of our most basic needs—eating—and conjure a smorgasbord of colonial consumption; economic, political, and cultural. We hope readers engage with our work and detailed resource list in critical and creative ways.

We conducted this project on the unceded lands of the Jagera and Turrbal people. Funding was provided by Griffith University’s Arts, Education and Law summer scholars programme with the support of the Harry Gentle Resource Centre.

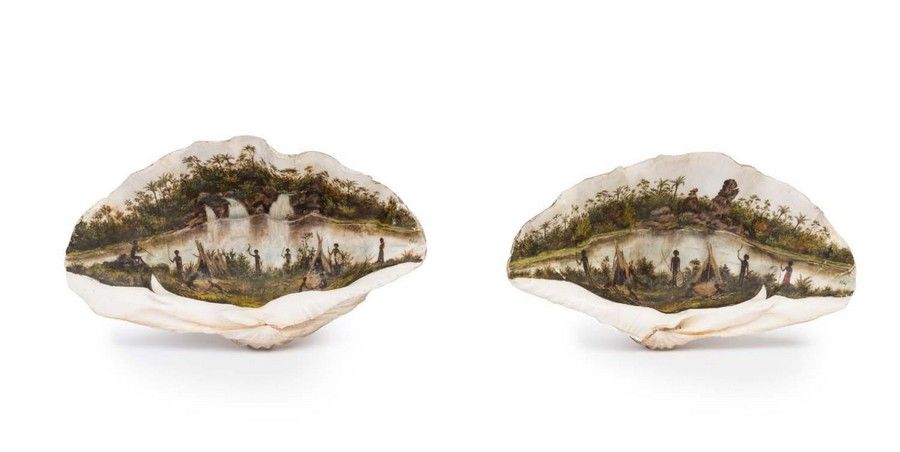

A curious piece of folk art painted by an unknown colonial artist came under the hammer in late 2020. Depicted on what appears to be a Black Lip Oyster, an Aboriginal man crouches or sits by a hut. Another subject nearby holds a spear and shield.

The artist’s observational and idyllic depiction of Indigenous lives and lifestyles is typical of many colonial paintings. Its peaceful riverine backdrop sits uneasily with the brutal realities of colonialism and dispossession.

Oyster or pearl shells were not an uncommon canvas for amateur artists in the nineteenth century. The pursuit was popular enough that the Queenslander provided instruction on the hobby for its readers in late 1899, with different techniques for watercolours and oils.

Other examples of contemporary shell art included decorative engravings, nautical scenes, and coats of arms. Those depicting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are an uncomfortable reminder of our colonial past.

Commercialising traditional seafood

Oyster shell art takes on greater significance, considering shellfish’s importance to First Nations diets and culture. Painted somewhere on the Burnett River on the central coast, the lush surrounds in image 1 belie the damage and disruption of commercial oyster farming to the Queensland coast and its estuaries.

Queensland’s colonial government first declared a commercial stake in oysters in the Fisheries Act 1878. It claimed fertile oyster grounds from the Tweed River to Gladstone, traditionally used by Aboriginal peoples for countless generations.

By the early 1920s, the government and oyster farmers recognised the estuaries and foreshores around Russell, Stradbroke, Moreton, Lamb, McLeay, and Coochiemudlo Island as ‘first-class oyster grounds’. The Wide Bay region, where our oyster was painted, was noted for ‘some of the river estuaries… producing excellent specimen for [oyster] maturing grounds’ (The Queenslander , 15 Jul 1922, 41).

State returns for 1919 show the scope and scale of the oyster industry. Eighty-five boats employed 108 men who worked 572 dredging leases and oyster bank licences in that year alone. An astonishing 14,880 bags of oysters had been hauled from Queensland’s waterways in the preceding 12 months (The Queenslander, 15 Jul 1922, 41).

Middens, cultural knowledge, and archaeology

Shell middens index the cultural importance of salt and freshwater shellfish to Indigenous people. They reveal crucial information about Indigenous campsites and food sources, shellfish species and biodiversity.

