About the project

Drawing the Downs: The life and art of Thomas John Domville Taylor

English-born Thomas John Domville Taylor arrived on the Darling Downs by 1842, making him one of the earliest European settlers in the region. While living and working on his property Tummaville, Taylor kept a visual record of the world around him in the form of pencil sketches. Today, these sketches provide some of the earliest insights into life on the Downs. This presentation, delivered to members of The Royal Historical Society of Queensland on 9 December 2020, biographs Taylor’s life with particular attention to the years he spent on the Darling Downs c.1842-46, especially Taylor’s life on Tummaville station, racial tensions and conflict’s during Taylor’s residence in the region, and Taylor’s participation in the 1845 expedition led by Christopher Pemberton Hodgson in search of explorer Ludwig Leichhardt

About the author

Timothy Roberts is a professional art historian specialising in Australian art heritage, decorative arts and material culture before 1945. He is a member and past President of Professional Historians Association (Qld) Inc., and a former Councillor of The Royal Historical Society of Queensland. In 2019 he was appointed a Visiting Fellow of the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, Griffith University, to research artistic impressions made in or inspired by the geographical region that would become Queensland in 1859.

During his time as a Visiting Fellow at the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, Tim has given talks at the Queensland State Archives and the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. His biography on Thomas John Domville Taylor can be accessed here.

Please note: some content in this text may be distressing for some readers.

On coming to a gully which seemed to go thro’ an opening between the scrub, we followed it down which brought us to a creek in a beautiful valley on which we camped; at finding a small water hole with tea trees lining it near which one solitary cockatoo was perched on a high gum tree, from this circumstance we called the creek Cockatoo Creek. The creek was bounded by beautiful sound flats, skirted by open undulating ridges and well adapted for a sheep. It was quite a relief to our eyes after the sandy scrubby country we had travelled over.

Thomas John Domville Taylor, 6 September 1845

Thomas John Domville Taylor’s relationship with Queensland’s formative pastoral landscape is unique. Born into a landed family in England and travelling to Australia in his early 20’s, Taylor assumed the roles of pastoralist and later explorer in the six years that he spent living and working on the Darling Downs. While in Australia, Taylor sketched his surrounds, and kept a pragmatic account of his participation in Christopher Pemberton Hodgson’s search expedition for Ludwig Leichhardt in August-September 1845. Six sketches by Taylor were collected by the National Library of Australia in 2010; this was later augmented by the Library’s acquisition of more sketches, a scrapbook and a journal by Taylor in 2017.

Taylor was the third child of Mascie Domvile Taylor and his wife Diana née Houghton. He was baptised on 10 April 1817 in Chester Cathedral. Taylor’s father had matriculated from Brasenose College, Oxford in 1802 and attained a Master of Arts in 1809. He was appointed Rector of Langton, Yorkshire in 1818 and Moreton Corbett, Shropshire the following year, a post he held until his death on 9 October 1845. [1] Macsie Domville Taylor held the Manorial seat of Lymm Hall; is it likely that Thomas and his siblings grew up there. The Taylors were socially connected; Thomas John Domville Taylor’s godfather was Lord Amesbury. [2]

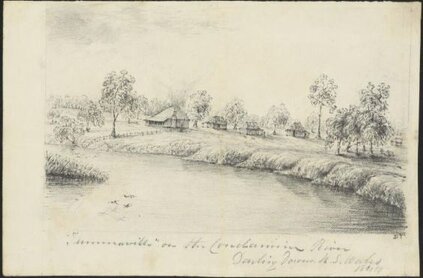

Taylor arrived in Sydney aboard the Euphrates on 20 December 1839. [3] Little is known of his early time in Australia, however Taylor’s sketchbooks reveal that he travelled south to Omeo Plains and the Snowy Mountains before moving northward passing Liverpool Plains and Byron Plains, eventually reaching Queensland in 1841, accompanied by John Howell and Charles Markham. [4] By 1842 Taylor had established himself on a pastoral lease bordering the Condamine River known as the Broadwater. Taylor was partnered with Dr John Rolland, who had travelled to the Downs with his wife Fanny and their two children in 1842. [5] The lease for Broadwater had initially been taken up by James Wingate in 1841, but was renamed Tummaville by Rolland and Taylor by 1843. [6] Stations neighbouring Tummaville included Yandilla, licensed to St George Richard Gore, and Ellangowan, licensed to John Thane, with Cecil Plains and Eton Vale stations nearby.

