Hannah Rigby – An Overview

Hannah Rigby is perhaps best known for being the only female convict to remain in Moreton Bay when the convict settlement closed. She is also notorious for receiving three separate sentences of transportation: one from England to New South Wales, and twice to Moreton Bay for crimes she committed in the colony; she was one of only three women to be sent to the dreaded penal settlement at Moreton Bay twice.

Hannah was a seamstress and embroiderer from Liverpool who was convicted of larceny in October 1821 and sentenced to seven years’ transportation to New South Wales. She arrived in Sydney on the Lord Sidmouth in February 1823. Hannah married ticket-of-leave man George Page in 1825, probably in the notorious marriage market of the Parramatta Female Factory. Their married life together was cut short the following year when Page was found guilty of stealing and sentenced to transportation to Moreton Bay. When Hannah’s first sentence expired, she re-offended in Newcastle and was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to Moreton Bay. After that sentence expired and she was returned to Sydney, she immediately offended again and was sent back to Moreton Bay for a second time. After her arrival in the colony she bore three sons: the first in 1824 to a government clerk in Sydney, the second in 1828 to an unknown father, and the third in 1832 to the boat pilot at Moreton Bay. Another son has recently been discovered, born in Liverpool before Hannah’s transportation. Having gained her freedom in 1840, Hannah remained in Brisbane until her death in 1853. Even the manner of her death is notable: Hannah died suddenly the day after a wedding in which she had “participated in the cheer” perhaps too enthusiastically.

![MHNSW - StAC: NRS-905 [4/2499.2] Letter no 39/13197 enclosing 40/8432, Hannah Rigby](https://harrygentle.griffith.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/rsz_ballows_letter_page_1-195x300.jpg)

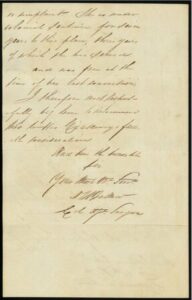

Although she had repeatedly transgressed against the law and Victorian standards of “moral” behaviour, as an assigned convict servant Hannah won the esteem of her employer, the very respectable Dr David Keith Ballow, who praised her warmly when advocating for her freedom. Hannah was, he said, an “exemplary” servant who had never given him “the slightest cause for distrust or complaint”. This impression of the model servant conflicts intriguingly with that of the recalcitrant, intemperate thief.

So who really was Hannah Rigby? Hannah was a serial haberdashery thief, a prisoner, an “exemplary” servant – and a single mother determined to keep her family together. She was exiled from her home and disappointed by a series of men. She was a woman of remarkable strength and character who, despite a lifetime of suffering and loss, remained fond of a “lark” to the end. These pages set out some of the milestones and important relationships in the story of the convict Hannah Rigby.

Jane Smith, Visiting Fellow 2024, HGRC

Jane Smith is a librarian, archivist, freelance book editor and author. She holds a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Queensland, a Graduate Diploma in Applied Science (Library and Information Management) from Charles Sturt University, and a Graduate Certificate in Editing and Publishing from the University of Southern Queensland.

Jane enjoys bringing history to life through fiction and non-fiction for all ages. She has written more than twenty books with a history focus. Her book Ship of Death: The Tragedy of the “Emigrant”, which tells the true story of the 1850 voyage and quarantine of the typhus-stricken ship Emigrant, was shortlisted for the 2021 Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize. Three of Jane’s children’s books have also been shortlisted for literary prizes. More about the author and her books can be found here.

Jane’s biography of Hannah Rigby was published in March 2025 by Big Sky Publishing as One Free Woman: The Unstoppable Convict Hannah Rigby.

Hannah Rigby – A Timeline

| Date | Event | Source | |

| 1794? | Hannah Rigby is born in Liverpool. | MHNSW-StAC. Butts of Certificates of Freedom, Hannah Rigby. NRS 12210, Reel 983, no.28/1001. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

| 1815

|

26 Jan | Hannah’s son is born.

|

Lancashire Archives, England. Liverpool. Order of filiation and maintenance of bastard son of Joseph Barrow of Sutton, comb-maker, and Hannah Rigby, singlewoman, QSP/2680/89, 8 Mar 1815. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

also Lancashire Archives, England. Lancashire Courts of Quarter Sessions – 1583-1999, Order Book, QSO/2/184, p.260. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

| 8 March | Hannah faces the churchwardens and overseers of the poor to seek maintenance from her son’s father, the comb-maker Joseph Barrow of Sutton near St Helen’s.

|

||

| 1818

|

19 Jan | Hannah is convicted of larceny at the Liverpool Borough Sessions and imprisoned for 3 months, possibly at the Liverpool County House of Correction. | National Archives, Kew. Home Office: Criminal Registers, England and Wales, Class HO 27, Piece 15, p.297. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

And

Lancashire Archives, England. Quarter Sessions Recognizance Rolls, QSB/1/1818, January Part 5. |

| 20 April

|

Hannah is convicted of larceny at the Liverpool Borough Sessions. Charged with Esther Cashell and imprisoned for 1 year at Preston Gaol. The crime was committed against Henry Hunt, a linen draper at 8 Church St. | Lancashire Archives, England. Quarter Sessions Recognizance Rolls, QSB/1/1818 April Part 4.

|

|

| 1819

|

24 May | Hannah is committed for trial for stealing one ornamental feather from John Jones.

|

National Archives, Kew. Liverpool Gaol, Lancashire: Calendars of Trials at Liverpool Borough Sessions, Series PCOM2, Piece 330. Accessed via FindMyPast. |

| July | Hannah is tried in Liverpool for the above crime and sentenced to 2 years at Preston Gaol. | National Archives, Kew. Home Office: Criminal Registers, England and Wales, 1805-1892. Series HO27, Piece 17, 1819. Accessed via FindMyPast. | |

| 1821

|

2 Oct | Hannah is tried for larceny at the Quarter Sessions at Liverpool. She is tried with 18-year-old Elizabeth Leigh. They are accused of stealing 2 caps from Hannah Robinson and 28 yards of cotton print from John Dawbarn.

Elizabeth is sentenced to 3 months’ imprisonment, but Hannah is sentenced to 7 years’ transportation to NSW.

Hannah is held at the Kirkdale County House of Correction while she waits to be transported. |

Lancashire Archives, England. Quarter Sessions Recognizance Rolls, QSB/1/1821 Oct Part 7.