Australian archaeologists have studied middens since the nineteenth century. They commonly use radiocarbon dating to determine the age of a shell midden. It provides an age estimate with an error range by using samples of a shell to track its decomposition of carbon relative to the age of the shell.

Radiocarbon dating has its limits. Tides, humans, animals, and weather easily disturb middens, which are randomly structured over time, as well. Additional integration of carbon particles from external environmental sources can also skew results. The written historical record, and predominantly Indigenous oral histories, provides otherwise vital evidence to understand these sites and their significance.

Archaeological excavation of middens also reveals other cultural practices associated with food. In the mid-1970s, for instance, archeologists found clay tobacco pipes ‘in situ’ (within) two separate midden sites on the east coast of K’Gari (Fraser Island). Researchers suggest these pipes were deposited into the middens after the 1850s and may have been highly valued items integrated into traditional smoking practices (Courtney and McNiven, 1998: 51).

Reflexivity and resistance

The juxtaposition of ancient shell deposits and European artefacts potentially signals initial collaboration and exchange, an early interest in trade and the acquisition of ‘new’ and foreign products.

Seafood and fish formed a vital part of this nascent nineteenth-century economy (Ray Kerkhove, 2013: 144-56). In 1861, for instance, the Courier noted that, ‘Until very recently the inhabitants of Brisbane depended mostly for a supply of fish upon the aborigines of this locality [sic.].’ Four years later, Mr Bonney of the Melton Mowbray Hotel at Breakfast creek successfully spawned roe from five black trout he acquired from a local Aboriginal man (Brisbane Courier, 19 Jan 1865, 2).

As Europeans became increasingly familiar with local ecosystems and foods, which they so often gained from Indigenous inhabitants, Indigenous peoples became increasingly disadvantaged. The 1861 Brisbane Courier by-line, ‘TURNING THE TABLES’ , was an ominous portent of what was to come.

Resistance and reclamation

First Nations peoples resisted imposed colonial authority and control to maintain cultural identities. They kept alive cultural practices of preparing and sharing food despite missions, enforced removal and dislocation, replacing traditional diets with new foods like flour and sugar.

Middens also remained important Indigenous sites, even as dominant folk art forms like shell painting culturally appropriated traditional foodstuffs like oysters to depict idealised portrayals of Indigenous peoples and cultures.

Quandamooka artist Megan Cope’s recent art midden-like installation, RE FORMATION 2019, made from 12,000 pieces of cast concrete ilmenite, marks a critical intervention in this space. It highlights the scope and scale of oyster shells in First Nations’ histories, cultures, and communities, reclaiming the culturally appropriated canvas. Reframing the colonial lens, Cope invites us to consider critically the politics of food with fresh eyes (video interview 2020).

List of references

Primary Sources

‘A folk art painted pearl shell with Queensland Aboriginal scene, titled lower right ‘Burnett River, Queensland’, 20x19cm’. Lot 459, Sale 467 ‘Australian and Historical’, Leski Auctions. ©Leski Auctions. Reproduced with permission.

Campbell, Archibald James. ‘Oyster shell heap left by Aboriginal people, 1870.’ National Library of Australia.

‘Dugong Fishing c1890.’ State Library of Queensland, John Oxley Library Copy Print Collection. Not digitised.

Henderson, Dr H. W. B. ‘Tripcony Family Members on Con Tripcony’s Oyster Cutter “Nancy” in Moreton Bay ca 1889.’ Image P87024, Courtesy of Sunshine Coast Libraries.

A pair of rare and important hand-painted clam shells depicting North Queensland Aboriginal scenes, 19th century, monogrammed M.G. approximate size 17 x 27 cm each. © Mossgreen Auctions. HGRC has made all reasonable efforts to contact the copyright owner. Please contact us if you have further copyright information.