- Joseph Foster, ed., Alumni Oronienses: the members of the University of Oxford 1715-1886: their parentage, birthplace and year of birth, with a record of their degrees, vol. 4, Oxford: Parker & Co., (c.1891), p. 1395.

- Flintshire Observer, Mining Journal and General Advertiser for the Counties of Flint and Denbigh, 21 September 1889, p. 6.

- ‘Shipping Intelligence’, The Australian, 21 December 1839, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36860100.

- SLQ, Colonial Secretary’s letters received relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland 1822-1860, A2 series, reel 11, CF Ref. No. 41/00114, Letter from Domville Taylor to the Colonial Secretary, 4 January 1841, requesting access to Moreton Bay settlement. https://content.slq.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/0005-198221-slq-a2-series-reel-a2.11-2014-09.pdf.

- ‘Departure’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 1842, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12423403.

- New South Wales Government Gazette, 27 October 1843 (no. 90), p. 1395.

Tummaville was established during a wave of pastoral growth to the west of Toowoomba during the early 1840s. One commentator noted in November 1841 ‘I believe there is no doubt that all the stations on Darling Downs have been taken up. Parties who now want runs “go over” the range to the Moreton Bay side.’ [7] As early arrivals in the region, Rolland and Taylor essentially built Tummaville from the ground up. Taylor’s sketch of the first camp at Tummaville shows a Spartan set up of a circular tent and two gunyah-style constructions around a campfire; with a dray, a few head of cattle, chickens, a dog and a horse accompanying the party. A second sketch showing the finished station evidences that within a couple of years the business partners had erected four more substantial structures, including a large building with verandah and fireplace. Dr Rolland provided medical services to the community around him, and in October 1843 Fanny Rolland gave birth to the couple’s third child, Charlotte, the first baby to be born in the region.

Life on this rural frontier was challenging. As Rolland was the only trained medical practitioner in the region, he attended to nearby emergencies, including the fatality of John Hill, who had been speared at Eton Vale station. Christopher Gorry, an employee at Eton Vale, described the event:

John Hill started early one morning for the camp near Mt. Rascal, in order to take home some bullocks. He told me to follow him in about half an hour’s time, which I did, and to my surprise, met poor John Hill with a spear right between his shoulders, sticking to the saddle while his horse galloped home, and the spear dangling at the horse’ rump, until he arrived at the slip-rail near the house with myself close after him. Mr. Elliott, with myself and others, came to his relief. We lifted poor John off the horse, and had to cut vest and shirt on each side of the spear wound ere we could take it from the wound in his body, four or five inches. He lived in great pain. I was send for Dr. Rolland at his Broadwater station, who attended John for a week, but held out no hope of his recovery. He lingered on for eighteen days, and then passed away. Another station hand any myself attended to his requirements up to the time of his death. In those days there were no coffins at hand, so we made a shroud of his blanket, and buried his body in a sheet of bark, in a little flat near the garden on the bank of the creek. [8]

Another tragedy occurred in 1843 when a man died trying to swim across the Condamine River. After two weeks his body was found and interred at Tummaville. [9]

While living at Tummaville, Taylor made several sketches of the station and its surrounds, as well as depictions of daily life. These sketches include a panorama of the Long Reach in the Broadwater at Tummaville, a detailed view of the landscape around Cecil Plains station, and a sketch of a bullock dray descending Cunningham’s Gap. A second, more comical sketch titled Gee Smiler! highlights the difficulty of traversing the range between the commercial centres around Moreton Bay and the pastoral leases on the Downs. More prosaic scenes depicting roping a bullock, roping cattle, and a wool press are also represented among Taylor’s drawings.

