About the project

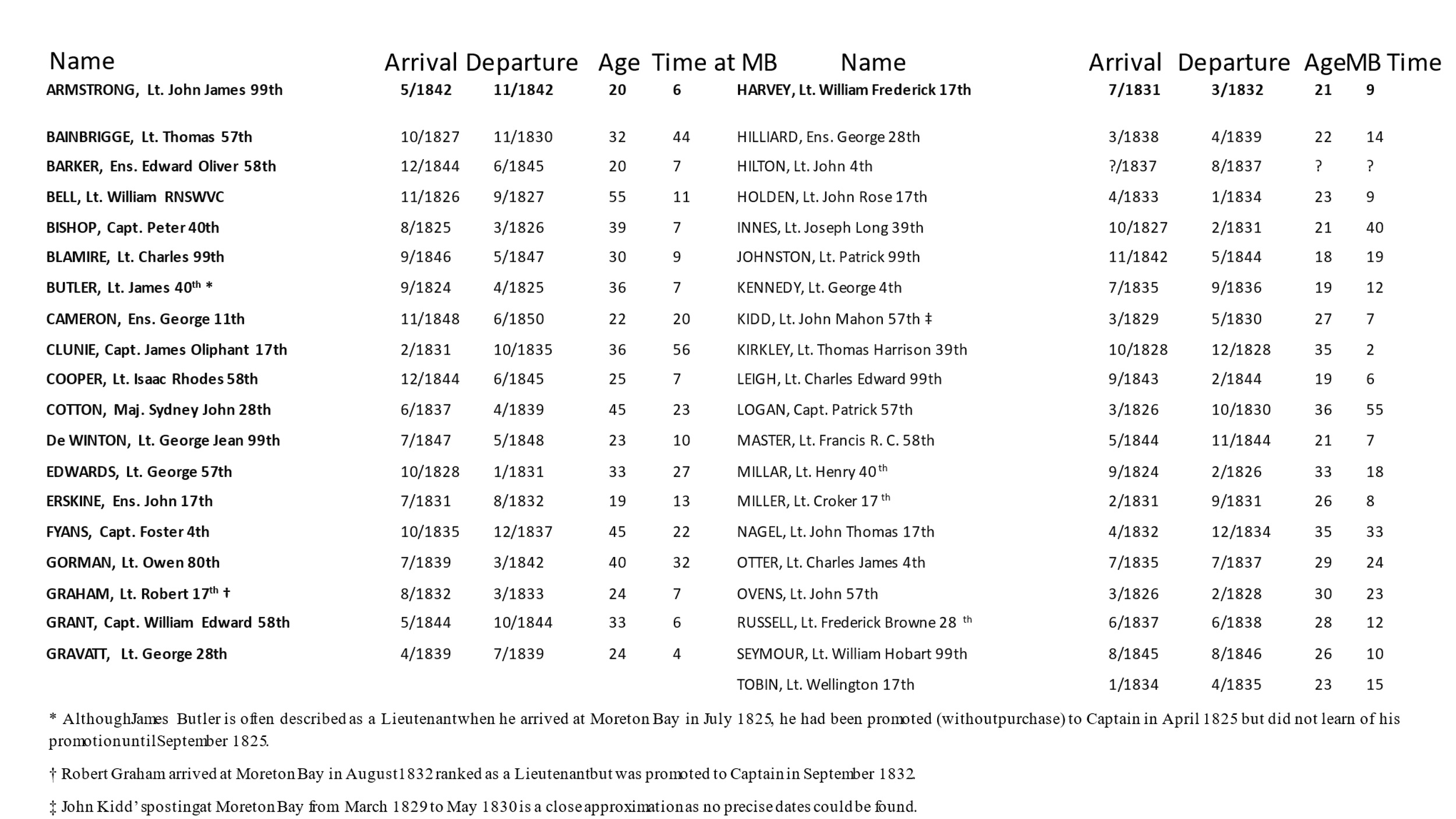

Whenever we think of the British military officers at the penal station of Moreton Bay, we invariably think of the commandants like Millar, Logan, Clunie, Cotton, Fyans and Gorman. Yet for every commandant who served at Moreton Bay, there was on average another two or three staff officers who were equally hard-working yet, for the most part, remain entirely unknown. Would we have heard of Lieutenant Charles Otter if not for the rescue of shipwrecked Eliza Fraser? Would Lieutenant George Edwards of the 57th Regiment be known but for being the first to report of Patrick Logan’s spectacular murder in October 1830?

This project explores those subalterns whose roles at Moreton Bay have been mostly eclipsed by their better known commanding officers.

About the author

Rod’s life-long fascination with Queensland history has led him to author and co-author almost fifty journal articles, books and book chapters, dealing with the roles of the military in Queensland. The topic of these publications range from the British red-coats posted to early Moreton Bay from 1824, the rise of Volunteer Forces in the 1860s, the Colony’s early school cadet movement, through to the service of Queensland Aborigines in the First A.I.F. As a Visiting Fellow with the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, Rod’s research on the British Army at Moreton Bay, 1824 to 1850 has contributed greatly to the development of the centre’s biographical and historical database. Sadly, Rod passed away in July 2022.

Legacy of a convict colony

When the British Government ended transporting convicts to the American colonies following the American Revolution in the late 18th century, Australia was chosen as an alternative site for founding a penal colony. The first fleet of eleven convict ships arrived in Botany Bay on 20 January 1788 and the town of Sydney, New South Wales was founded.