Newspapers

No title, Brisbane Courier, 19 Jan 1865, 2.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1267218

‘Home Decorations: SHELL PAINTING’, Queenslander, 25 Nov 1899, p. 1058.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article22562623

‘Local intelligence’, Courier 17 Aug 1861, 2.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4600551

Unicorn. ‘Science and Industry. The oyster industry: its origins and development,’ Queenslander, 15 Jul 1922, 41.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27433269

Secondary Sources

Buttrose, Ellie. ‘MEGAN COPE’S “RE FORMATION” TAKES THE OYSTER SHELL AS ITS SUBJECT,’ 8 Jan 2020. https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/megan-copes-reformation-takes-the-oyster-shell-as-its-subject-water/

Courtney, Kris and Ian McNive. ‘Clay Tobacco Pipes from Aboriginal Middens on Fraser Island, Queensland.’ Australian Archaeology 47, no. 1 (1998): 44-53.

Jones, Nicola. ‘Carbon dating, the archaeological workhorse, is getting a major reboot’, Nature, 19 May 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01499-y

Kerkhove, Ray. “Aboriginal Trade in Fish and Seafoods to Settlers in Nineteenth-Century South-East Queensland: A Vibrant Industry?” Queensland Review 20, no. 2 (2013): 144-56.

Marshall, Candice and Peter Scott. ‘Shell Midden provides insight into Indigenous life.’ ABC news; podcast Burleigh Heads: the Indigenous side, 1 Jun 2012. https://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2012/05/25/3515206.htm

Murgha, Letitia, ‘Indigenous Science: Shell middens and fish traps.’ Queensland Museum Network. https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2012/10/08/indigenous-science-shell-middens-and-fish-traps/

Redland City Council. ‘Quandamooka: Local history as recorded since European settlement.’ Redlands Coast Timelines, Redland Libraries.

https://www.redland.qld.gov.au/download/downloads/id/3982/quandamooka_timeline.pdf

In a collage-based textual assemblage, Eva Phillips explores Moreton Bay’s culinary history against a backdrop provided by surveyor Robert Dixon. This feminist creative work references nineteenth-century Australian female poets, concepts of ethnographic verse, and settler and Indigenous poetics and visual art to play with ‘only absorption: made visible’ the shifting ideas of margins and marginalia. Who crafts the margins, who believe they reside there, and what can be said for a more angled, squint from the side-lines approach to research? Dixon’s hand has traced many landscapes along the east coast, and his time spent as surveyor in charge in the Moreton Bay district was coloured by acts of suspected mutiny and cartographical defiance— an appropriate theatrical backdrop to the convoluted text it bears.

only absorption : made visible

Note: I have provided this readable, text-only version of only absorption : made visible for equity and access. The creative work is designed to be read as part of the collage where reading is deliberately difficult. The intentionally challenging text highlights the problems of accessing marginalised voices within the archives, and the heavy-handed ways in which many settlers have engaged with the Australian landscape. This text-only version has been rearranged in format but remains identical in content.

only absorption : made visible

kiss me on the lips for i love you,

land:

i am the backbone de subtropic

la lunchtime poem of this bay

i am text on text on te x t catch! me

oceanic, portable homeland &

monody to a body that is not mine

no, vernacular,

let me sit on the verandah, ‘liminal

space between the home and

the outside world’ let me, eat

snack beat rhythms into the

water and summon the fish! not me,

i am family of tractors on the

beach clotheshangered stingrays freed

at the last minute and navigator mullet

gasping for air b.t

(before tractor)

where were we : i in

the

poorhouse and you throwing

headstands on

some

unknown beach, doing

business with

the earth / late stages of plant

time her vegetal rhythm of unsynchronised

life! must learn to grow

again here we must

learn though

beware, ‘the patriotic gardener may,

from old associations, attempt the

rearing of his national fruits,

he will never succeed

in producing aught but curious abortions’

despairing, face the attitude of low

-energy cultivator, what more

can Moreton Bay Horti

cultural Society do but

lament those who say ‘what is the

good, of planting trees

when we may never live

to enjoy . . .