And

National Archives, Kew. Home Office and Prison Commission: Prisons Records, Series 1. Liverpool Gaol, Lancashire: Calendars of Trials At Liverpool Borough Sessions, PCOM 2/330. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

|

| 1822 | Aug – possibly 22 | Hannah boards the ship Lord Sidmouth at Woolwich with:

· Captain Ferrier · Surgeon Robert Espie · Clergyman Rev. Henry Williams · 97 convict women with 23 children · 21 free women with 49 children. |

Details of the voyage can be found at:

The National Archives; Kew, England. Surgeon’s Journal of Her Majesty’s Female Convict Ship Lord Sidmouth, Mr Robert Espie, Surgeon, from 22 August 1822 to 1 March 1823, ADM 101/44/10, accessed via https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/docs/ships/LordSidmouth1823_SJ.pdf

List of convicts on board can be found at:

The National Archives, Kew, England. Convicts Transported, HO 11/4. Accessed via Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/70503:1180 and MHNSW-StAC. Musters and Other Papers Relating to Convict Ships, NRS 1155, Reel 2424, p.331. Accessed via Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/49184:1211 |

| 11 Sept | Lord Sidmouth sets sail. It travels from Woolwich down the Thames to Gravesend, Margate, Toreland, Dungeness and Torbay, and loses sight of England finally on 19 Sept. | Details of the voyage can be found in Robert Espie’s Surgeon’s Journal as above, and in:

ATL, Wellington, NZ. Henry Williams, Letters to the Church Missionary Society from Henry Williams, vol.1 (1822-1830), Typed transcript (1940), Ref.qMS-2230. And ATL, Wellington, NZ. Henry Williams, Mrs Marianne Williams and Mrs Jane Williams, Letters and Journals Written by Rev Henry and Mrs Marianne Williams and the Rev and Mrs Jane Williams, Vol. 1 & 2 (1822-1828), Typed transcript (1936), Ref. qMS-2225. |

|

| 1823 | 27 Feb | Lord Sidmouth arrives at Sydney Cove. | Surgeon’s Journal as above. |

| 1 March | A government boat takes the convict women from Lord Sidmouth up the river to Parramatta. | Surgeon’s Journal as above. | |

| Around Sept | Hannah has a relationship with government clerk Robert Crawford, who had come free in the Royal George in 1821. | “Robert Rigby” Baptism of Robert Frederick Rigby, Baptisms, 1790-1825, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, 12 Dec 1824, Ref. no. REG/COMP/1, Vol 01. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

| 1824 | 6 June | In Parramatta Hannah has a son, Robert Frederick, fathered by Robert Crawford. | “Robert Rigby” Baptism of Robert Frederick Rigby as above. |

| Late Sept | Muster of 1824 shows Hannah at the Parramatta Female Factory with one son, aged 3 months. | MHNSW-StAC. District Constables’ Notebooks, Parramatta, 1824 (Book 5), O-S, NRS 1263, Reel 1254.

Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

|

| 7 Dec | Hannah requests permission to marry ticket-of-leave man George Page. | MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Index to the Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825, Reel 6014, [4/3513]. Accessed online at https://search.records.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX2482177. | |

| 12 Dec | Robert Frederick Rigby, son of Hannah Rigby and Robert Crawford, is baptised at St John’s Anglican Church in Parramatta. | “Robert Rigby” Baptism of Robert Frederick Rigby as above. | |

| 1825 | 3 Jan | Hannah Rigby marries George Page at St John’s Church of England, Parramatta, with Rev Marsden officiating. | “George Page and Hannah Rigby” 1825, Marriage Certificate of George Page and Hannah Rigby, 3 Jan 1825, certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg. no. 3471/1825 V18253471 3B. |

| Late Sept | Muster of 1825 shows Hannah employed as general servant to George Page. | National Archives, Kew. Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, Class HO 10, Piece 20. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

| 27 March | Robert “Crawford”, son of Hannah and Robert Crawford, is baptised at St Philip’s church in Sydney. | “Robert Crawford”, Baptism of Robert Crawford, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg no. 824/1824 V1824824 8. | |

| 1826

|

4 May | George Page receives his certificate of freedom. | MHNSW-StAC. Registers of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 12208, Reel 602, Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

| 26 May | George Page is arrested. A woman (Elizabeth Johnson) had been seen wearing a dress made from fabric that had been stolen from Mr Charlton, the master of the Lord Rodney, in December 1825. When questioned, she said she had bought the fabric from George Page. His house was searched and more of the fabric is found, some of it made up into dresses and curtains. Page admits he had sold the fabric to the woman but his accounts of how he came by it are inconsistent. He is committed for trial. | “The Police,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, May 31, 1826, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2185885. | |

| 10 June | George Page is indicted for stealing primed cotton, the property of Mr John Charlton, Master of the brig Lord Rodney, in December 1825. | “Supreme Criminal Court,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 14, 1826, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2185981. | |

| 19 June | George Page is tried for a grand larceny and found guilty of stealing fabric from a ship and sentenced to 7 years’ transportation.

|

MHNSW-StAC. George Page, Criminal Court Records Index 1788-1833, 13477 [T23] 26/89, 10/06/1826.

and “Supreme Criminal Court,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 21, 1826, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2186010. |

|

| 13 July | Hannah writes to the governor from Sydney Gaol, saying she was “now bereft of every support for herself and child” and asking to be sent “with her husband to whatever penal settlement your Excellency may appoint”.

Her petition is approved, but for some reason she does not go. It appears that she is re-assigned as a servant. |

MHNSW-StAC. Petitions from Wives of Convicts,

1826-1827, NRS 906-1, Volume 4/7084. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

|

| Late August | Hannah absconds from service. She is at large for about 2 weeks. | MHNSW-StAC. Entrance Books [Sydney Gaol], NRS 2514, 4/6429, Reel 850, p.85.

MHNSW-StAC. Entrance books [Sydney Gaol], NRS 2514, Item 4/6430, Reel 851. Accessed via Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/65395:1783. |

|

| Hannah took her son (Robert) with her when she absconded. Record states: “Hannah Rigby & child – Lord Sidmouth – Illegally at large in Sydney. | MHNSW-StAC. NRS-897, Main series of letters received

[Colonial Secretary], [4/1791], Reel 702, p.268. |

||

| 1 Sept | George Page is transferred from Phoenix to Amity for transportation to Moreton Bay. | Australian, September 26, 1826, 2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/37071777/4248905. | |

| 7 Sept | Hannah is admitted to Sydney Gaol for being “illegally at large”. | MHNSW-StAC. Entrance Books [Sydney Gaol], NRS 2514, 4/6429, Reel 850, p.85.

MHNSW-StAC. Entrance books [Sydney Gaol], NRS 2514, Item 4/6430, Reel 851. Accessed via Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/65395:1783. |

|

| 8 Sept | Hannah is discharged to the Parramatta Female Factory for 3 months. | MHNSW-StAC. Entrance Books [Sydney Gaol], NRS 2514, 4/6429, Reel 850, p.85. | |

| 22 Sept | George Page arrives at Moreton Bay on the Amity. | SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.1, letter [4/1917.1], pp.320-324. | |

| 1828

|

July or August | Hannah’s son Samuel is born. | MHNSW-StAC. 1828 Census: Alphabetical Return, NRS 1272; Reel 2555. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

| Nov | Muster of 1828 shows that Hannah is in Newcastle, living as a “sempstress” with her 5-year-old son Robert and her 3-month-old son Samuel. She gives her age as 29. | MHNSW-StAC. 1828 Census: Alphabetical Return, NRS 1272; Reel 2555. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

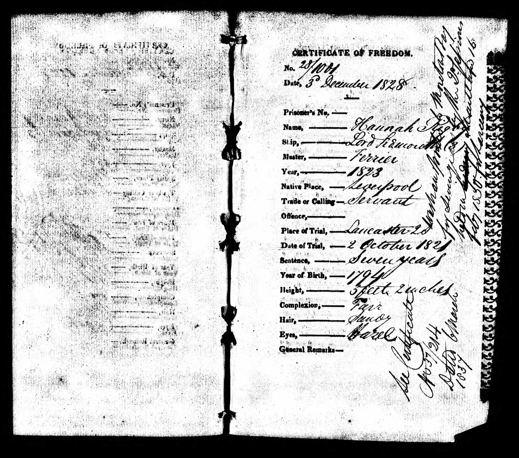

| 3 Dec | Hannah receives her certificate of freedom. | MHNSW-StAC. Butts of Certificates of Freedom, Hannah Rigby. NRS 12210, Reel 983, no.28/1001. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

| 1829 | 13 or 14 Nov | Hannah steals ribbons from Frederick Boucher’s shop in Newcastle. She is found with the ribbons at the home of Robert Young. She is arrested along with Young’s 17-year-old daughter, Mary Anne Young. | MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Quarter Sessions Cases 1824-1837. Item No: [4/8402], Reel 2405, p.67, Entry 4, 1830. |

| 1830 | 16 Feb | Hannah appears at the Maitland Quarter Sessions, charged with stealing with force and arms thirty yards of ribbon valued at £1 belonging to Frederick Boucher. She is found guilty and sentenced to transportation to a penal settlement for 7 years. | MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Quarter Sessions Cases as above. |

| 17 March | Hannah is sent from Newcastle to Sydney Gaol on the cutter Lord Liverpool with her two young sons (Robert, 6 years and Samuel, 1). | MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Index to Colonial Secretary Letters Received [4/2070], Letter no.