7. ‘Peels River’, The Omnibus and Sydney Spectator, 27 November 1841, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228064526.

8. Thomas Hall, The Early History of Warwick District and Pioneers of the Darling Downs, Toowoomba: Robertson & Provan, Ltd, 1925, p. 21.

9. ‘Moreton Bay’, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 September 1843, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12413308.

Please note: some content in this text may be distressing for some readers.

As settlers began to select and divide indigenous Australian country, they disrupted passage through country and obstructed access to sacred sites. This caused relationships between local indigenous communities on the Darling Downs, among them the Baruŋgam, Geynyon, Jarowair and Giabal people, and new pastoral occupiers to rapidly disintegrate. The earlier mentioned account by Christopher Gorry of John Hill’s demise was not an isolated incident; writing to the editor of the Sydney Gazette in August 1842, “Squatting” called for additional border police to be deployed in the Darling Downs region following an increase in resistance hostility by local indigenous communities, resulting in death and injury to settlers and livestock. [10] Taylor was personally connected to at least two conflicts, the first occurring in late 1842 when an aggressing party consisting of Ralph Gore, Sydenham Russell, and Taylor attacked an indigenous community who were passing through lands occupied by Tummaville and Yandilla stations. Writing about the incident in 1887, Henry Stuart Russell recalled:

The blacks had been more aggressive of late than ever. They were harrying and killing cattle wherever cattle were. The shepherds were in a terrible state of “funk,” and no wonder. My brother had caught them, when crossing the plain between Yandilla and Tummavil [sic] in company with Ralph Gore and Taylor, coolly rounding a mob up in the open, and preparing to kill. A “set-to” was the consequence. The blacks numbered about three hundred, and kept admirable order and showed unusual courage. Upon the firing of a shot, the “ducking” of heads and rush on their assailants were instantaneous, well arranged, and executed. Syd’s horse was fidgetty; [sic] so he jumped off and let him loose. The “brummagem” double barrelled gun which he had—mine, however—burst in his hands without doing damage ; and it must have been quite half-an-hour before the mob, which showed a steady line throughout, had retreated, step by step, to the timber which skirted the western edge of the plain, and only then turned tail. [11]

A second incident occurred in mid-1844, when reports emerged of hostile action by an indigenous group west of Ipswich. A dray belonging to the Forbes Brothers was halted and robbed; a short while later an attempt to rob a dray belonging to Rolland and Taylor passing the same route was unsuccessful. [12]

It is unknown how frequently Taylor and his companions at Tummaville conflicted with indigenous communities, however Taylor visually recorded growing tensions between the indigenous residents and the occupying pastoralists in the form of graphic sketches. One such drawing executed in 1843 records 11 men loading their rifles and shooting as they advance toward a group of about 25 indigenous men, women and infants. The presence of gunyahs in the image suggests that the aggressors may have approached a camp, which justifies the lack of defence observed in the scene – just one man peers around a tree holding two spears, and another man carries a boomerang. Taylor inscribed beneath the image ‘The Blacks who robbed the drays on the Main Range of Mountains attacked by a party of Darling Downs Squatters after following them for a week.’ Historian Ray Kerkhove notes that this image may be connected to the storming of the Rosewood Scrub in late-1843. [13] The image is one of the earliest and most significant depictions of violence by European communities on the Darling Downs towards indigenous people.

Several drawings in Taylor’s sketchbook reiterate the constant vigilance by members on both sides of the conflict. Aborigines of Australia on the lookout for whitefellows depicts five indigenous people sitting atop an elevated viewpoint observing three men on horseback emerging from scrub in the distance. Fine details including scarring on the men suggest that Taylor may have based this representation on indigenous subjects that he had contact with. Squatters in search of blacks N.S.Wales depicts a dozen relaxed squatters at camp with their horses and travelling accoutrement. This image contrasts with a more potent scene a few pages later, A party in search of blacks, which depicts a man holding a rifle giving directions to four similarly dressed and armed man, while an attendant, possibly indigenous, sits nearby, and a large group of figures on horseback amass in the middle ground. Towards the end of the sketchbook, one page titled Shooting blacks N.S.Wales features three loose drafts of armed settlers aggressing towards indigenous Australians, and another titled Drinking N.S.Wales depicts an indigenous man armed with a spear, about to attack a settler who is drinking from a waterhole.