In 1823, British explorer John Oxley sailed north from Sydney in search of a location to establish a place of secondary punishment for hardened criminals and recidivist prisoners. While at Moreton Bay, Oxley discovered and explored the lower part of the Brisbane River, subsequently recommending it as a site for a convict settlement. He returned in September 1824 with a detachment of British soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Henry Millar of the 40th Regiment, who first commanded the new penal settlement of Redcliffe. This settlement was soon found unsuitable and in 1824 moved up-river to Brisbane Town.

In 1839 transportation to the Moreton Bay Penal settlement ceased and it closed in 1842 when Moreton Bay was opened up for free settlement. With the end of convict transportation the role of the British soldier changed to serving in the Mounted Police, maintaining civil order, protecting settlers from frontier conflicts with Aboriginal peoples and defending communication and trade routes as the pastoral frontier expanded.

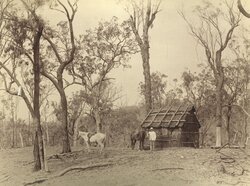

Today, little remains of the legacy from Moreton Bay’s convict era apart from structures such as the Commissariat Store, the old Windmill, some archaeological remains at Redcliffe and Dunwich, as well as numerous place-names. Looking at Queensland’s SE corner there are examples of Hilliard’s Creek (George Hilliard 28th Regiment), Mount Gravatt (George Gravatt 28th Regiment), Logan Creek and Logan River after Patrick Logan, Mount Cotton (Major Sydney Cotton 28th Regiment), Clunie’s Flats (James Clunie 17th Regiment), Gorman’s Gap (Owen Gorman 80th Regiment), Lockyer Creek (Major Edmund Lockyer 57th Regiment), Norman Creek (Sgt John Norman 40th Regiment), Ovens Head (Lieutenant John Ovens 57th Regiment ( not to be confused with his more famous uncle Major John Ovens also of the 57th Regiment), and even Coochiemudlo Island was once named Innes Island after Lt Joseph Long Innes 39th Regiment.

Moreton Bay was just one among many postings in the Australasian Colonies but, with the closure of small outposts in the continent’s north, in what later became the Northern Territory, Moreton Bay became the most remote garrison in Britain’s global empire. From 1824 to 1869 approximately 1,500 British soldiers served at Moreton Bay.