30/2382. |

|

| 30 May | Samuel is christened at St Philips in Sydney. Hannah gives his father’s identity as “Samuel Rigby, clerk” and his age incorrectly as almost 17 months (5 or 6 months younger than he really was). | “Samuel Rigby”, Baptism of Samuel Rigby, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg no. 186/1830 V1830186 14. | |

| 16 Oct | Hannah boards the Isabella with 7 other female convicts, bound for Moreton Bay. The women are:

· Hannah Rigby · Maria Bennet (Boyce) · Mary Ann Gallagher · Mary Browne · Mary Connors · Mary Courtney (Gazzard) · Ann Spinks · Margaret Sullivan (aka Somers/Summers). |

QSA. Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay, ITM869689, digital file DR23432. | |

| 1 Nov | Hannah arrives in Moreton Bay on the Isabella.

[Capt Logan has just been murdered] |

||

| 1831 | 2 Feb | Hannah is admitted to the convict hospital with intermittent fever (probably malaria). She is treated with Ligare arsenic, minim (unit of volume – a drop) aqua (in water) 3 times in a day, and lime juice, mimosa and reduced rations. Samuel is treated with fever at the same time. Hannah is discharged on 28 Feb. | QSA. Register of cases and treatment – Moreton Bay Hospital, 1830–1831, ITM2895 and ITM2858.

DR24197 (ITM2895 part 1, folio 33 & 21) shows Hannah being admitted 2 Feb 1831. DR24192 (ITM2858 part 3) shows Samuel being treated with fever on 2 Feb 1831.

See also DR24200. |

| 1832 | 27 Sept | James Rigby, son of Hannah (registered as unmarried) is born. His father is unnamed in the register of births (though James’s 1914 death certificate identifies his father as the boat pilot, James Hexton. By then Hannah’s son was going by the name James Hexton). | QSA. Book of half-yearly returns of baptisms at the Moreton Bay penal settlement 1832-1835, ITM869685. |

| 26 Oct | Hannah is admitted to Moreton Bay Hospital again with intermittent fever, and discharged on 29 Oct. | QSA. Register of provisions, patients and medicines for the Moreton Bay Hospital, ITM2891 (Part 1, DR24175). | |

| 1837

|

13 Feb | At the expiration of her sentence, Hannah is sent back to Sydney on the Governor Phillip.

Her two older sons must have been with her. |

SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.9, letter [37/2193], pp.489-490. |

| 6 March | Hannah receives her ticket of freedom. Her certificate indicated she is the wife of George Page, but no evidence has been found to suggest that she re-joins him. | MHNSW-StAC. Butts of Certificates of Freedom, Hannah Rigby. NRS 12210, Reel 998, no. 37/214. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, 22 April 1837, p.4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2210540. |

|

| 11 June | Mr Templeton of Castlereagh Street sees two children wearing caps made of materials that had been stolen from his premises; he finds that the mother of the children is “Ann” Rigby, whom he had employed in his shop. She is committed for trial, but allowed out on bail. | Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 13, 1837, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2211393. | |

| 23 June | “Mary” Rigby, goes into the shop of Mr Maelzer in George-Street, and steals a piece of drill (or perhaps fustian); she is arrested, and the property is found upon her person. A child is in her company at the time, wearing a new blue cloth cap with a silver lace band, and tassel. Suspicious, the constable removes it, and underneath discovers a cap “more suited to the rest of the attire”. Rigby claims she had purchased the cap for a dollar, but the constable makes enquiries at various shops and finds it had been stolen from Mr Russell, the hatter. | Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 27, 1837, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2211631.

|

|

| The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported that the woman who had stolen the fabric from Mr Templeton on 11 June was the same woman who stole the drill from Mr Maelzer and the cap from Mr Russell on 23 June. This time she was refused bail. | Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 29, 1837, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2211661. | ||

| 27 or 28 Oct | Hannah is returned to Moreton Bay on the Isabella.

On board with her are: · Ellen Doyle, · Ann Hughes, · Margaret McCann, · Elizabeth Payne (Hyland) · Elizabeth Standley. Her sons Robert and Samuel are not with her. |

Letter to the Col sec suggests they are to leave on 27 Oct:

SLQ. Copies of Letters Sent to the Sheriff 1828-1851, Reel AO 1064, letter 37/300, p.254.

Newspaper article says they set off on 28 Oct: The Australian, 31 Oct 1837, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/36855325. |

|

| Nov | The women arrive in Moreton Bay. They take the numbers of female prisoners up to the largest ever housed there: 92 | Jennifer Harrison, Shackled: Female Convicts at Moreton Bay 1826-1839 (Melbourne: Anchor Books Australia, 2016), p.34. | |

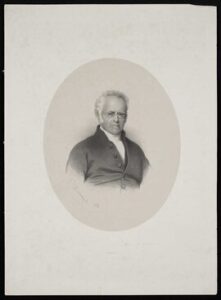

| 1838 | March | Dr Ballow travels to Moreton Bay. | The Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, 22 March 1838, p.2. |

| June | Hannah is one of about 75 female convicts in Moreton Bay, with a report “conduct good, but ineligible for first class, not having been one year in the factory”. | SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.10, letter [38/6900], p.89-96. | |

| 1839 | From March | The penal settlement at Moreton Bay is wound down. From about March 1839, convicts are gradually evacuated | Jennifer Harrison, Shackled: Female Convicts at Moreton Bay 1826-1839 (Melbourne: Anchor Books Australia, 2016). |

| Nov | Hannah is a servant to Dr Ballow, and one of only 5 convict women in private service. | MHNSW-StAC. Lists of Prisoners at Moreton Bay, 1839; Volume: 4/2460. Accessed via Ancestry.com | |

| 1840 | March | Hannah is still in private service to Dr Ballow in Moreton Bay, and is the only female convict left there. | MHNSW-StAC. Lists of Prisoners at Moreton Bay, 1840; Volume: 4/2499. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

| 1840 | 4 July | Dr Ballow requests the commandant Lieutenant Owen Gorman to petition for a remission of sentence for her, indicating that her conduct had been exemplary and she had never given him any cause for distrust or complaint. In the letter, he says she has worked for him “upwards of 12 months”. | SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.11, letter [40/8432], pp.234-237. |

| 2 Sept | Hannah’s sentence is remitted. | MHNSW-StAC. Colonial Secretarial Register of Sentences Remitted, 1838-1841; Volume: 4/4544. Accessed via Ancestry.com. | |