These sketches contrast with more intimate depictions of indigenous subjects in Taylor’s papers. A caricature portrait of Peter Boombiburra in the scrapbook of Taylor’s step-mother depicts Taylor’s ‘servant’ dressed in trousers, smoking a pipe. His scarring is visible and a camp dog sits by his side. A remarkable and fine portrait of a boy from Moreton Bay named Jimmy or Timmy, possibly not by Taylor’s hand, is held among his drawings. Within Taylor’s sketchbook are two depictions of indigenous subjects related to Thomas Livingstone Mitchell’s Journal of an Expedition into the Interior of Tropical Australia: in search of a route from Sydney to the Gulf of Carpentaria, published in 1848. Taylor’s most intimate and impressive drawing of indigenous life was executed in 1844, and depicts a group of men performing a corroboree around a campfire by moonlight, accompanied by women instrumentalists. To date no letters or diaries by Taylor have come to light to reveal further details about his relationships with the local indigenous community while living at Tummaville.

Despite Taylor’s depictions of both sides of the conflict that was growing on the Downs, it cannot be said that he was a passive observer. In addition to the conflicts that Taylor participated in during his time at Tummaville, while taking part in a search expedition for explorer Ludwig Leichhardt led by Christopher Pemberton Hodgson, Taylor kept a detailed diary that reveal his views towards indigenous Australian people. Most of Taylor’s observations of indigenous Australians in his diary are neutral in tone and describe the interactions that he had, however one week into the expedition, Taylor reveals his own fear for Dr Leichhardt’s fate:

It was certainly a queer plan for a man to encamp for 10 days in within less than 50 yards of a dense scrub that was at the time occupied by the blacks and we could not help fearing that Dr. Leichardt [sic] put more faith in the friendly appearance and demonstrations of the blacks than they are generally known to possess. [14]

This comment is likely informed by Taylor’s experiences with conflict during his time at Tummaville. It is observed though, that once Taylor was familiar with a community, his reaction was much warmer. On 5 September during the party’s return from their search, Taylor wrote:

Hearing a cooing behind us, on looking back perceived some blacks running after us; we halted and had a talk with them. They would not allow us to approach on horseback evidently afraid of the horses. They were some of our old friends we saw at Euröonbah. They pointed out the place Dr.Leichardt [sic] crossed the Range, the direction of Banandown they did not know. To the Eastward they said were very high mountains. Johnny presented them with an old shirt. [15]

10. ‘Original Correspondence’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 27 August 1842, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2557221.

11. Henry Stuart Russell, The Genesis of Queensland: an account of the first exploring journeys to and over the Darling Downs: the earliest days of their occupation; social life; station seeking; the course of discovery, northwards and westward; and a resume of the causes which led to the reparation from New South Wales, Sydney: Turner & Henderson, 1888, p. 328. https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1305181h.html.

12. ‘News From The Interior’, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 August 1844, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12413468.

13. For further discussion on the Battle of One Tree Hill, please consult Ray Kerkhove, Mapping Frontier Conflict in south-east Queensland, 2017, Harry Gentle Resource Centre.

14. Thomas John Domville Taylor, Journal of the expedition in search of Leichhardt, 1845 [Manuscript]. National Library of Australia PIC MSR 14/1/6 Volume 1190 #PIC/20229/1-2

15. Ibid.

In July 1844 Rolland and Taylor dissolved their business partnership. Taylor negotiated a new partnership for Tummaville with a member of the Ross family. This venture was short-lived; within a year Taylor left Tummaville to take part in an expedition mounted by Christopher Pemberton Hodgson to search for explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. A search party consisting of Hodgson, Taylor, James Rogers, Frederick Isaac, William Calvert, Peter Glynne (a servant of Pemberton Hodgson), and two indigenous guides, Bobby and Chinchimar (Johnny), was formed, and set out from nearby Jimbour Station on 8 August 1845.