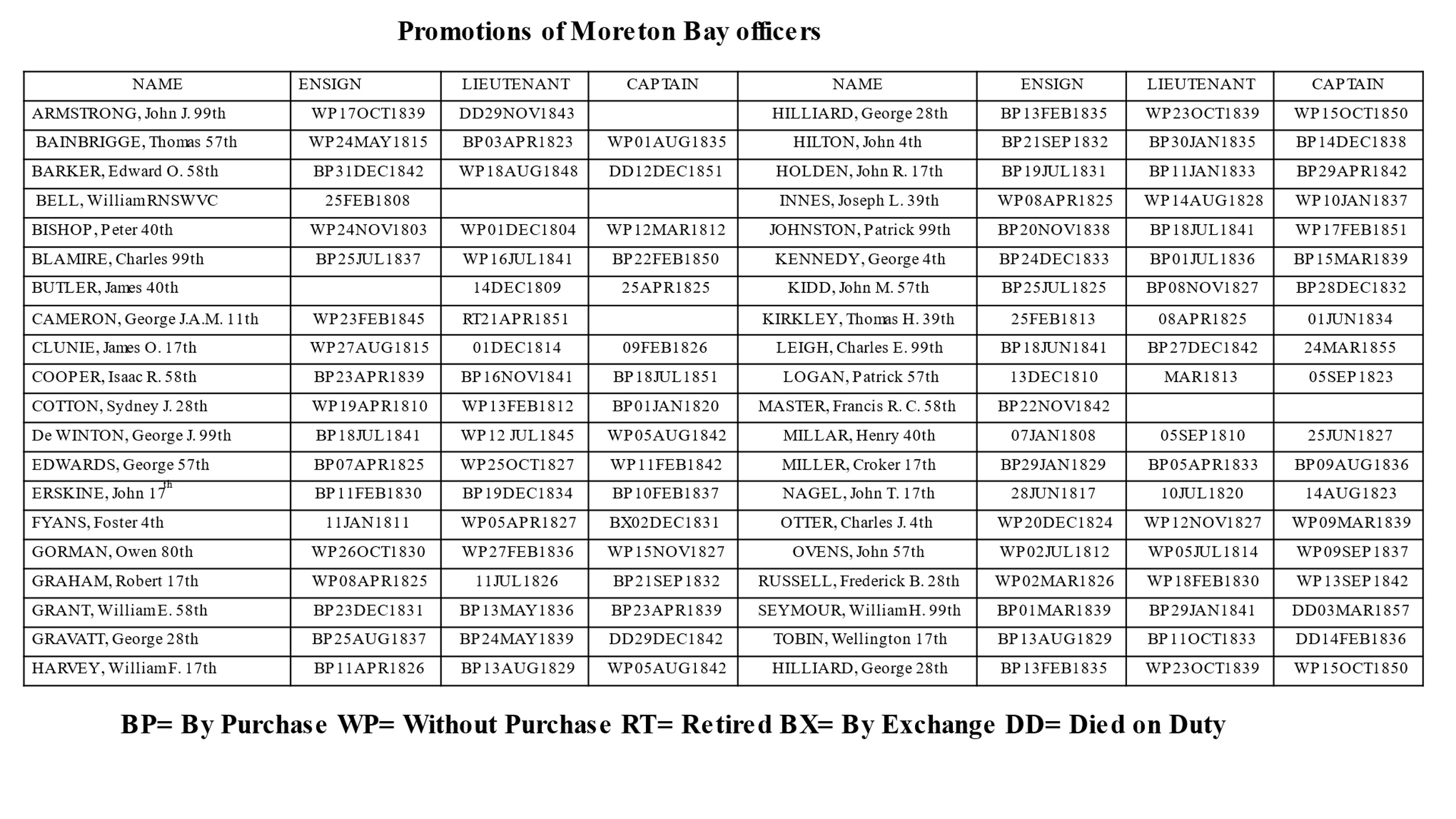

Subaltern military officers

Think of the military officers posted to Brisbane Town during its convict period of 1824 to 1841, and names such as Henry Millar, Patrick Logan, James Clunie, Foster Fyans, Sydney Cotton and Owen Gorman immediately spring to mind. Yet these commandants could not have fulfilled all their duties without the support of their staff of subaltern officers. When both Logan and Clunie commanded the settlement from 1826 to 1835, it was usual for the most recently arrived subaltern at Brisbane Town to hold the post of either Superintendent of Works or Assistant Engineer, although none of these officers would have possessed the skills or knowledge for the role, and hence relied upon overseers for guidance. This practice appears to have begun with Lieutenant John Ovens 57th Regiment, before the role transferred to Lieutenant Joseph Innes 39th Regiment, and thence to Lieutenant Thomas Bainbrigge, Lieutenant George Edwards, Lieutenant William Hervey and finally Lieutenant John Nagel, even though Captain Clunie was strongly opposed to the appointment of the latter.

For the most part, the subalterns’ duties were mundane and this in turn led to boredom. Assistant Surgeon Dr Fitzgerald Murray described the military officers he encountered at Brisbane Town as ‘desperate grog drinkers and cigar smokers’, although he was prepared to consider Lieutenant George Edwards an exception to this rule. On rare occasions these subalterns attracted attention, such as when Lieutenant Charles Otter of the 4th Regiment went north to rescue Eliza Frazer, or Lt Frederick Browne Russell of the 28th Regiment who searched for two sailors from the Duke of York shipwreck in 1837, only to learn they had both been murdered by the Huon Monday (Eumundi) Aborigines. Even Lt George Hilliard of the 28th Regiment received considerable public acclaim and presentations when he led a Mounted Police detachment directly after his Moreton Bay posting and was responsible for the capture of notorious bushrangers.

Part of this neglect of the Moreton Bay subalterns was due to the fact that many were posted to Moreton Bay only briefly, such as Lieutenant Thomas Kirkley of the 39th Regiment who was present less than two months. These brief postings stand in contrast to the commandants whose tenures were much longer and saw several subalterns pass under their command. Captain Logan might have had the longest stay but it was cut short by his murder after 4 years 7 months and was eclipsed by Captain Clunie, whose posting was the longest at 4 years 8 months. Of course, the number of subalterns under a commandant’s command was determined by the number of soldiers forming the detachment, and the size of this detachment was in turn determined by the number of convicts kept under guard. The usual ratio of convicts to soldiers across Australian penal stations was roughly maintained at 10 convicts to each soldier. Likewise, an ensign (when assisted by an able NCO) took charge of approximately a dozen soldiers, while a lieutenant commanded around thirty soldiers, and a captain was usually appointed over a force no greater than a hundred redcoats.