this is a feeling, unhappily

so common in

this age, as almost to be termed its distinctive character

every thing we do is to be done

for ourselves,

nothing for posterity apres

moi le deluge —

is the motto

of the utilitarians of the nineteenth <

century’

fall apart, farmers! as you did done shocked

by the

possibilities of indulging in new

feast opportunities : who

tells you what to eat, landscape gifting

receipts of roasting possum, stock

pots of wallaby ways away, plant

time,

‘the social consequences of the Price

Revolution are revealed by these charts’ we

have felt hunger prior, bad harvests and

dinners of acorns, bark ‘the multitudes

weeping and

wailing’ pragmatism stirring in starving

bellies we turn to, ~

{caretaker }~ the riots of starvation &

naughty capitalism begun,

and thus named after maters

who, carrying the

bodies of their dead children in the

streets, dropped

fever on

grain prices and schlepped

seeds in their skirts count on your

fingers, an idea: the seasons

of sprinter

and sprummer modernist

reaction to ancient blooms we have no rhythm

here, but living is key the food of

the table also the food of the

sea adjust

lens, / cook to [p] discover how and

why we the body, land the body, can never quite be

me sand | you sand

sand sand chew spit! see the sp lit in the middle of the page

boundary built gallery,

rooms we make an idea: museum

in the garden, no need

to bring the work inside busy curators spit to tell

we develop

things of the spirit that require us

to keep our distance from the ground

goodbye sprinter! goodbye

sprummer! we do not need

your growing patterns here we have

instead, horror, and it

has a face, bodies mirroring

bodies mirroring movement in the captures

light snaps^ of figures ‘large

and vigorous, due to their varied diet’ island

food, Foley lives

in ‘hope that my heroine could be your heroine,

as she defies all odds with an unspoken

eloquence of spunk’ these words for me? no,

elsewhere

: a different sideline the others

sit, newer

members of this truth regime the archive, we

are collecting

life, wading through

~~ ~ ~ a lifting tale that

hangs breakers like gifts

on the walls taut with misery these

new sideliners reached

for

empathy in the wrong shadows do not align

do not align

my

strug

gle wi th

theirs! mine the trouble of boat

rides dead

mothers’ pale skin

blistering in the sun; famished

in love

land &

the dust consigning

as power, we

collect

stories of how these farmers

were

burdened with true disease,

ignorance brought over in ships, a cross

-pollination ‘whereby

forms of repression

developed in the

Old World were transported

to the New’

how many sidelines to

an infinite shape,

the nexus

swelling and fantastic in scale

full of natural

devastation see ea,

coloniser vs

colonised grand

stadium games, wherein the side

that builds small toothy enclosures

for swimming in the bay are

perhaps the ones most out of

their

depth : l l t

i i i

n & n of m

e e b

s s e

r

in the water, soft barricade against

becoming

breakfast we make witches of anything

nurse sharks new people whole cont

inents, for now, turn

to the place of

these timber teeth

in the sea

weary dentin exposed and nervous 2

St Helena

Island

and its surrounds (island)

( isl)

(and)

( isl)

(and). (and-isl)

(and-isl)

360antipodeanism

causing

‘no domestication

or salvation,

only threat of

absorption’