The land beyond Jimbour was largely unexplored by white settlers and explorers in Australia, and known only to indigenous communities and Pemberton Hodgson, who had travelled with Leichhardt for part of his journey through the region. The search party travelled westward from Jimbour station for two days until they reached the Condamine River, from where they commenced a passage north-west for 24 days, searching for campsites, bullock tracks, and any other evidence of Leichhardt’s party visiting the region. Within the first week of their travels they had reached a campsite abandoned by Leichhardt’s expedition, which Taylor loosely sketched on August 16 while the party was resting, maintaining their equipment, and surveying their position.

The following day the party continued their journey, following Dogwood Creek for 4 miles before changing course to the north-west, only to be met with impenetrably dense brigalow scrub. After attempts to clear the scrub over two days, the party agreed that Leichhardt could not have passed through such inhospitable bushland and altered their path to a northerly direction, passing through scrubby country before locating another camp of Leichhardt’s on 21 August. A few days later the party reached a large water hole where they came into contact with a large community of indigenous people. Describing the landscape and contact, Taylor wrote in his expedition diary on 25 August:

At about 11a.m. came on a large lagoon, very broad and perhaps 2 miles long. It is a magnificent sheet of water and covered with wild foul of all descriptions. The native name of this lagoon is Euröonbah – it is the largest and only body of water we have seen since leaving the Condamine. We followed its long reaches and opposite steep banks which were covered with a dense scrub amongst which the graceful Myall was seen bending gracefully over the water similar to the willow.

In consequence of meeting with back waters running with the lagoon we were obliged to leave it and proceed quietly on our way to round them, when we came suddenly on a large party of blacks fishing, but so intent on their occupation that we rode close up to the waters edge before they perceived us and were for some time quiet spectators of their amusement. An old ‘Gin’ who was sat down at a fire on the opposite side at length saw us and quickly uttering a loud yell dived instantaneously into an adjoining scrub followed by gins and piccaninies [sic] made a desperate rush up the bank abandoning huts, fish and even their beloved dogs.

Two black fellows, who had bathed seized their spears, brought up the rear, and these with some difficulty we persuaded to stop and hold a parley with us. Johnny tho’ not quite conversant with their language was nevertheless able to ascertain from them that they had seen Leichardt’s [sic] party some moons ago. They furthermore stated that the waters we were upon went away N.E. into a large body of salt water coming from the sea. Some of us went over and had a conference; in the meantime an old mammy who had taken up her position behind a tree and was narrowly watching our movements, seeing that we were friendly returned and commenced carrying off all the valuables from the camp. In one of her nets was a large eel which the old woman gave us, in exchange we gave the blackfellows some tobacco which they returned after tasting and smiling not knowing what it was, some strips of handkerchiefs appeared more acceptable. [16]

The party continued their search for another 9 days. Along the journey Taylor took another sketch of the party when camped, domiciling themselves under hastily fashioned gunyahs to protect them from sporadic rainfall. The rains made fresh water more plentiful in the otherwise dry central Queensland landscape, but made it more difficult to discern the tracks left by Leichhardt’s expedition party. As the party marched on, patience wore thin and tensions flared. In the early hours of 1 September, the group discovered Hodgson asleep when he was meant to be on piquet to protect the camp. Taylor wrote:

About 3 o’clock the next morning whilst most of us were sound asleep we were suddenly around by the report of gun and immediately sprang to our arms prepared to encounter whatever danger might be in store for us; of its description we were not long ignorant for a loud voice was calling to know whose watch it was and no answer was returned. The watch himself no less a person than Hodgson, in being busily engaged in not looking for us but in looking out for himself, being snugly envelopped [sic] in his blankets and coiled away in a warm corner of his gunya where he was found asleep. Had this been the first time such an occurrence taking place a gentle call to him would have been all necessary, but being the third time it was thought advisable by those awake to fire a gun and rouse all hands so that the event might be publicly known to us all which would most probably have the effect of shaming him into doing his duty. [17]