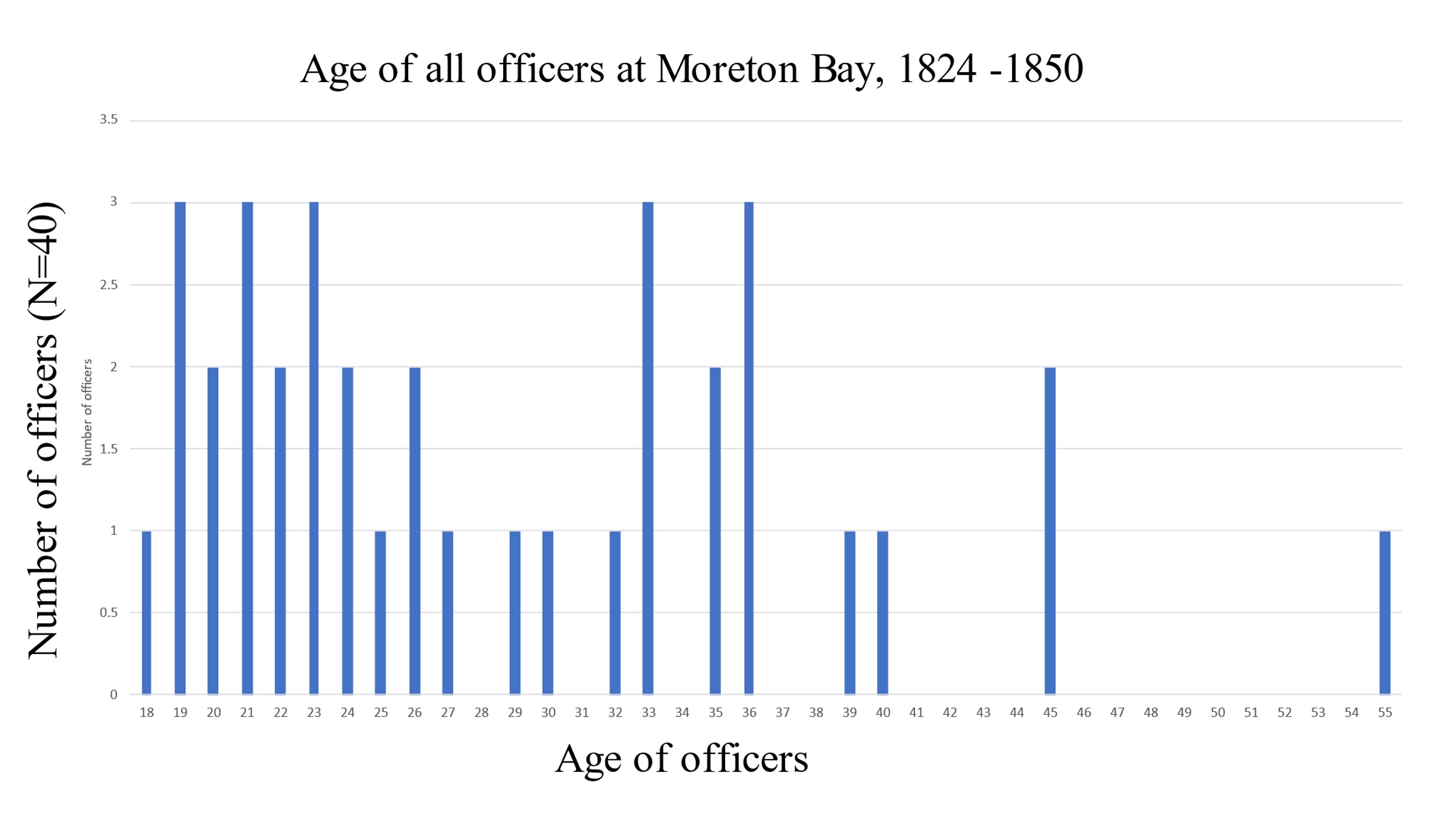

This paper refers to these officers as subalterns rather than junior officers, because of the 40 officers who served at Moreton Bay during 1824 to 1850, only seven were below the age of twenty-one, while the average age of a subaltern was 36.5 years. When taken together, these ‘junior officers’ were seldom junior in age and there were other discrepancies as well, such as the oldest subaltern (Lt William Bell RNSWVC aged 55) and the youngest (Lt Patrick Johnston 99th aged 18) both held the same rank even though separated by an age gap of 37 years. All this tends to demonstrate how slow promotion could be in a peace-time army when one lacked the financial means to purchase one’s advancement. This leads to the subject of the purchase system of attaining rank.

The purchase system of promotion

Today, it is common for military officers to undergo years of education and gruelling training to obtain their first commission, but back in the period between Waterloo and the Crimean War, variously called the ‘Long Sleep’ or the ‘Great Peace’ by British military historians, the criteria for a promotion in the army was largely by means of the purchase system.

It should be noted that the purchase system was peculiar to the army alone as the other branches relied upon more rigorous methods. The ‘scientific corps’, that is the artillery and engineers, required intelligent and educated men due to the nature of their service, and both needed extensive study and examination. Similarly, the navy had a long-established tradition of lengthy apprenticeships beginning when one was quite young and involved the study of quite demanding navigational mathematics. The most common way of becoming an army ensign at this time was simply to purchase your commission. No training, no experience or education was necessary, all that mattered was whether you had the funding, had attended the ‘right’ public schools and your parents had the right social connections. It is therefore no surprise that officers tended to come from the aristocracy, the landed gentry or aspiring middle-classes as the cost of an ensigncy, as well as the expenses of uniforms, weapons, accoutrements, mess bills, regimental charities and countless other incidentals, excluded any but the wealthier strata of society. This did not mean that those from aristocratic families always purchased their promotions, any more than those of humble origins were excluded from holding a commission.