‘we need to go where the archive

cannot’ for John Kean that

means tracking rain making

among the

painters of Haasts Bluff,

Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula

making

lightning, ibis | warrpanji (kan

garoo rat) | lightning,

ibis

how do we find

similar ilk

when the directive is

to shoot

straight for the ‘arch (arkh- arkhi, first,

chief |primeval)’ -ives been thinking

about deep water, just

like she and, like she,

bored of men, toppled

and buckled by difference and exhaustion they

/ she | | old

me are then

taken with romantic notion——

Julie Gough, touching archive ‘holding

them

clarified if they felt right

in the hand

what type of stone— could i

have made this, did an

ancestor’

i can’t help! bringing in other areas

we, not Haasts Bluff we, not

Ho bart

we still, riddled with bugs huge

pictures singing with

sand ‘sable sons of the soil’ driven

from the field as Mr Walker has

begun ‘hauling

his seine’ in the waters

of

…… bugs, back the

Bay ey up the citation list of what, ‘do those hackademics, anthros, researchers

activists want for nothing

__________ ?’ a significant life, read

site specific

bites on this land of wooden shark net /

Bonita Ely’s Murray

River circles

tiny redux

instances

of we | the entrapment of

land

time to eat, clean, ‘they brought

us fish, for which

we gave them potatoes’ | standing at doorways

with sugarbags until the oil lamps were lit

and a chasing was

begun over Breakfast Creek

love land,

powerful numbers at the bottom of

the page r

i

c

e (but written more tilted) —

lbs

42 , 9(or seven) ½ / 16

“

ditto ditto x 4

42

“

ditto x 14

84 9 ½ /16

stocktake a beautiful thing tell me how much

rice is eaten in a month in

the Bay (1833) but gridlines ! why are you making

me cry

in Naarm nite tell me

of ‘take this

for it

is

my

bo dy’ (sj N, n.d) scones

full of Wiradjuri

blood & test for

cyclical batch of

six ::: around the table an idea:

do you eat

the Bathurst

genome shoulder the belly of

death

or decline taste, in good &

waste

> the flour >>>>>>> “ironbark” “

over-

landing” Jim

apostrophizeth his qondam

mate — a ballad

of qld

‘teeth like

a

Moreton

Bay shark’ ‘in the

gunyah down there

by the lake; [t]he grubs

that she

gathered, the

lizards she

stewed

the damper

you taught

her

to bake’. trike him with the

girdle, the

paltando! strike him

the manga

the kundado!

with rescue motif

‘spell employed when hunting

dingoes’ eth no -‘no squatter’s

house in Queensland is

without a

verandah long

deep and

low delicious

cool cane

lounges waterbag slung

indispensable’

speak: tether

post in

the middle of

the

day to

‘the gem

oyster saloon opposite

the tra

nscontinen tal

hotel george st, charlie

invites his

friends to

call on him

crabs oy

sters fried

fish prawns

> ‘tea tree bark

a wrinkle’

what fish

“ gasp sigh as they ask

‘practice control in the kitchen’ supper

island time

supply chain beeps to the big

truth regime splash of

Mulgumpin’s fl-

-oating breakers

of mainland

bight | below

it moared Quan

damooka hea

vier set site

of pulsing

dol phins & Sea

World baggies

real q: when all

the old

mullet

are

tractored n spit

who

will

lead the pack charging

from

George St to

the golden fields

of practice bodies

mirroring beating

bodies beached

live on in hope

*

margins from

mergyns from marginibus

border edge

frontier implications own

version of

order

the carpet

pages of Book

of Kells || Lindisfarne

Gospel aiding clarity halting

stat ic

rigor mortis a

physical

mark of silence &

cultural pro duction

———

relatively

new social

category go

explore

this shift

-ingness in

absolute

obverse

Boa Vista the

balcony the margin! site of

reflection undoes

division between home

& outside world

*

what

now queens

land

figaro ?? we see

stic re

ks o clai

f oys me

ters s d th

up e

pla tim

n b co-

ted er te- -as

-e-

an -th -t

d trending of

coping / to see how do i end this microdosingthe archive

on adder rock

to understand? no, vernacular

pale skin blistering smartly

in a tractor reaction to

dust de canon of Eire

in the sun la setting

up shop the divine memory

laugh | at me for

believing i swear the hills are like

attics and boats like

jaws crafting catch me let me eat

snack beat monody

rhythms into landscape gifting

idiotic ideas of connexion ‘struggle

between

the living and the dead’ opening

out an easy read but

margins! beautiful | unhappily

feeling what gasps

are providing the

fish with sprummy air good

-bye sprinter goodbye navigator we have

learned nothing

yet

Resource List

Note: An asterisk (*) shows sources quoted or adapted in the piece ‘only absorption: made visible.’ A caret (^) indicates sources used for research in ‘The politics of food.’