| 1845 | 22 August | Robert Rigby/Crawford is granted permission to marry. | MHNSW-StAC. Convicts Applications to Marry 1825-1851, CRAWFORD, Robert; alias RIGLEY, Robert KAY, Mary, NRS 12212 [4/4514 p.101], COD 15, Reel 715, Fiche 800-802. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

| 2 Sept | Robert Rigby/Crawford marries Mary Kay. | “Robert Crawford and Mary Kay” 1845, Marriage certificate of Robert Crawford and Mary Kay, 2 Sept 1845, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, No.533, Vol.77. | |

| 1846 | 15 Jan | Hannah puts a notice in the SMH indicating she is looking for Samuel and believes him to be “in the interior”. The letter suggests she is living in Sydney – perhaps as a servant at Mrs Cousens’s “Establishment For Young Ladies” that was at the stated address. | “Samuel Rigby,” Sydney Morning Herald, January 15, 1846, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/12884692. |

| 1847 | August | Mr Samuel Rigby on passenger list of the Tamar, sailing from Sydney to Moreton Bay, departed 10 Aug and arrived 15 Aug. | “Departures,” Sydney Chronicle, August 11, 1847, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31752917.

“Shipping Intelligence,” Moreton Bay Courier, August 21, 1847, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3713780. |

| 1850 | Sept | Dr Ballow dies. | Jane Smith, Ship of Death: The Tragedy of the “Emigrant” (Carindale, QLD: Independent Ink, 2019). |

| 1851 | 15 April | Boat pilot James Hexton drowns. | “Melancholy Accident,” Melbourne Daily News, April 30, 1851, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226519565

SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.22, letter [51/4382], pp.189-193.

“Death of Mr Hexton the Pilot,” Empire, April 22, 1851, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/60034287. |

| Hannah is living alone in a hut near Queen Street. | “Sudden Death,” Moreton Bay Courier, October 15, 1853, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3716200. | ||

| 1852 | 8 Nov | Son Robert Rigby dies in Sydney? | “Robert Rigby” 1852, Death Certificate of Robert Rigby, 8 Nov 1852, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg. no. 599/1852 V1852599 110. |

| 1853

|

7 Feb | Son Samuel Rigby dies in Brisbane? | “Samuel Rigby” 1853, Death Certificate of Samuel Rigby, 7 Feb 1853, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg. no. 1797/1853 V18531797 39B. |

| 11 Oct | Hannah dies the day after she “participated in the cheer” at a wedding. An inquest is held on 12 Oct and it is concluded that she died from natural causes and intemperance. | “Sudden Death,” Moreton Bay Courier, October 15, 1853, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3716200.

And

MHNSW-StAC. Registers of Coroners’ Inquests and Magisterial Inquiries, NRS 343, Reel 2921, Item 4/6613. Accessed via Ancestry.com. |

|

| 1914 | 12 Feb | Hannah’s son James Hexton dies in Brisbane Hospital. | Death Certificate Image, James Hexton, Registration no. 1914/B/18964, QLD Govt Family History Research Service.

“Passing of a Pioneer,” Truth, February 22, 1914, p.4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202668845 and “The Oldest White Native,” Brisbane Courier, February 18, 1914, p.5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/19949902. |

Introduction

Hannah Rigby, sentenced in October 1821 to transportation for seven years for larceny, sailed from England to New South Wales on the convict vessel Lord Sidmouth. The ship departed from Woolwich in September 1822 and arrived in Sydney in February 1823. This page provides some details about the voyage.

In brief

Captain: James Ferrier

Surgeon-superintendent: Robert Espie

Clergyman: Reverend Henry Williams of the Church Missionary Society (sailing with his wife Marianne and their three children)

Number of convict women: 97

Number of children of convict women: 23

Number of free women: 21

Number of children of free women: 49

Deaths:

- Mary McGowan (convict from Liverpool, aged 50)

- ? Edwards (18-month-old twin)

- Martha Edwards (18-month-old twin)

- Robert Borsch (10 years old).

The convict women

A list of the convict women on the voyage has been transcribed and is available online at:

Uebel, Lesley, and Hawkesbury on the Net. “Details for the Ship Lord Sidmouth (3) (1823).” Claim a Convict. https://www.hawkesbury.net.au/claimaconvict/shipDetails.php?shipId=256.

The list can also be found in the ship’s muster, which is accessible via Ancestry.com, from the following original sources:

MHNSW-StAC. Musters and Other Papers Relating to Convict Ships, NRS 1155, Reel 2424, p.331. Accessed via Ancestry.com. Muster of Lord Sidmouth.

National Archives, Kew, England. Convicts Transported, HO11/4. Accessed via Ancestry.com. List of convicts on board the Lord Sidmouth.

Timeline

A fuller account of the voyage can be found in the surgeon’s journal and in the letters and journals of Rev Henry and Mrs Marianne Williams. These sources make frequent mention of seasickness, which plagued the women for the duration of the voyage. The surgeon’s log also details the various misdemeanours the convicts committed, the punishments he inflicted and the rations he doled out. He provides detailed accounts of the illnesses and treatments of some of his patients whose conditions were troublesome.

Baugniet, Charles, 1854. Rev. Henry Williams. Ref: C-020-005. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Some of the milestones and events of the voyage are listed below.

| 22 Aug 1822 | The first groups of convict women embarked at Woolwich – a group from Maidstone Gaol and another from Liverpool. Over the following weeks, more groups of prisoners embarked each day. |

| 24 Aug 1822 | The Quaker Elizabeth Pryor visited the women and distributed haberdashery and other “useful articles” among them. |

| 26 Aug 1822 | Mrs Pryor visited again, with more useful articles like aprons. |

| 31 Aug 1822 | Mrs Pryor and Mrs Coventry visited, issuing articles and advice. |

| 5 Sept 1822 | Mrs Pryor visited again. |

| 6 Sept 1822 | Mr Capper of the Secretary of States office inspected the ship and was “highly pleased” with the vessel and the regulations.

J.T. Bigge, the late Commissioner to NSW, also visited. |

| 7 Sept 1822 | Mrs Pryor visited and gave out patchwork etc. |

| 8 Sept 1822 | The first punishment: Mary Turner was handcuffed for the day for violent and abusive conduct in the prison after dark the previous night.

Rev Dr Marsh visited and conducted divine service. Mrs Pryor and two gentlemen from the Missionary Society came on board and gave a Bible to each convict woman. Mrs Pryor made a speech to the women that was “extremely appropriate and affecting”. |

| 10 Sept 1822 | Handcuffed Ann Bolland for violent and abusive language. |

| 11 Sept 1822 | Rev. Williams and his wife and three children boarded.

In the evening, Ferrier received sailing orders and proceeded down the river to Gallions, a short distance away. |

| 12 Sept 1822 | The vessel proceeded down the Thames to Gravesend. |

| 14 Sept 1822 | Reached Queen’s Channel. |

| 15 Sept 1822 | Reached Margate. |

| 16 Sept 1822 | Reached So(uth?) Toreland.

Espie handcuffed Ann Jackson and Ann Bell for violent and abusive conduct and put them into the coal hole several hours. |

| 17 Sept 1822 | Reached Dungeness. |

| 18 Sept 1822 | Sailed south to Torbay.