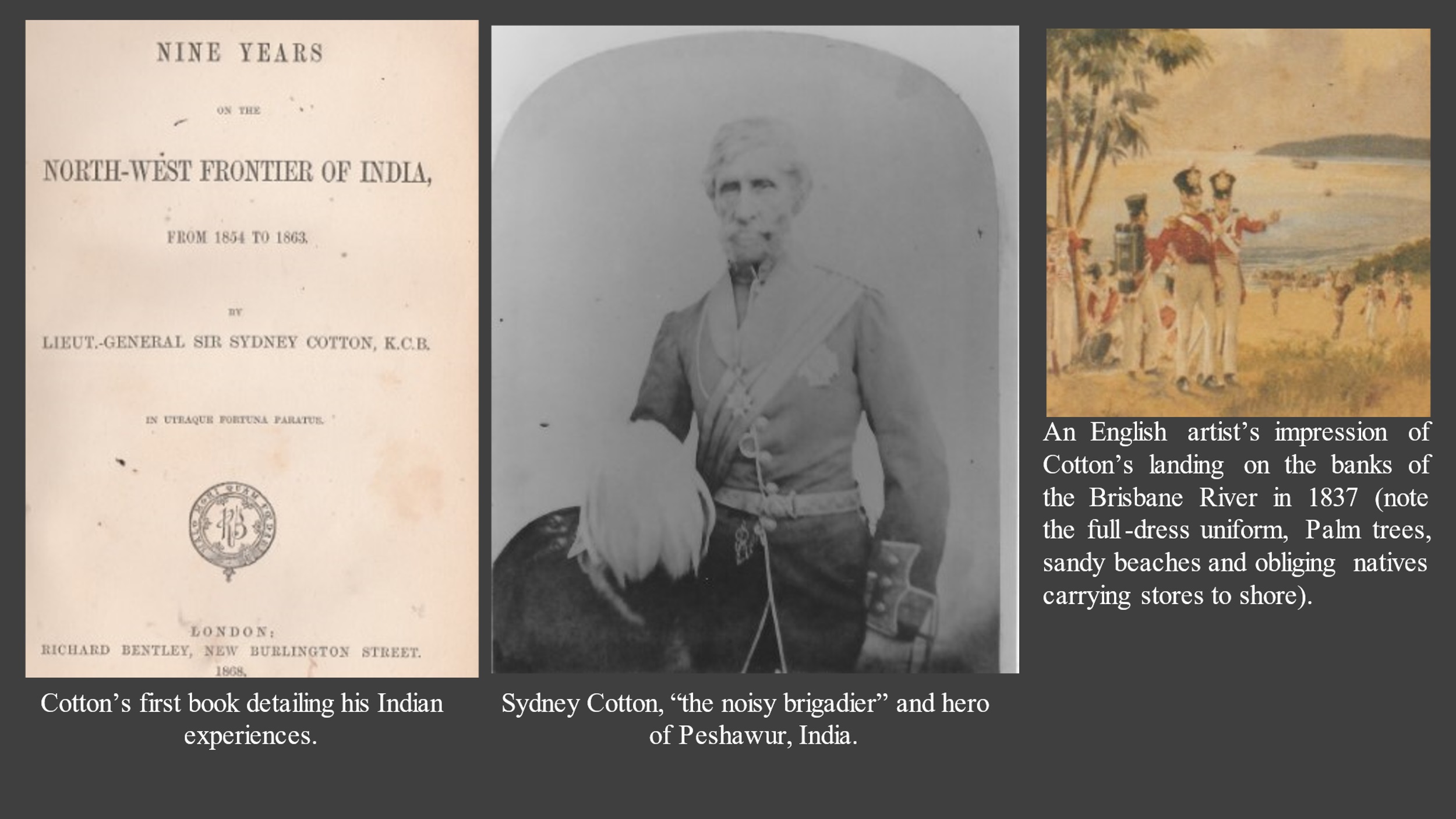

For example, Sydney Cotton and Peter Bishop both came from privileged backgrounds, with Cotton’s own lineage reading like a page from Burke’s Peerage. His cousin, Sir Stapleton Cotton (often described as ‘Wellington’s right arm’) was raised in the peerage to Baron Combermere in 1814, with Sydney Cotton appointed his Aide-de-Camp when serving in India from September 1825 to November 1827. Likewise, Peter Bishop was born at Bishopcourt, Ireland, into the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and married Julia Talbot, sister to the Earl of Shrewsbury. The point of comparison here with Cotton and Bishop is that both came from well-connected and wealthy families yet neither man ever used the purchase system to obtain promotion. By contrast, there were officers like Owen Gorman who began his career as a private in the 58th Regiment, and must have possessed the acumen to rise through the non-commissioned ranks to sergeant-major and then to quarter-master. The position of quarter-master could be held by either a senior non-commissioned officer or a subaltern, and it appears Gorman used this position to gain his ensigncy by seniority in 1830, without purchase at the advanced age (for an ensign) of 31.

While obtaining an ensigncy imposed an initial financial burden on the officer or his family, it was possible, if one was patient, to obtain further promotions simply by the process of seniority as with each promotion, every officer moved one step higher in the regimental ladder. The most senior lieutenant became a captain, while the second most senior lieutenant now became the most senior in line for promotion to captain once a vacancy arose. Of course, it was entirely possible that once a captaincy became vacant, a lieutenant with the finances could purchase this over the head of the most senior lieutenant. Obviously, this ‘jumping the que’ method of advancement was not popular with those who were passed over. Alternatively, one could obtain promotion by means of volunteering to serve in a regiment going to an ‘unpopular’ posting such as the West Indies, which due to the climate was known as the ‘British soldiers’ graveyard’. Likewise, convict escort duty to the Australian Colonies could be a rapid means of promotion as some officers transferred out of the escorting regiment, thus creating vacancies.

Although against regulations, the asking prices for an ensigncy or lieutenancy went down in price so as to attract potential officers who lacked the financial backing to afford a commission in any other regiment. This would seem to have been the path taken by Lieutenant John Nagel who opted to serve in the unpopular East Indies. As Nagel had been born at Jaffna Patram on the Island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), the climate may not have affected him as much as an officer direct from Britain.

Free settlement at Moreton Bay

The role of the subaltern officer in Moreton Bay during the convict period changed with the beginning of the free settlement phase. It had been anticipated by both the Colonial and War Offices in Britain that with the end of transportation and the move towards a free settlement, the military would have no role and these troops could be returned to Britain or a colony that had greater need of them. The rationale for this became increasingly apparent as Britain’s post-Waterloo empire grew while her army remained the same size such that, by the 1830s, there were more redcoats posted overseas guarding British possessions than were actually stationed in Britain itself. As the Duke of Wellington observed, this imbalance meant that, in the event of a major European war, Britain would have to rely on its navy alone for defending the home isles.