Secondary Sources

*Addison, Susan and McKay, Judith. A Good Plain Cook: An Edible History of Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Museum, 1985.

*Bellear, Lisa. Aboriginal Country. Crawley: University of Western Australia Publishing, 2018.

Blyton, G. ‘Harry Brown (c. 1819-1854): Contribution of an Aboriginal Guide in Australian Exploration.’ Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 63-82.

Brass, Tom. ‘Contextualizing Sugar Production in Nineteenth-Century Queensland.’ Slavery and Abolition 15, no. 1 (1994): 100-17.

^ Buttrose, Ellie, ‘MEGAN COPE’S ‘RE FORMATION’ TAKES THE OYSTER SHELL AS ITS SUBJECT’, 8 Jan 2020. https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/megan-copes-reformation-takes-the-oyster-shell-as-its-subject-water/.

Cahir F., Schlagloth R., & Clark, Ian D. ‘The Importance of the Koala in Aboriginal Society in Nineteenth-Century Queensland (Australia): A Reconsideration of the Archival Record.’ Anthrozoos 35, no. 1 (2022): 75-89.

^ Courtney, Kris and McNiven, Ian. ‘Clay Tobacco Pipes from Aboriginal Middens on Fraser Island, Queensland’, Australian Archaeology 47, no. 1 (1998): 44-53.

https://www.academia.edu/42933700/Clay_Tobacco_Pipes_from_Aboriginal_Middens_on_Fraser_Island.

Evans, Julie Grimshaw, Patricia and Standish, Ann ‘Caring for Country: Yuwalaraay Women and Attachments to Land on an Australian Colonial Frontier.’ Journal of Women’s History 14, no. 4. (2003): 15-37.

*Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

Forge, C. ‘The Hidden History of Aboriginal Stockwoman.’ Museums Victoria, (2020). https://museumsvictoria.com.au/article/the-hidden-history-of-aboriginal-stockwoman/.

*Jorgensen, D, and Ian McLean, eds. Indigenous Archives: The Making and Unmaking of Aboriginal Art. Crawley: University of Western Australia Scholarly Publishing, 2017.

^Jones, Nicola. ‘Carbon dating, the archaeological workhorse, is getting a major reboot.’ Nature, 19 May 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01499-y.

^*Kerkhove, Ray. ‘Aboriginal Trade in Fish and Seafoods to Settlers in Nineteenth-Century South-East Queensland: A Vibrant Industry?’. Queensland Review 20, no. 2 (2013): 144-56.

Kerkhove, Ray. ‘Indigenous Aboriginal Sites of Southside Brisbane.’ Mapping Brisbane History, 2014. https://mappingbrisbanehistory.com.au/brisbane-history-essays/brisbane-southside-history/first-australians-and-original-landscape/indigenous-sites/.

Kerkhove, Ray. ‘Aboriginal Camps as Urban Foundations? Evidence from Southern Queensland.’ Aboriginal History 42. (2018): 141-72.

*Keys, Cathy. ‘Sharing the Waterways: Shark-Proof Swimming, Penal Detention and the Early History of St Helena Island, Moreton Bay.’ Queensland Review 27, no. 2 (2020): 121-36.

Krichnauff, Skye. ‘A Boomerang, Porridge in the Pocket and Other Stories of “the Blacks’ Camp”.’ Journal of Australian Studies 43, no. 3. (2019): 299–316.

Larner, S. ‘Bountiful Bunyas: A Charismatic Tree with a Fascinating History.’ State Library of Queensland, (2021). https://www.slq.qld.gov.au/blog/bountiful-bunyas-charismatic-tree-fascinating-history.