Espie punished Ann Billings for stealing from her messmates by shaving her head. |

| 19 Sept 1822 | Lord Sidmouth was off Ushant. |

| 27 Sept 1822 | Espie punished Mary Heather and Deborah Saunders by putting them in solitary confinement in the coal hole for 24 hours, Mary for “indolence accompanied with insolence” and Deborah “for insolence to the chief officer”. |

| 30 Sept 1822 | Espie handed out the patchwork given by the Quakers. Rev. Williams began a school for the children, assisted by two of the free women. |

| 2 Oct 1822 | A female child, surname Edwards, an 18-month-old twin, daughter of a free woman, died from “Tabes” (wasting).

Ship was close to the Isle of Palma. |

| 3 Oct 1822 | Espie put Jane Gordon into the coal hole for “making a disturbance yesterday evening while the clergyman was at prayers”. |

| 8 Oct 1822 | Espie put Charlotte King into the coal hole for “violent and abusive conduct last night after dark in the prison”. |

| 9 Oct 1822 | Passed Cape Verde Islands 9 am. |

| 14 Oct 1822 | Weather very hot and the ship was nearly becalmed.

The other Edwards twin (Martha) died. Espie handcuffed Elizabeth Kinsey and Mary Brown together and put them into the coal hole for “abusive and mutinous conduct, and disturbing the peace of the ship”. |

| 20 Oct 1822 | Handcuffed a convict named Elizabeth Simpson for thieving. |

| 21 Oct 1822 | Shaved Elizabeth Simpson’s head. |

| 2 Nov 1822 | Espie punished Ann Crompton by putting her in solitary confinement in the coal hole for violence and disorderly behaviour towards her messmates. |

| 16 Nov 1822 | Espie punished Ann Gill by putting her into the coal hole for 8 hours “for insolence and refusing to make clean the part of the prison where she sleeps”. |

| 17 Nov 1822 | Passed Cape Frio at 8am.

Came to anchor at Rio de Janeiro Harbour at 5 pm. |

| 19 Nov 1822 | Mary McGowan, who had been ill and under treatment for some weeks, died. Next day she was taken ashore for burial. |

| 22 Nov 1822 | Espie “punished Rachel Davis and Elizabeth Hartnell by shaving their heads for boisterous and outrageous conduct yesterday afternoon”. |

| 29 Nov 1822 | After being delayed for a week due to the scarcity of water, the “watering” of the ship was finally completed: “a tedious, expensive, and laborious job”. |

| 30 Nov 1822 | Several women complained to Espie that they had not received their usual provisions; he investigated and found that the ship’s steward had been siphoning them off (probably to sell on shore). Espie refused to let the ship sail again until the steward is punished. |

| 2 Dec 1822 | Captain Ferrier finally agreed to dismiss the steward. |

| 3 Dec 1822 | Lord Sidmouth left Rio de Janeiro. |

| 18 Dec 1822 | Espie handcuffed together Sarah Bolland and Ann Gill “for violence and bad conduct last night after the doors of the prison were locked”. |

| 19 Dec 1822 | At daylight made the Island of Tristan D’Cunha. |

| 21 Dec 1822 | A boy named Robert Borsch aged about 10 years fell overboard off the bow sprit while playing with some other children. The accident was not discovered for at least 20 minutes, by which time he had disappeared. A service was held the next day. |

| 1 Jan 1823 | Espie discovered that Mary Scott, who had been employed as servant to the missionary, has been stealing. He shaved her head and separated her from the other women for some time. |

| 8 Jan 1823 | Espie punished Martha Ashley by handcuffing her for violent abusive conduct and for threatening him. |

| 9 Jan 1823 | Espie punished Elizabeth Capps with confinement in the coal hole all day for violence and abusive language. |

| 13 Jan 1823 | Espie handcuffed together Sarah Bolland and Elizabeth Warden for fighting the previous evening. |

| 18 Jan 1823 | Espie caught Ann Simmons stealing from one of her messmates and punished her by shaving her head. |

| 20 Jan 1823 | According to Rev Williams’s account, he, Captain Ferrier and Dr Espie went ashore to St Paul Island to do some fishing and hunting. |

| 22 Jan 1823 | Espie punished Sarah Phillips and Ann Gill with confinement in the coal hole for riotous behaviour the previous night after dark in the prison. |

| 23 Jan 1823 | Espie “confined Sarah Phillips and Ann Gill in the Coal Hole again for having said last night after I released them they did not value me, with many their hard words of indecorous meaning”. |

| 24 Jan 1823 | The ship’s boatswain hit one of the women for insolence. Espie felt the woman did not “possess her right faculties”; he dealt with the incident and determined to prevent it from happening again. |

| 30 Jan 1823 | Espie shaved Elizabeth Travis’s head for stealing. |

| 9 Feb 1823 | Entered D’Entrecasteaux’s Channel. |

| 10 Feb 1823 | Sailed up the River Derwent to Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land. Some of the free women whose husbands were at hand disembarked. |

| 12 Feb 1823 | Lieutenant Governor Sorell paid a visit to the ship and inspected it. “He

express’d himself highly pleased with appearance of the women and the arrangements I had carried into effect during the voyage.” More of the free women disembarked. |

| 13 Feb 1823 | 46 of the convicts were taken off the ship and sent to “respectable services”. |

| 15 Feb 1823 | All but two of the free women had found their husbands. |

| 19 Feb 1823 | Lord Sidmouth proceeded back down the River Derwent. |

| 24 Feb 1823 | Passed Cape Howe. |

| 26 Feb 1823 | Anchored off Jarvis Bay. |

| 27 Feb 1823 | Anchored in Sydney Cove a little after 8 am. |

| 28 Feb 1823 | The colonial secretary, Major Goulburn, came aboard and compiled the muster. |

| 1 March 1823 | The government boats arrived at 7 am and took the women and their luggage up the river to Parramatta. |

Sources

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. Henry Williams, Letters to the Church Missionary Society from Henry Williams, vol.1 (1822-1830), Typed transcript (1940), Ref.qMS-2230. Volume 1 contains letters written 1822-1830, transcribed in 1940.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. Henry Williams, Mrs Marianne Williams and Mrs Jane Williams, Letters and Journals Written by Rev Henry and Mrs Marianne Williams and the Rev and Mrs Jane Williams, Vol. 1 & 2 (1822-1828), Typed transcript (1936), Ref. qMS-2225.

Carleton, Hugh. The Life of Henry Williams. Vol. 1. 1874. Auckland: Upton. Accessed March 13, 2023. http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=1040&page=0&action=null.

Female Convicts Research Centre Inc., and E. Crawford. “Punishment and Discipline on Female Convict Ships to van Diemen’s Land,” 2020. https://femaleconvicts.org.au/convict-ships/convict-ship-punishments.

MHNSW-StAC. Musters and Other Papers Relating to Convict Ships, NRS 1155, Reel 2424, p.331. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

National Archives, Kew, England. Convicts Transported, HO11/4. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

National Archives; Kew, England. Surgeon’s Journal of Her Majesty’s Female Convict Ship Lord Sidmouth, Mr Robert Espie, Surgeon, from22 August 1822 to 1 March 1823, ADM 101/44/10, accessed via https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/docs/ships/LordSidmouth1823_SJ.pdf

Uebel, Lesley, and Hawkesbury on the Net. “Details for the Ship Lord Sidmouth (3) (1823).” Claim a Convict. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.hawkesbury.net.au/claimaconvict/shipDetails.php?shipId=256.