By the 1840s Colonial Secretary Earl Grey introduced some reforms to alleviate this demand upon Britain’s army by dividing the British colonies into three categories. Some colonies were purely military in nature such as Gibraltar, while others such as India and South Africa still needed a strong military presence due to the on-going conflicts. The last category included colonies that were either self-governing or approaching this status, such as Canada and the Australian Colonies, which were intended to provide for their own defence. While it seemed reasonable that those colonies with self-governance should also look to their own defence, they objected to bearing the cost of protecting assets over which Britain held a trade monopoly.

Moreover, in the event of a major European war, these colonies would be vulnerable to foreign attack as a result of Britain’s foreign policies over which they had no control. Eventually a temporary compromise was reached between Britain and her semi-independent colonies which saw the continuation of redcoats posted to these colonies, until such time as they had their own viable volunteer defence forces. However, a combination of inter-colonial rivalry and hostilities in New Zealand necessitated the retention of British soldiers in the Australasian colonies far longer than anticipated.

Frontier Conflict

British soldiers remained at Moreton Bay as the frontier conflict with Aborigines in the early 1840s was seen as comparable to the Māori uprising in New Zealand. Roderick Flanagan in his Aborigines of Australia (1888) referred to this period as ‘The Rising of 1842-1844’ describing it as a ‘simultaneous aggressive movement of the aborigines throughout the entire colony and along its boundaries, which commenced in 1842, and continued… For more than two years. The warfare which the blacks waged upon the stations…was universal, implacable, and incessant’ (Flannagan, Aborigines of Australia, p.14). While the Moreton Bay penal station had been relatively isolated due to the fifty-mile exclusion zone surrounding it, occasional clashes with Aborigines occurred as early as Logan’s time when the settlement’s crops were raided. The scale of these skirmishes were relatively insignificant as the military’s attention was focussed inwards at the convict population, but with the winding down of Moreton Bay as a penal station, the role of the military with regard to the local Aborigines was to change dramatically with the coming of free settlement.