On 3 September, the party again fell into disagreement, this time with explosive outbursts. Taylor recounted the incident:

We then bore away from the creek striking across ridges until we arrived at some very high ranges spurs which formed a series of valleys thro’ which the gullies tributaries of the sandy creek take their course. These ranges we could perceive as we advanced were spurs running away from a very high range on our right and the direction of which was from SE to NW being probably a spur of the Main Range. It was therefore evident to us that the course that Hodgson was steering but of which he had not informed any of us would if continued had us over very broken country, gully after gully and tier over tier of mountains should we either ascend the range and head the gullies, or descend and get to the creek which we could follow up easily and which moreover would not lead us much out of the course in which we considered we should sooner or more readily fall in with Dr Leichardt’s tracks and by pursuing the latter plan we should have a chance of finding his camp should he have struck on the creek higher or follow it any distance. We therefore on arriving at the summit of a very high range and very rocky as many we had previously crossed, halted and called to Hodgson who was on ahead to come back and hold a consultation, as it is usual in the Bush under such circumstances.

On coming back to us we mentioned in a quiet way the substance of our opinion as before named hinting that it would be advisable to change our course until we had cleared the broken country ahead of us. To this Hodgson who evidently was in no good humour as it is often the case with him replied “that it was my course and to that I mean to stick”. Some very high words passed Hodgson taunting us with being afraid of mountains. We replied we were ourselves no new hands in the Bush and were determined not to follow him in any wild goose chase, but we were anxious to find Dr Leichardt’s tracks. As we found it out of the question to reason with him we considered the best plan was part. On Hodgson advancing in a furious rage to take the saddle off Rodger’s horse Rodgers said having ridden the horse out on the expedition he had a right to take him in again. On this Hodgson drew his sword and swore he would have Rodgers horse of his blood. We divided the rations, Rodgers, Taylor & Isaac & Johnny taking enough for nearly three weeks to enable us to reach the downs. Hodgson left us with the rest of the party proceeding the very way we wished him to go. We had in our party six horses including two for pack belonging to ourselves bidding forward except Hodgson; returned to our last night’s camp wishing to have the evening to arrange our plans preparatory to making an early start on the morrow. [18]

Taylor’s description of events largely corroborates with Pemberton Hodgson’s own account of the incident, though Hodgson’s account omits the severity of the tension in the camp. Musing on his time in Australia, Hodgson wrote:

After proceeding six miles in a N. 60° W. course, and crossing over three spurs of sandstone ranges, very steep and rocky, running to the south-west, and being in advance with my blackfellow Bobby, nearly a quarter of a mile, I found the rest of the party had halted.

Not knowing the reason, I cooïed, and received an answer. I then imagined something had happened to the packs, and waited patiently. I was soon undeceived; on walking back to those behind, I found them quietly smoking their pipes, and looking so fierce, that it appeared almost dangerous to approach them. One of the party, on my inquiring the reason of the delay, said, he was determined to proceed no further in that line, it being too steep and mountainous, and not a right course. I told him and all, that N. 60° W. was my line, and I intended to pursue it till I met with some more grievous impediment, and that any might return who did not wish to proceed with me.

The attack came very unreasonably from a man, who was then using two horses I had lent him, and to whom their sacrifice, therefore; could not be any loss. Had it come directly for the two who alone had their own horses, I might have listened more patiently; as it was I found there was an equal division; so I determined on giving the four who wished to return three weeks supply of everything; a suitable supply rations &c., was accordingly weighed out and delivered over.