^Marshall, Candice and Scott, Peter. ABC News Shell Midden provides insight into Indigenous life; podcast Burleigh Heads: the indigenous side, 1 June 2012.

https://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2012/05/25/3515206.htm.

Morrison, M., McNaughton D. and Keating, C. ‘“Their God Is Their Belly”: Moravian Missionaries at the Weipa Mission (1898–1932), Cape York Peninsula.’ Archaeology in Oceania 50, no. 2. (2015): 85-104.

^Murgha, Letitia. ‘Indigenous Science: Shell middens and fish traps’, Queensland Museum network (2012). https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2012/10/08/indigenous-science-shell-middens-and-fish-traps/.

Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Newling, J. and Hill, S. ‘Curry Stuff.’ Sydney Living Museums (2017). https://blogs.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/cook/curry-stuff/.

*Norman, S. J. 2010-2019 ongoing. Take this, for it is my body. Performance piece. https://www.sarahjanenorman.com/take-this-for-it-is-my-body.

*O’Leary, John. ‘“The Life, the Loves, of That Dark Race”: The Ethnographic Verse of Mid-Nineteenth-Century Australia.’ Australian Literary Studies 23, no. 1 (April 2007): 3-17.

*Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge, 1993.

*Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of National Parks, Sport and Racing. ‘Artificial Reefs Locality Map, Moreton Bay Marine Park.’ Queensland Government, August 2015. https://parks.des.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/166904/artificial-reefs-locality-map.pdf.

^ Redland City Council. ‘Quandamooka: Local history as recorded since European settlement.’ Redlands Coast Timelines, Redland Libraries.

https://www.redland.qld.gov.au/download/downloads/id/3982/quandamooka_timeline.pdf.

Rentoul, Archie. Island of a Million Tears: History of Dunwich Benevolent Asylum 1866-1946. Inspire Publishing, 2015.

*Ryan, John Charles. Plants in Contemporary Poetry. 1 ed.: Routledge, 2017.

Sanderson, R. ‘Many Beautiful Things: Colonial Botanists’ Accounts of the North Queensland Rainforests.’ Historical Records of Australian Science 18 (2007): 1-18.

Santich, Barbara. ‘Nineteenth-Century Experimentation and the Role of Indigenous Foods in Australian Food Culture.’ Australian Humanities Review 51, no. 1 (November 2011): NA.

Singley, Blake. ‘Parrot Pie and Possum Curry—how Colonial Australians Embraced Native food,’ (26 Jan 2017). https://theconversation.com/parrot-pie-and-possum-curry-how-colonial-australians-embraced-native-food-59977.

Steffens M., Jamieson L. and Kapellas, K. ‘Historical Factors, Discrimination and Oral Health among Aboriginal Australians.’ Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Undeserved 27, no. 1. (2016): 30-45.

*Stewart, Douglas, and Keesing, Nancy (eds). Australian Bush Ballads. Australian Classics. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson, 1955.

*Symons, Michael. One Continuous Picnic: A History of Eating in Australia. Adelaide: Duck Press, 1982.

*Tyquiengco, Marina. ‘Source to Subject: Fiona Foley’s Evolving Use of Archives.’ Genealogy 4, no. 3 (2020).

*Vickery, Ann. ‘A ‘Lonely Crossing’: Approaching Nineteenth-Century Australian Women’s Poetry.’ Victorian Poetry 40, Spring, no. 1 (2002): 33-54.

White, Jessica. ‘“The Most Formidable Teeth”: Gardening, Collecting, and Violence in Nineteenth Century South-Western Australia.’ Tamkang Review 51, no. 1 (2020): 85-108.

Woodcock, Shannon. ‘Biting the Hand That Feeds: Australian Cuisine and Aboriginal Sovereignty in the Great Sandy Strait.’ Feminist Review 1, no. 114. (2016): 33-47. https://www.academia.edu/31146264/biting_the_hand_that_feeds_Australian_cuisine_and_Aboriginal_sovereignty_in_the_Great_Sandy_Strait.