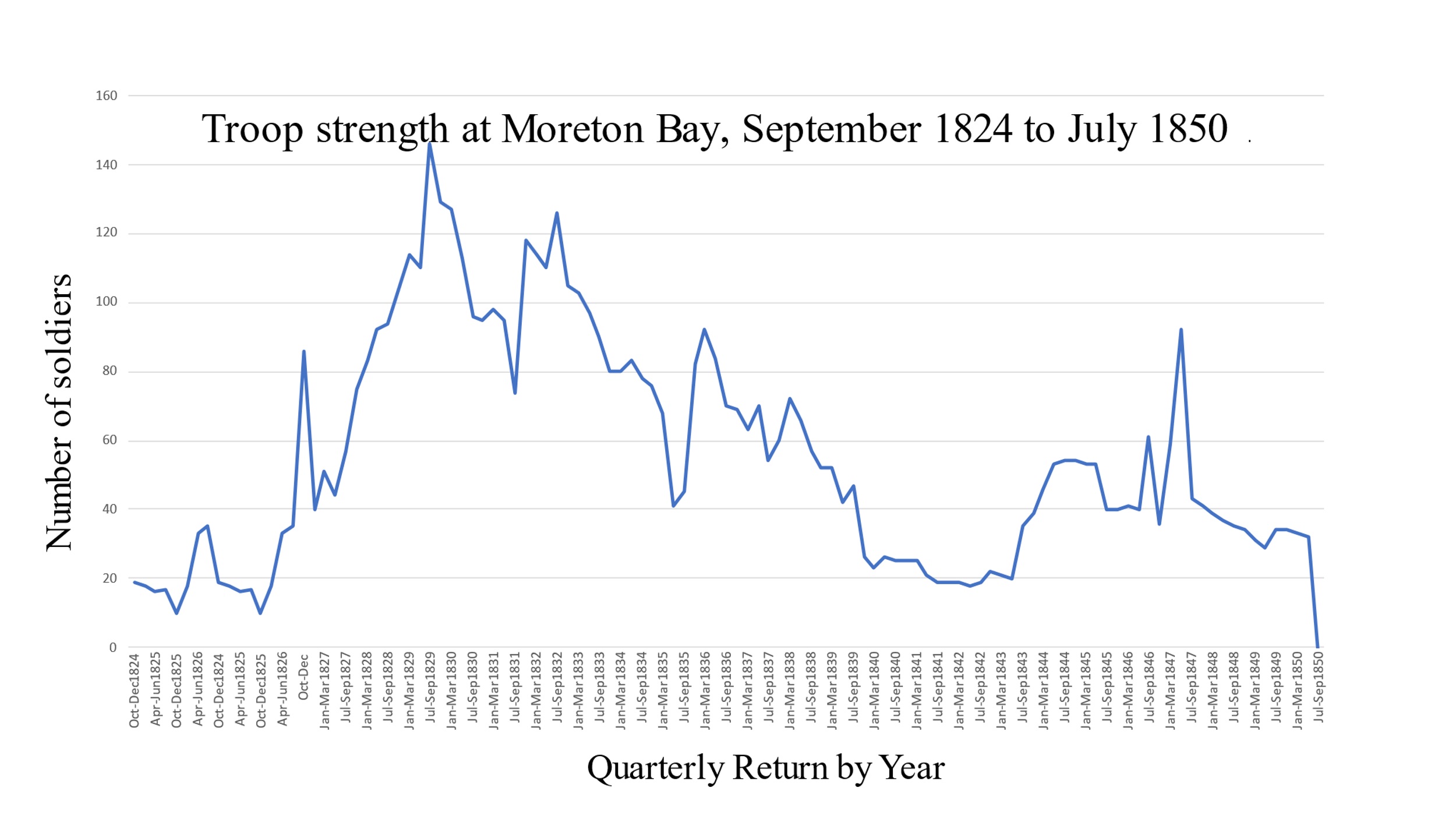

As the penal settlement at Moreton Bay wound down in preparation for becoming a free settlement, the military detachments sent to this posting correspondingly decreased in size over time, a trend which is apparent by glancing at the troop strength chart. As can be seen, there are two distinct humps with the first describing the rise and decline of the penal station with the end of transportation, while the second lesser hump, beginning in 1843 describes the rush to reinforce the military at Moreton Bay in light of the outbreak of Aboriginal conflict in the district. This outbreak of Indigenous resistance commencing in late 1842 and reaching its peak over the following two years, also caught the military by surprise and there can be little doubt that without the assistance of parties of well-armed mounted settlers and the rapid arrival of reinforcements from Sydney, these insignificant Brisbane detachments would have been entirely ineffective for the duties assigned them.

Gorman’s force of barely twenty soldiers of the 80th Regiment was replaced in May 1842 by a detachment of much the same size from the 99th Regiment commanded by Lt John James Armstrong, a 20 year old Irish subaltern who had received his lieutenancy only the month before. While Armstrong reported in a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald that ‘the blacks still continue troublesome about the Darling Downs, making it very unsafe travelling, unless in company and well-armed’ he was fortunate to have left the district before the frontier war reached its crescendo in 1843 under his successor, Lt Patrick Johnston. Johnston, as noted earlier, was the youngest subaltern to have served at Moreton Bay, although unlike Armstrong he had an extra 15 months experience as a lieutenant and would go on to gain considerable combat experience, as well as a few wounds, while serving in New Zealand.

The period of Johnston’s posting at Moreton Bay from late 1842 through to late 1846, and the end of Lt William Hobart Seymour’s command, saw an unprecedented slaughter of Aborigines. Bones were still being recovered from the site in the early 20th century.

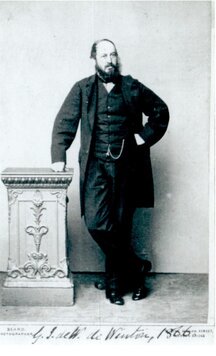

Even Lt George De Winton, writing from Brisbane the following year in 1847, noted of Johnston’s reign that he ‘impart[ed] severe lessons’ to the Aborigines. Likewise, J J Knight who wrote within living memory of these events asserted

This period of military supervision was one of terrible slaughter, scores upon scores of the aborigines falling victims to the white man’s gun. One of the men who assisted in putting many of the unfortunate blacks out of existence told the writer several incidents which if repeated here would scarcely be regarded as pleasant reading, nor yet redound to the credit of persons even now living (Moreton Bay Courier 25 April 1892, p2).

This embarrassing silence by white participants was not mere sentimentality, but also a means of avoiding punishment under the white man’s law. In a letter to the Maitland Mercury one correspondent declared ‘we were more successful in falling in with the blacks …, but I do not wish to say too much on that subject’ (Maitland Mercury, 18 November 1843 p.4).

There can be little doubt that this Aboriginal uprising was a concerted effort across SE Queensland and west across the Downs. Isolated stations were besieged, drays were ambushed, and station-hands fortified their homesteads with gun-slots and an arsenal of muskets. As many of these major squatters were also commissioned magistrates, they had the authority to call upon the military to act in aid of the civil authorities to restore order. Their guide in using this power was outlined for these magistrates in John Plunkett’s Australian Magistrate which was given to every newly appointed Justice of the Peace within NSW, and explained that not only could civilians be deputised to provide an armed force, but the military could also be commandeered to provide assistance to restore order. While this role would normally be filled by a frontier police force, none as yet existed beyond the few drunken and insubordinate Border Police troopers available to Commissioner of Crown Land Stephen Simpson. Consequently, these magistrate/squatters could lay claim to vast tracts of land and if any Aboriginal resistance was encountered, they could act within the letter of the law in calling out both a locally raised posse comitatus and the military to consolidate their land holdings, all under the guise of restoring order.

After a particularly vicious clash in September 1843 near the foot of the Downs known today as the Battle of One Tree Hill, Lt Johnston established a military post, often mistakenly called Fort Helidon, where a dozen redcoats (that is, half his entire force) were posted with orders to escort drays bound for the Downs. As can be seen by the troop strength graph, this met with a rapid reinforcement of troops sent from Sydney. The significance of this reinforcement is hard to over-state as elsewhere in the Australian Colonies troops were being withdrawn and sent across the Tasman to meet the Māori crisis in New Zealand. Hence, that the commander of British forces in the Australian colonies, Major-General Edward Wynyard could find the necessary troops to double the Moreton Bay detachments’ size at a time when every spare soldier was needed in New Zealand, says much about how seriously the Aboriginal uprising in the northern district was seen.

Frontier conflict continued after Johnston’s departure and was met with a force numbering over fifty soldiers commanded by Lt Charles Leigh of the 99th Regiment. He too was replaced in mid-1844 by detachments drawn from the 58th Regiment commanded by Capt William Grant, Lt Francis Master, Lt Edward Barker and Lt Isaac Cooper, who all went on to serve in New Zealand. By 1846 the conflict was beginning to abate and by the time of William Seymour’s posting that year, he recommended that Fort Helidon be closed down due to the difficulty of keeping it supplied and the decline of frontier violence. By the time of Seymour’s successors, Lt Charles Blamire (Sept 1846 to May 1847) and George De Winton (July 1847 to May 1848), Moreton Bay ceased to be a military post.