The young man to whom I lent the horses wanted to stick to his; but that not suiting my ideas of “suum cuique,” I insisted on a resignation, which was at last acceded to – not that I wished to see them pushed for the means of conveyance; but I knew there was a sufficient number independent of my own. The scene ended, therefore, unpleasantly to all; but I congratulated myself that it was only two days before it had been generally agreed that all of us should make a retrograde movement, as our four weeks term was expired, and there was no probability of doing more than we had done without going the whole way which were not in a situation to do. I had some time before mentioned to the rest of my plans, namely, to proceed N. 60° W. in as direct a line as possible till we ought to cross the Doctor’s line, supposing he had gone his N.W. course, from the spot on which we last saw signed. This we were within ten miles of, and, therefore, I would not willingly give up my plan; but it is over, and I have no doubt some of them regret their conduct, as much as I did the necessity of shewing determination. [19]

The party split, with Taylor, James Rogers, Frederick Isaac, and indigenous guide Johnny returning to Jimbour station, and Hodgson, William Calvert, Peter Glynne and indigenous guide Bobby proceeding forward. On the return journey, Taylor continued to sketch scenery, producing a drawing titled Mt Domville on the Leichhardt River on 6 September. On 10 September, the two parties met again. Taylor wrote;

During this time Rogers and Taylor were engaged at the camp making the tea and Isaac and Johnny were having a “piola” with the blacks, the attention of all of us whites and blacks was drawn towards a man who came riding up at full gallop sword in hand to our camp and our doubts as to who it was were soon dispelled by seeing Hodgson, his look as wild as ever and from his appearance we were at first inclined to imagine that he must have been hunted by the blacks.

On coming to our camp he suddenly halted, and no notice being taken of him he asked Roger’s and Taylor “if they had nothing to say” an don being told “no” he wheeled around and made up to Isaac to whom he observed that “that day we parted and now we meet again”; a short “yes” being the answer he clapped spurs to his horse and rode back to his camp. Calvert soon afterwards came to see us and was of course heartily welcomed. [20]

The parties continued their return separately, with Taylor’s party discovering an indigenous mortuary platform, described by Taylor as a “pooram”, near Dogwood Creek. Writing in his dairy, Taylor noted:

On going to it we found it was four forked sticks about 12 ft. long dove into the ground with cross pieces laid on them and on these again a number of sapplings [sic] laid broadways which had been erected by the blacks as a sort of a repository for their dead. When a black dies his body is carried for a long distance and one of these things erected on which it is laid partly decomposed and eaten by the crows and Hawks. The bones are then carefully taken down and wrapped up and carried about by the friends of the deceased with much care for some time. They probably imagine there is much charm in them and that they transmit to their possessors some of the good qualities inherent to the departed when he lived. Our black boy Johnny from superstitious reasons was afraid to venture near the spot. [21]

Taylor subsequently produced a loose sketch of the structure, this being a rare visual account of indigenous Australian burial practices, and almost certainly a unique representation of such architecture produced in colonial Queensland.

Taylor and his three companions returned joyfully to Jimbour station on 19 September 1845, firing all their guns as a salute when they saw the homestead on the horizon. Hodgson and his remaining party arrived two days later, bringing the 6-week journey to an end. Hodgson sent a report of the expedition to the Sydney Morning Herald, which was published in that newspaper on 11 October. [22] Taylor’s detailed diary was never published, but analysis of this document will reveal much about the flora and fauna along the expedition route, along with Taylor’s observations indigenous Australian culture that he encountered during the expedition.

16. Thomas John Domville Taylor, Journal of the expedition in search of Leichhardt, 1845 [Manuscript]. National Library of Australia PIC MSR 14/1/6 Volume 1190 #PIC/20229/1-2.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Christopher Pemberton Hodgson, Reminiscences of Australia: with hints on the squatter’s life. London: W.N. Wright, 1846, pp. 343-345.

20. Thomas John Domville Taylor, Journal of the expedition in search of Leichhardt, 1845 [Manuscript]. National Library of Australia PIC MSR 14/1/6 Volume 1190 #PIC/20229/1-2

21. Ibid.

22. Christopher Pemberton Hodgson, ‘Leichardt’s Party’, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 October 1845, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12882764.