Introduction

Hannah Rigby had five known relationships with men throughout her life, although the identity of one of her partners has not yet been discovered.

Her partners were:

- Joseph Barrow, father of her first son (name unknown, born in Liverpool in 1815).

- Robert Crawford, father of her second son (Robert Frederick Rigby/Crawford, born in Parramatta in 1824).

- George Page, her husband from January 1825.

- An unknown man, father of her third son (Samuel Rigby, born in Sydney – or possibly Newcastle – in 1828).

- James Hexton, father of her fourth son (James Rigby/Hexton, born in Moreton Bay in 1832).

Partner 1: Joseph Barrow

On 26 January 1815, Hannah gave birth to a son in Liverpool. She sought financial assistance from the churchwardens and overseers of the poor of the parish of Liverpool, stating that she was a single woman and that the father of her child was Joseph Barrow, a comb-maker of Sutton near St Helen’s.[1]

Barrow’s family were partners in the very successful firm Barrow and Dagnall, which had been involved in the manufacture of ivory combs in Lancashire for over a hundred years.

In 1815, Hannah was somewhere between 15 and 20 years old; Barrow was about 46 and a newly married man.

In 1793 in Lancashire, Joseph Barrow had married Sarah Dagnall, no doubt a relation of his business partner. Sarah died, and in September 1813, Joseph married again. His second wife, also Sarah Dagnall (nee Thomas) was the widow of the comb-maker Henry Dagnall, with whom Barrow had conducted his business. Barrow had been a sponsor at the christening of the younger of Sarah and Henry’s two children and raised them as his own.

In February 1818 – three years after Hannah’s son was born – Barrow also fathered a child by Anne Tickle, another single woman.[2]

In March 18185 the churchwardens and overseers of the poor took Hannah’s case to the Liverpool Quarter Sessions. They ordered Barrow to pay the parish legal costs and expenses of the birth and maintenance up to that point, as well as two shillings sixpence weekly for as long as the child was under the care of the parish. The money would be passed on to Hannah for the support of her child.

Barrow died on 1 November 1842. The Liverpool Mercury reported the death of “Mr Joseph Barrow of the firm of Barrow and Dagnall, in his 74th year, very much respected.”[3]

Partner 2: Robert Crawford

Robert Crawford arrived in New South Wales on the Royal George in November 1821, about 15 months before Hannah’s arrival.[4]

Born on 3 February 1799, Crawford was 24 years old when he met Hannah (she was possibly 29). He was a Scotsman from Greenock, just west of Glasgow, a well-educated man from a middle-class family. He was the son of Hugh Crawford, a Glasgow “writer” (solicitor) and Jean Crawford, nee Bryce. Robert was the fifth child and third son in a large family. His mother died in 1812, when Robert was only 13. Robert and his siblings grew up on the family estate of Hillend, on a property of five or six acres.

Robert worked for the family business and was planning to become a “writer” like his father. One of Hugh Crawford’s clients was Sir Thomas Brisbane, the Scottish general of the British Army who would be governor of New South Wales from 1821 to 1825. For many years Hugh Crawford had been arranging significant loans to fund a wide range of Brisbane’s ventures. Sir Thomas Brisbane was well aware of all that he owed his solicitor. “I have ever considered myself more indebted to you than any man or indeed all men put together,” he wrote.

His gratitude might have been the reason for taking young Robert Crawford under his wing. In 1821, Sir Thomas Brisbane sailed to Sydney on the Royal George to take up his appointment as governor of New South Wales, replacing Governor Macquarie. Robert sailed with him, leaving the family business and giving up his plans to become a writer.

Crawford wrote many letters to his father that have been preserved by the Strathclyde Regional Archives and made available through the National Library of Australia. The letters suggest a vigorous and confident young man with a strong attachment to his family and a tendency to take his privilege for granted. Before the ship had even left the coast of England, he wrote as if he already had assurances of owning property in New South Wales.

Crawford arrived in Sydney on 7 November. At first, he was full of enthusiasm for his adopted land, “this beautiful Country”. The following month, Sir Thomas Brisbane appointed him assistant to the principal clerk in the colonial secretary’s office. He told Crawford confidentially that the former salary had been five shillings per day with rations, but he would double it for his protégé. Crawford accepted with pleasure and a remarkable display of entitlement.

He is uncommonly civil, and told me that this appointment was merely a stepping Stone, that the next best that became vacant he would give me; besides, he told me that if he was allowed a private Secretary he would appoint me to that Office. This is certainly very civil and no more than I deserve.

Crawford took over some care of Sir Thomas Brisbane’s affairs from his father. When he secured a loan for Sir Thomas, the governor thanked him by granting him 1000 acres of land. Of this land, 800 acres were at Prospect Common (the area between present-day Seven Hills and Prospect) and 200 at the Cow Pastures (south of the Nepean River floodplain, on the southern edge of the Cumberland Plain, home of the Dharawal People). Crawford was smug about his good fortune, while admitting that “A good many of the Settlers are annoyed at my having got it there.”

Crawford named the land at Prospect “Milton”, seeking favour of Sir Thomas Brisbane, who, he wrote, was the only representative of the Brisbanes of Milton and was very pleased with the name. Crawford named his land at Cow Pastures “Hillend” after his home in Scotland. He lived mostly in Sydney while the clearing of his land progressed through the labours of some 50 assigned convict servants.

In September 1822 he wrote that he had secured the lucrative job of principal clerk in the colonial secretary’s office. The incumbent in that office had been planning to retire to his farm within 18 months, but suggested that if his young assistant paid him £200, he would resign sooner, in Crawford’s favour. Crawford accepted the offer, paid the £200, and walked in to the job.

Hannah Rigby arrived in New South Wales in February 1823. Sometime during that year, her relationship with Robert Crawford must have begun. It seems likely that she was his assigned servant, but the incompleteness of the surviving assignment records make it impossible to verify this assumption.

Hannah gave birth to Robert Frederick Rigby on 6 June 1824 and named Robert Crawford as the father.[5] The child would have been born at the Parramatta Female Factory, which was the only “lying-in” place in the colony.

Sometime probably in 1824, Robert Crawford began an affair with Mary Campbell, the wife of Lewis Henry Campbell, formerly a sergeant of the Garrison Regiment in New South Wales, and superintendent of Crawford’s farm at Prospect. The relationship with Mary was a scandal. She left her husband and moved to Sydney to live with Crawford. The previous year, his strongest ally, Governor Brisbane, had been recalled to England; Brisbane’s replacement, Ralph Darling, was unimpressed with Crawford’s behaviour. Darling put pressure on Crawford to end the relationship, but Crawford refused. The governor then reduced his income. When Crawford appealed, the governor questioned his competence, describing him as “a person with so little pretension as a man of business”.[6]

Furious, Crawford resigned. He wrote to his father: “I can only repeat that I have been shamefully used”. When Crawford sought compensation for the loss of his position, Darling wrote that he considered the young man unqualified and displaying a “disregard to Morality”, that made him unsuited to the office.[7]

Crawford fell back on Hillend for his income and in February 1828 was forced to sell Clyde Bank, the grand home he had recently built in Sydney. He moved to Prospect with Mary. Though they never married, the pair had four children together: Mary, Robert, George Canning and Agnes. The eldest, Mary, was born in May 1826, only two years after the birth of Crawford’s son by Hannah Rigby.