By 1848 and the withdrawal of Lieutenant William Seymour’s Brisbane detachment of the 99th Regiment, the military authorities felt there was little justification for retaining a military post at Brisbane. This removal of redcoats from Brisbane left the settlement unprotected for the first time since its founding and many local residents petitioned for the restoration of a military force:

May it please your Excellency,-The undersigned inhabitants of the town of Brisbane, Moreton Bay, beg respectfully to express to your Excellency their regret at the entire withdrawal of the military detachment that has hitherto served in this district, and to express their apprehensions of the result. They would suggest to your Excellency several circumstances which appear to them to give the inhabitants of this settlement a strong claim to the protection of a military force:-1st, The fact of their being surrounded by a numerous aboriginal population, who, though the latter have been little troublesome hitherto in the neighbourhood of the town, cannot but feel their comparative strength now that the force, of which they stood in great awe, is removed (Moreton Bay Courier 22 July 1848, p. 2)

As a consequence, the Commander-in-Chief of troops in the Australian Colonies, Major-General Edward Wynyard despatched a small detachment of 34 soldiers from the 11th Regiment commanded by 22 year old Ensign George Cameron. Cameron’s role as commanding officer of the Brisbane detachment was remarkable for two reasons; the first being that, as an ensign, he was the lowest ranking subaltern to ever be in command of a Brisbane detachment. The second precedent was that Cameron was the first commanding officer to not also hold a dual commission as a Justice of the Peace. As Lt De Winton noted in his memoirs, ‘the officer in command was always nominated as a magistrate’. This point may not have mattered but for an incident involving Aborigines in late 1849 when Cameron’s detachment mistakenly fired into a group conducting a night-time corroboree. Normally such civil disturbances were dealt with by a magistrate and a few constables, but none were immediately to hand that night. Had Cameron also held a dual commission as commanding officer as well as Justice of the Peace (as had all his military predecessors at Brisbane) he would have known what the law expected of him in such an emergency. As it was, the only available magistrate at that hour, Dr David Keith Ballow, flatly refused to become involved thus leaving Cameron to act independently without the guidance of any magistrate.

This incident became known as the Affray at Yorks Hollow and after a show trial conducted by Justice Therry to punish those soldiers believed to have fired without authorisation, the entire detachment was removed from Brisbane Town in July 1850 under a cloud of ignominy. As a consequence, the Moreton Bay district was, for the first time since its founding, devoid of any military force for the following decade until Governor Bowen’s arrival and his insistence for more Imperial troops in the form of the 12th Regiment detachment from 1860 to 1866, followed by a full company of the 50th Regiment from 1866 until its withdrawal in 1869. These would be the last British troops posted to Brisbane until a locally raised volunteer force was established with mixed success.

Conclusion and select bibliography

In conclusion it can be seen that the roles of the subaltern officers varied greatly in accordance with whether their service was during the convict or early free settlement phase of Moreton Bay’s early history. Subalterns serving during the convict period tended to have briefer postings and were always subordinate to the commandant. Whereas during the early free settlement period the subalterns invariably acted independently upon their own judgement with no superior to direct them, and as a consequence, mistakes were made. This was particularly the case during the settlement’s frontier war for which none of the subalterns were trained in this type of guerrilla conflict. Finally, throughout this early free settlement phase the size of the detachments were such that they could not hope to provide much more than psychological reassurance to settlers.

Select Bibliography

Books

De Winton, George Jean. Soldiering Fifty Years Ago: Australia in the Forties. Ludgate Circus: European Mail, (1898).

Flannagan, Roderick. The Aborigines of Australia. Sydney: Edward F. Flanagan and George Robertson and Co., (1888).

Kerkhove, Ray and Uhr, Frank. The Battle of One Tree Hill: The Aboriginal Resistance That Stunned Queensland, Boolarong Press, (2019).

Knight, John James. In the Early Days: History and Incidents of Pioneer Queensland. Brisbane, Qld: Sapsford & Co, (1898).

Petrie, Constance Campbell. Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland (Dating from 1837). Recorded by His Daughter. 1st ed. Brisbane, Qld: Watson, Ferguson & Co., (1904).

Plunkett, John Hubert. The Australian Magistrate; or, a Guide to the Duties of a Justice of Peace for the Colony of NSW: Also a Brief Summary of the Law of Landlord & Tenant. Sydney: James Tegg, (1840).

Shaw, Barry (ed.) Brisbane: The Aboriginal Presence 1824-1860. Second

ed, Brisbane History Group Papers No.11 2020. Tingalpa, Qld, 4173: Boolarong Press, (2020).

Journals

Pratt, Rod. ‘The Affray at York’s Hollow, November 1849’, Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal, Vol. 18, Issue 9, pp. 384-396, (Jan 2004).

Pratt, Rod and Hopkins-Wise, Jeff. ‘Redcoats in the 1840s Moreton Bay and New Zealand’, Queensland, Review, vol. 26, no. 1 (2019).

Stanley H. Palmer, ‘Calling out the Troops: The Military, the Law, and Public Order in

England, 1650-1850’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, vol. 56, (1978).

Newspapers

Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 1842, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12414052

Sydney Morning Herald, 17 December 1849, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12917206