Primary Sources

Archival

*QSA Item number ITM291083, Dixon, Robert. Moreton Bay Trigonometrical Survey – Angles and Sketches at Moreton Bay, Surveyor Dixon 24 May 1840 – 11 September 1840. https://www.archivessearch.qld.gov.au/items/ITM291083.

Ravenstein, F. ‘General Map of Australia and Tasmania or Van Diemen’s Land.’ Edinburgh: A. & C. Black, 1857. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229935087.

Photographic

^A folk art painted pearl shell with Queensland Aboriginal scene, titled lower right ‘Burnett River, Queensland, 20x19cm.’ Lot 459, Sale 467 ‘Australian and Historical’, Leski Auctions. ©Leski Auctions.

https://auctions.leski.com.au/lot-details/index/catalog/551/lot/170630/A-folk-art-painted-pearl-shell-with-Queensland-Aboriginal-scene-titled-lower-right-Burnett-River-Queensland-19th-century-20-x-19cm.

^Dr H. W. B. Henderson, Tripcony Family Members on Con Tripcony’s Oyster Cutter “Nancy” in Moreton Bay ca 1889. Image Number P87024, Sunshine Coast Libraries.

^ Dugong fishermen huts at Amity Point on Stradbroke Island, 1891. State Library of Queensland, Negative Number 165983.

https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/229337.

^Campbell, Archibald James. Oyster shell heap left by Aboriginal people, 1870. National Library of Australia.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147128324.

^Megan Cope with her Artwork ‘RE FORMATION 2019’ at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/megan-copes-reformation-takes-the-oyster-shell-as-its-subject-water/.

^A pair of rare and important hand-painted clam shells depicting North Queensland Aboriginal scenes, 19th century, monogrammed M.G. approximate size 17 x 27 cm each. © Mossgreen Auctions.

https://www.carters.com.au/index.cfm/index/11888-sea-shells-engraved-painted-and-carved/.

^ Aboriginal Australians at Meal Time in the Bloomfield River District. State Library of Queensland Digital Library: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, 1885. https://digital.slq.qld.gov.au/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2656030.

Newspapers

Robinson, T and Wade, H. ‘Sketches of Life in Queensland.’ Trove, 1884.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136344526.

Roth, W. E. ‘Ethnology – Aboriginal Food Vi.’ The Queenslander (Brisbane), 11 Jan 1902, p.58. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/21619567/2519247.

^Unicorn. ‘The Oyster Industry: Its Origin and Development’ The Queenslander (Brisbane), 15 July 1922, 41. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/27433269.

W. T. ‘The Sketcher.’ The Queenslander (Brisbane), 1886.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19805787.

‘An Aboriginal Mission.’ Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth), 1881. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/199461301.

‘Aboriginal Superstitions.’ Geraldton Murchison Telegraph, 1896.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article260157200.

‘By Wire.’ The Week (Brisbane), 1887, 2. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/182627049/20952654.

^’Home Decorations: Shell Painting’. The Queenslander (Brisbane), 25 Nov 1889,

1058. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/22562623.

^’Local intelligence’, Courier 17 Aug 1861, 2.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4600551.

^ No title, Brisbane Courier, 19 Jan 1865, 2.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1267218.

‘Queensland Aboriginals.’ Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser 1895.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article146912017.

‘Queensland. Food-Yielding Trees.’ Advocate, 1887.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article170598254.

‘Royal Society of Queensland. Aboriginal, Fish Poison.’ The Queenslander, 1895.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21636897.

‘Queensland Aboriginal Missions.’ The Brisbane Courier (Brisbane), 13 Nov 1915, p. 7.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20092052.

*Moreton Bay Horticultural Society. ‘Agricultural Resources of Moreton Bay.’ The People’s Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 2 April 1853.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article251541368.