Taylor’s father, Mascie Domvile Taylor died on 9 October 1845. [23] It is perhaps for this reason that Taylor departed Australia for London on 16 June 1846 aboard the General Hewitt, stopping in Pernambuco during the voyage. [24] Tummaville was acquired in 1846 by Thomas Gore, brother of St George Richard Gore who owned neighbouring station Yandilla. [25] Taylor never returned to Australia, though keen to preserve his memory of his time in Queensland, in 1847 he commissioned Chester-based artist George Pickering to complete an ink wash sketch of the interior of his hut at Tummaville. Taylor died on 14 September 1889, at Trouville Road, Clapham Common, and was survived by his wife Charlotte. [26]

Taylor’s drawings, journal and sketchbooks are among the first graphic and written accounts of life on the Darling Downs. Their importance lies not only in their dates of execution, but the fact that together present a rare first-hand account of the lifestyles of the earliest settlers in the region, as well as consider the increasingly tense yet complex relationship between indigenous and settler communities in this part of Australia. Further analysis of these materials, particularly Taylor’s journal, will reward researchers with insights into early observations of indigenous cultures in central Queensland, as well as reveal how the earliest European communities negotiated the terrain to create livelihoods in the region.

23. William Phillimore Watts Phillimore, ed., Shropshire Parish Registers: Diocese of Lichfield, vol 1. Shropshire: Shropshire Parish Register Society, 1900, p. iv (between pp. 250-251).

24. ‘Clearances’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 1846, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12887879.

25. Magnificent Run on the Darling Downs, Together with 1225 Head Choicest Cattle’, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February 1846, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12885370.

26. Flintshire Observer, Mining Journal and General Advertiser for the Counties of Flint and Denbigh, 21 September 1889, p. 6.

Archival Sources

New South Wales Government Gazette, 27 October 1843 (no. 90), p. 1395.

SLQ, Colonial Secretary’s letters received relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland 1822-1860, A2 series, reel 11, CF Ref. No. 41/00114, Letter from Domville Taylor to the Colonial Secretary, 4 January 1841, requesting access to Moreton Bay settlement. https://content.slq.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/0005-198221-slq-a2-series-reel-a2.11-2014-09.pdf.

Primary Sources

Thomas John Domville Taylor, Journal of the expedition in search of Leichhardt, 1845 [Manuscript]. National Library of Australia PIC MSR 14/1/6 Volume 1190 #PIC/20229/1-2.

Secondary Sources

Christopher Pemberton Hodgson, Reminiscences of Australia: with hints on the squatter’s life. London: W.N. Wright, 1846, pp. 343-345.

Henry Stuart Russell, The Genesis of Queensland: an account of the first exploring journeys to and over the Darling Downs: the earliest days of their occupation; social life; station seeking; the course of discovery, northwards and westward; and a resume of the causes which led to the reparation from New South Wales, Sydney: Turner & Henderson, 1888, p. 328.

Joseph Foster, ed., Alumni Oronienses: the members of the University of Oxford 1715-1886: their parentage, birthplace and year of birth, with a record of their degrees, vol. 4, Oxford: Parker & Co., (c.1891), p. 1395.

Thomas Hall, The Early History of Warwick District and Pioneers of the Darling Downs, Toowoomba: Robertson & Provan, Ltd, 1925, p. 21.

William Phillimore Watts Phillimore, ed., Shropshire Parish Registers: Diocese of Lichfield, vol 1. Shropshire: Shropshire Parish Register Society, 1900, p. iv (between pp. 250-251).

Newspapers

Flintshire Observer, Mining Journal and General Advertiser for the Counties of Flint and Denbigh, 21 September 1889, p. 6. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/flintshire-observer.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Departure’, 15 September 1842, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12423403.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Moreton Bay’, 12 September 1843, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12413308.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘News from the Interior’, 9 August 1844, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12413468.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Leichardt’s Party, 11 October 1845, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12882764.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Magnificent Run on the Darling Downs Together with 1225 Head Choicest Cattle’, 18 February 1846, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12885370.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Clearances’, 17 June 1846, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12887879.

The Australian, ‘Shipping Intelligence’, 21 December 1839, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36860100.

The Omnibus and Sydney Spectator, ‘Peel’s River’, 27 November 1841, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228064526.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, ‘Original Correspondence’, 27 August 1842, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2557221.

Online Sources

Ray Kerkhove, Mapping Frontier Conflict in south-east Queensland, 2017, Harry Gentle Resource Centre.