Abstract

Women from early colonial families played an important role in the call for women’s rights. This project explores the links between early settler families and the later successes of the nineteenth century women’s movement. As the century progressed, women’s movements developed through the western world.

Some key early Queensland families are identified, and women’s stories elicited, as part of a larger project undertaken on the political history of women (and their organisations) leading to white women attaining the vote in Australia in 1903, and in Queensland in 1905. To deepen our understanding of these women and the issues they faced, it is necessary to grapple with the broader concepts of settler colonization, race, class, and gender.

Acknowledgements

As a Visiting Fellow of the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, I wish to acknowledge the generous assistance and support of the Gentle family. Through the Harry Gentle Resource Centre they assist the ongoing study of early Australian history and promote the study of Social, Economic, Political, Women’s, Indigenous and Environmental history and innovative methods of research. Queensland history is more fully understood when the Moreton Bay settlement is included. I am indebted to the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, and for the ongoing support from Dr Lee Butterworth, Dr Dorothy Wickham, Dr Ray Kerkhove, Dr Janis Hanley, Jan Richardson, and Distinguished Professor Mark Finnane.

Description

Some fascinating questions emerged while researching the links between the early settler women in Queensland, and later colonial feminisms such as the right to vote. What was the role of ‘pioneering’ women? What was their perception of the changes in women’s rights? What was function of women during early settlement? Married women, for example, were legally unable to own property or have custody of their children until 1890. What were women’s thoughts about the context of Empire, and the invasion and appropriation of Indigenous lands? Given settler women’s early exposure to Indigenous women, what did they learn about Indigenous women’s involvement in governance?

This project examines some key early women settlers, who later emerged as leading figures in the women’s movement. It looks at how the suffragists achieved the vote in Queensland. Was the intergenerational transmission of values through families and family dynasties important to the colonial women and their allies who led the campaign for women’s political rights?

Dr Deborah Jordan, Research Fellow, in History at Monash (adjunct); Petherick Reader, National Library of Australia; and award-winning professional historian and biographer; specialises in research on women at the intersection of history, literature, and environment, addressing issues of gender, race and class.

Teaching History at Flinders University, South Australia for nearly a decade in the 1980s, Deborah undertook post-doctoral research on the household economy examining induction of First Nations women into mission economies.

Researching cultural and literary history at the University of Queensland from 2002, she published a selection of the love letters of Nettie and Vance Palmer 1909-1914, Loving Words, and she was the lead researcher on climate change narratives for the Australian Literature Online database at the University of Queensland. Australian Women’s Justice: Settler Colonisation and the Queensland Vote (2024) is her eighth book.

Locating Early Colonial Feminists

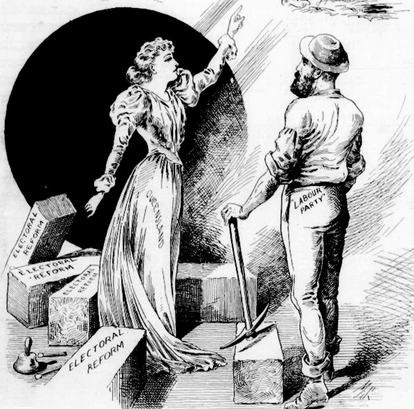

Qld. Parliament, History Women’s Suffrage

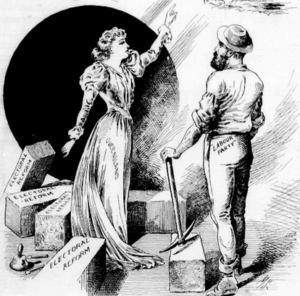

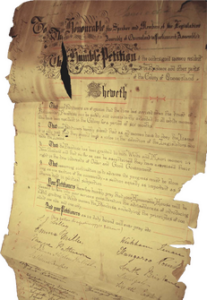

Three suffrage petitions were presented to the Queensland Parliament. Women signed the petitions using their own Christian name and with a close reading, the extent of how widespread the movement was, becomes clearer. The names of the ‘early families’ are evident among women holding leadership roles.

To address the lack of primary sources on progressive women, with the Parliament, former parliamentary librarian John McCulloch, the Queensland Family History Society, and myself collaborated to have the three suffrage petitions digitised. Biographical material on the first signatories was undertaken. This has facilitated a wonderful insight into the participation of ‘ordinary’ women, working women with at least one former elderly convict being identified.

The intricate details of genealogy can limit our understanding of our forebears when seen in isolation from the great shifts in the position of women. Which women were prepared to sign the petition, and which petition (whether expedient or democratic) provides a political filter.

Queensland Parliament, History Women’s Suffrage.

The Families

Aura Holdings, Honouring Angela Francis: A woman who made a difference

Angela and Arthur Morley Francis immigrated in the early 1860s and their daughter Charlotte was born in 1866, both key figures in suffrage meetings and community building. Both Elizabeth Brentnall’s daughters were involved in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, of which she was the Queensland president and a key advocate of suffrage. Other early settler suffragist families were identified notably Sarah and Charles Lilley; Fanny Trundle and her family notably her son Charles who married Charlotte Ball; and many others all worthy of further research. A belief in the need to recognise women’s citizenship was taken up very widely across all sections of the community, a surprising finding given the lack of historical record.

Women Involved in Deputations

Reported in the mainstream media, the women involved in numerous deputations to the various premiers in Brisbane and across the colony could be identified.

JOL, SLQ, Neg. No. 64485.