Crawford persuaded his beloved brother Thomas (whom he nicknamed “The Corporal”) to join him in New South Wales in 1825, and Thomas had helped him in his farming ventures. The brothers were successful and well respected in the district.

In 1825, Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane had granted land in the Hunter Valley to Robert and Thomas. Their ownership of those titles was later disputed by the Darling government, leading to legal wrangles that lasted for years. In May 1847, Robert Crawford returned to Scotland to seek Sir Thomas Brisbane’s help in resolving the problem. Brisbane supported Crawford’s claim, and the land grants were finally confirmed. But on 12 November 1848, before he could return to Australia, Crawford fell from the banisters of a hotel, split his skull, and died. It was believed that a heart attack had caused the fall.

Partner 3: George Page

Hannah Rigby’s third known partner was ticket-of-leave man George Page. She married him on 3 January 1825, at St John’s Church of England, Parramatta, with Rev Marsden officiating.[8] The marriage was probably a result of the notorious “marriage market” system at the Parramatta Female Factory.

George Page was born in Braughing, Hertford, and baptised on 20 May 1798. His certificates of freedom describe him as 5’ 8 ¼” tall, with a ruddy complexion, black hair and dark eyes.[9]

Page had been transported as a convict for stealing. In the middle of the night on 9 February 1817, near Tottenham, in the company of two others, Page had stolen goods from a wagon. He was known to the wagon driver, Jeremiah Aves, who was travelling from Norwich to London. The three thieves got away in the night, but at 3.15 am William Green, a watchman, came upon two men carrying a chest of tea. One of them was named Bell, and the other was George Page. When Green questioned them, they said they were guards to the wagon, that somebody else had stolen the tea, and that they were taking it back. Suspicious, he followed them. Page ran away with his takings, but Green caught Bell and locked him and the tea up. With another watchman, Green then followed Page, found him behind a haystack and put him in a cage. By daylight he had escaped. In the meantime Page had told a labourer where the stolen goods could be found, and they were recovered.

George Page was eventually recaptured and tried at Middlesex for grand larceny on 21 April 1819. He was indicted for stealing, on the 9th of February, 1817, one chest, value 1 s.; 60 lbs. of tea, value 20 l. [sic]; one box, value 1 s.; 100 lemons, value 10 s.; one peck of nuts, value 6 s., and one peck of chestnuts, value 5 s., the goods of William Mack and John Mack. He was found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ transportation to New South Wales.[10]

Page was held at Newgate before being transferred to the prison hulk Justitia at Woolwich. He sailed to New South Wales on the Shipley, arriving in 1820.[11]

By 1821 Page was the assigned servant of John Nicholson, who took on the position of harbour master in February 1821.[12]

George Page’s ticket of leave was granted on 18 November 1824.[13] He applied to marry Hannah Rigby on 7 December[14], and the pair wed on 3 January 1825.[15]

Page’s certificate of freedom was issued on 4 May 1826.[16] By the following month, he was back in custody facing a charge of larceny. He was accused of stealing fabric from the ship Lord Rodney, which had been at anchor in the harbour. Fabric had gone missing from the ship back in December 1825. Some time later, a woman was seen on the streets of Sydney wearing a dress made up from fabric of the same distinctive pattern. When questioned, she said she had bought it from George Page. Police searched his house and found more of the fabric: some made up into curtains, and some into dresses or cut up ready to make dresses. In explaining how he had come by the fabric, Page told two different stories: first that he had bought it at the marketplace, and then that it had been brought to his house for sale by “a black man”.[17]

Page was taken into gaol on 26 May and tried on 10 June. He was found guilty of possession of stolen property and sentenced to seven years’ transportation to Moreton Bay.[18]

Before he was sent to Moreton Bay, Page was held in the hulk the Phoenix for a couple of months.[19] Then he was transferred to the Amity,[20] and arrived at the Moreton Bay establishment on 22 September 1826.[21]

When Hannah arrived at Moreton Bay in November 1830, her husband George Page was still serving his time there. There is no evidence, however, that they rekindled their relationship.

Page’s certificate of freedom was issued on 23 April 1833, and he was returned to Sydney.[22]

![George Page’s certificate of freedom, issued 30 March 1833.MHNSW - StAC: NRS-12210 [4/4315] 33/0251.](https://harrygentle.griffith.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/rsz_nrs_12210_butts_of_certificates_of_freedom_george_page_1833-272x300.jpg)

MHNSW – StAC: NRS-12210 [4/4315] 33/0251.

Partner 5: James Hexton

Hannah Rigby’s fifth (but fourth known) partner was the seaman James Hexton. They met at Moreton Bay, when Hannah was serving her first colonial sentence and Hexton was working with the boat crew. Much of what has been previously believed about Hexton was taken from the reminiscences of his son (also James Hexton), published in the Queenslander in 1909.[23] He wrote that his father was from Waterford, Ireland, and that he had been a lieutenant in the British Royal Navy and had fought and been wounded at the Battle of Trafalgar under Nelson. The article contains many errors, however, and cannot be relied upon. No record has yet been found to verify Hexton’s career in the Royal Navy, but he almost certainly did not hold as high a rank as lieutenant.

The first evidence of James Hexton’s arrival in New South Wales is dated from 1823. He was on the crew of the British merchant navy ship Zenobia,[24] under the command of Lieutenant John Lihou, sailing from Manila. Zenobia called in to Sydney, but before it departed in April 1823, Hexton absconded and joined the crew of Woodlark instead.[25] In May he left Sydney temporarily for Batavia on the Woodlark,[26] and later that year he was heading to “The South Sea Fishery” on the same vessel.[27]

In 1831, Hexton travelled from Sydney to Moreton Bay to take on the role of master of the Regent Bird, a cutter used to transport supplies and convicts to and from the settlement. However, when he arrived, it turned out that Edward King had already been appointed to the role. Hexton stayed on in the position of seaman in charge of the cutter Glory on a lower rate of pay.

On 27 September 1832, Hexton’s son by Hannah Rigby, James Rigby, was born. Although his father was not identified in the birth register, both parents were named on James’s death certificate.[28] The Queenslander article of 1909 makes it clear that Hannah’s son knew who his father was and by then had taken his surname.

James Hexton (senior) lived with the crew at the pilot station at Amity Point (or Pulan) on Stradbroke Island (Minjerribah) for many years. He was finally appointed to the position of boat pilot in 1834, after the death of the pilot William Morris.[29] Hexton and his crew (some of the more trusted convicts) mingled with the Quandamooka people who were the original inhabitants of the island and whose knowledge of the seas and the wildlife they relied upon. Some of the Indigenous men were members of the boat crew, and many of the European crew members had relationships with the Indigenous women.

Hexton’s own relationship with the Quandamooka people is complicated. Seven years after his son James was born, he fathered another son with “An Aboriginal Woman” of Amity, born on 4 May 1839. He took the child away to be raised by his friend, Andrew Petrie, with Petrie’s own family in Brisbane. Hexton had the child baptised “Edward Petrie Hexton” (known as “Neddy”) and made the Petries godparents. He paid maintenance and visited Neddy whenever he was in Brisbane, and he even bought two blocks of land in Queen Street to be held in trust for his son when he came of age.[30] Neddy’s mother’s feelings about the arrangement have not been recorded. Sadly, Neddy died from “consumption” (tuberculosis) at the age of only 19. He had been living in Queen Street and working as a carpenter for John Petrie.[31]

By the late 1840s, the South Passage, which had been the usual shipping route into Moreton Bay, had become shallower and more dangerous. Several shipping accidents had occurred. After the disastrous wreck of the Sovereign in 1847, the decision was made to use the North Passage instead, and thus a new pilot station was built on Moreton Island. Hexton and his crew moved to the new residence in 1848.