In this significant contingent in 1894, for example, key senior women philanthropists, early headmistresses and wives of headmasters, pastoralists’ wives, leading business leaders’ wives, and political dignitaries on levels of government can be seen. All the women can be identified through their genealogies and it was found that some of the very early free settlers who experienced the long sea passage, and acute cultural disruption, had gone on to play leading roles.

Lady O’Connell (1813-1903) arr 1854

Eliza Clark née Mullarkey, born in Sydney in 1843

Elizabeth Edwards (1840-1914), arr 1869

JOL, SLQ David and Mary McConnel Neg. No. 65979

Angela Francis , arr 1862, died 1910, and daughter Charlotte Godwin King, b1866

Mary McConnel (1824 –1910), arr 1848

Janet O’Connor (1827–1895), arr via Victoria 1855, 1875

Executives of the Suffrage Organisations

A key way to locate early colonial feminists is through the organisational histories of the suffrage associations. When we look at these key suffrage organisations that emerged in the 1880s, we can delve into the biographies of the executive, named in newspaper reports (even if the membership is not) and so we can exact a clear idea of the women involved.

Some senior women did not sign the suffrage petitions, notably Elizabeth Brentnall, and nor did she participate in deputations, yet as a charismatic long-term leader of the WCTU she played an instrumental role. We know that she was the colonial president of the WCTU and played a significant part.

Emma Reading nee Paten (1844-1917) emigrated with her family as a girl in 1858, married but was left a widow in 1876 with five young children. She was known as a philanthropist and religious leader. The secretary Agnes Cramb, later Keith (1836-1914) arrived as a newly-wed, soon after Separation and was a writer, journalist and newspaper proprietor. Christina Corrie came from New Zealand, where Maori and Pakeha (white) women had voted since 1893.

The democratic suffragists achieved ‘one woman one vote’.

Executives of the suffrage organisations:

Women’s Franchise League 1889-1891 – President Emma Reading.

Women’s Equal Franchise Association 1894-1905 – President Emma Miller.

Women’s Suffrage League 1894-1903? – President Leontine Cooper (and Pioneer Club).

Women’s Christian Temperance Union – Colonial president Elizabeth Brentnall.

Suffrage Superintendent – Charlotte Trundle.

Queensland’s Women’s Electoral League 1903 – President Christina Corrie.

Women Workers Political Organisation 1903 – President Emma Miller.

![Portrait of Mrs. Emma Miller: [suffragette movement in Queensland]](https://harrygentle.griffith.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Emma-Miller-195x300.jpg)

Comments and Conclusions

To make the links between the early group of settler women and later developments a number of significant questions not often addressed, such as the role of ‘pioneering’ women, their widespread involvement in non-traditional forms of labour, their early work in community building establishing and running hospitals, charities and schools, their perceptions of the changes in women’s rights between penal outpost and free settlement, needed to be aired.

The generation of women who emerge as most important in achieving the women’s vote were all born in the 1830s the same decade as the 1932 Reform Acts in Britain and chartist agitation, arrived in Queensland in the late 1860s and early 1870s, and had decades of political experience by the final years of the campaigns. Some of the white women were clearly too elderly to participate in the movement in the 1890s when the focus was on the vote, but the connections between mothers and daughters or daughters-in-law are numerous. Take the early McConnel’s who took up land in 1841. Mary McConnel was elected to the first Council of the Women’s Equal Suffrage Association in Brisbane in 1894.

JOL, SLQ Mary Emma McConnel (1860 – 1929) Neg. No. 56320 https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183513872102061

A leading light in the movement, May Jordan McConnel (her daughter-in-law and the daughter of the early parliamentarian Henry Jordan who arrived in Queensland in 1856) was elected its first treasurer.

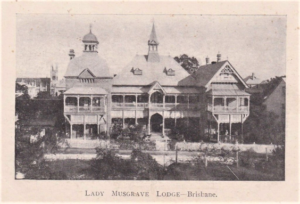

Women, such as Elizabeth Brentnall and Emma Reading were involved in both philanthropy and advocating for women’s suffrage. They were experienced in running charitable institutions notably the Lady Musgrave Lodge for homeless women.

Given an understanding on the suffragists’ origins, family context, religion and public involvement, time of arrival, different ways of framing them evolved: imperial feminisms, maternal feminisms, colonial feminisms, and commonwealth feminisms. The bases of the later differences between those women who advocated strategies of expediency (plural, property vote) and those who called for justice and democratic suffrage (one woman one vote) became clear and is significant to the research in this project.

Children’s Hospital Foundation, Our history, https://childrens.org.au/our-history/.

Outcomes

This new research became vital in reshaping my wider study of the suffragist movement and became an essential first chapter in my latest book, Australian Women’s Justice: Settler Colonisation and the Queensland Vote (Routledge, 2024), which addresses European occupation, including race, class, women’s property rights, the property vote and violence, not only between men and women but between colonial, European and Indigenous peoples.

In addition, recommendations of key Queensland suffragists and colonial writers have been submitted to the Australian Dictionary of Biography for the forthcoming volume on overlooked colonial women; a talk at the Queensland State Archives; short biographies of Queensland suffragists contributed to the Harry Gentle Resource Centre’s dictionary of early Queenslanders; and short biographies of key New Woman journalists contributed to the AUSTLIT database.

For more information and research:

Deborah Jordan, Australian Women’s Justice Settler Colonisation and the Queensland Vote, London & New York, Routledge (2024)

The introduction and part of the first chapter ‘Settling, Philanthropy and the Vote’ is available for preview here.

QSA Talk: ‘What We Want’: Queensland’s Colonial Feminisms

Deborah presented this talk at the Queensland State Archives on Thursday 2 November 2024. You can watch the recording here.