Captain Clunie, commandant of the penal establishment, described James Hexton as “a steady intelligent man, a good seaman”.[32] It seems that Hexton was well liked and respected in Brisbane, although neglectful of his business affairs and a heavy drinker.[33]

Whether Hexton ever had a “real” or ongoing relationship with Hannah Rigby, as his son implied he did in the feature article, is unknown. Given that Hexton lived on the islands and Hannah in Brisbane, and given Hexton’s relationship with the “Aboriginal Woman” and the birth of Neddy, it seems unlikely.

On 15 April 1851, Hexton and five crewmen were caught up in a squall on their return from guiding the barque Cape Horn out to sea. He tried to bring his boat his to shore at Comboyuro Point on the north-west of Moreton Island, but he dropped his steer oar and the vessel capsized. Three of the crew made it to shore, while two clung to the upturned boat and Hexton floundered. He was wearing a heavy coat and could not swim. About 100 yards from the shore, he disappeared beneath the waves. With the help of some Quandamooka men, the two crewmen clinging to the boat were rescued, but James Hexton’s body was never found.[34]

[1] Lancashire Archives, England. Liverpool. Order of Filiation and Maintenance of Bastard Son of Joseph Barrow of Sutton, Comb-maker, and Hannah Rigby, Singlewoman, QSP/2680/89, 8 Mar 1815. Accessed via Ancestry.com; also Lancashire Archives, England. Lancashire Courts of Quarter Sessions – 1583-1999, Order Book, QSO/2/184, p.260. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[2] Lancashire Archives, England. Windle. Order of Filiation and Maintenance of Ann, Bastard Child of Joseph Barrow of Hardshaw, Comb-maker, and Ann Tickle, singlewoman, QSP/2735/75, 1818.

[3] Liverpool Mercury, November 4, 1842, p.7.

[4] Unless otherwise stated, biographical details about Robert Crawford are taken from his letters, which have been transcribed and annotated in Robert Crawford and Thomas Crawford, Young & Free: Letters of Robert and Thomas Crawford 1821-1830, ed. Richard Crawford (Macquarie, ACT: R. Crawford, 1995). The handwritten letters have been digitised and can be found at NLA in the Ardgowan Estate Records, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1127486562.

[5] “Robert Rigby” Baptism of Robert Frederick Rigby, Baptisms, 1790-1825, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, 12 Dec 1824, Ref. no. REG/COMP/1, Vol 01. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[6] Committee Australia Parliament Library, Historical Records of Australia: Series 1, vol. XII (1919; Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament), accessed August 27, 2023, p.552, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-476838109.

[7] Committee Australia Parliament Library, Historical Records of Australia: Series 1, vol. XIII (Sydney: Library Committee of The Commonwealth Parliament, 1920), p.43, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-477011992.

[8] “George Page and Hannah Rigby” 1825, Marriage certificate of George Page and Hannah Rigby, 3 Jan 1825, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg. no. 3471/1825 V18253471 3B.

[9] MHNSW-StAC. Register of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 12208, [4/4424, Reel 602], Entry No.20/5280, and MHNSW-StAC. Butts of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 12210, [4/4315, Reel 990], Entry no. 33/0251. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[10] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) April 1819. Trial of George Page (t18190421-139). Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18190421-139 (Accessed: 19th June 2024).

[11] MHNSW-StAC. Musters and Other Papers Relating to Convict Ships. NRS 1155, Reel 2427, [2/8277], Also MHNSW-StAC. Indents, NRS 12188, [4/4007], fiche 645. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[12] MHNSW-StAC. Page George, Index to the Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825, [4/5781], p.59, Reel 6016, Date 08/09/1821.

[13] MHNSW-StAC. Registers of Tickets of Leave, NRS 12200; Item [4/4060], Reel 890, Entry no.24/518. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[14] MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Index to the Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825, Reel 6014, [4/3513]. Accessed online at https://search.records.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX2482177

[15] “George Page and Hannah Rigby” 1825, Marriage certificate of George Page and Hannah Rigby, 3 Jan 1825, certified copy, NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Reg. no. 3471/1825 V18253471 3B

[16] MHNSW-StAC. Register of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 12208; [4/4424], Reel 602, No.20/5280. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[17] “Supreme Criminal Court.,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 21, 1826, p.3. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2186010.

[18] MHNSW-StAC. George Page, Criminal Court Records Index 1788-1833, 13477 [T23] 26/89, 10/06/1826.

[19] MHNSW-StAC. Discharge Books [Phoenix], 1825-1830, NRS 2428, Reel 822, 4/6285. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[20] Australian, September 26, 1826, p. 2. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/37071777/4248905.

[21] SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.1, letter [4/1917.1], pp.320-324. George Page arrives at Moreton Bay on the Amity on 22 Sept 1826.

[22] MHNSW-StAC. Butts of Certificates of Freedom, NRS 12210, [4/4315, Reel 990], Entry no. 33/0251. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[23] “The Oldest Living White Native,” Queenslander, August 7, 1909, p.22, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/21829655.

[24] MHNSW-StAC. Ships Musters. Vols. 4/4771–75, NRS 1289, Item 4/4774, Reel 562, p.148. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[25] MHNSW-StAC. Ships Musters, NRS 1289, Item 4/4774, Reel 562, p.245. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[26] “Classified Advertising,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, May 8, 1823, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2181846.

[27] MHNSW-StAC. Ships Musters, NRS 1289, Item 4/4774, Reel 562, p.406. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[28] Death Certificate Image, James Hexton, Registration no. 1914/B/18964, QLD Govt Family History Research Service.

[29] SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.10, letter [38/4504], pp.43-44.

[30] MHNSW-StAC. James Hexton Intestate Estates Index 1821-1913, [6/3521] file no. 1101.

[31] “Edward Petrie Hexton” 1858, Death Certificate of Edward Petrie Hexton, 9 Sept 1858, Death image, QLD Government Family History Research Service, 1858/B/260.

[32] SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.8, letter [35/264], p.626.

[33] MHNSW-StAC. James Hexton Intestate Estates Index 1821-1913, [6/3521] file no. 1101.

[34] Details of James Hexton’s death were reported in “Melancholy Accident,” Melbourne Daily News, April 30, 1851, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226519565, and SLQ. Colonial Secretary’s Papers. Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822 – 1860. Reel A2.22, letter [51/4382], pp.189-193.

Hannah Rigby gave birth to three sons in Australia. Another son, born in Liverpool before her transportation to Australia, has recently been discovered.

Convict women held in female factories were normally only allowed to keep their children with them up to the age of three years. After that, their children could be placed in an orphanage. Convict women who were assigned as servants also faced losing their children, as employees might refuse to let children to accompany them. It seems Hannah did her best to keep her Australian-born sons with her for as long as possible and was more successful in this regard than some women in her position.

Child 1: (1815–)

Accessed via Ancestry.com.

Hannah Rigby’s first child was born in Liverpool on 26 January 1815. Hannah, as a young, single seamstress in need of support, approached the churchwardens and overseers of the poor of the parish of Liverpool for financial assistance in March 1815. She named her son’s father as the 46-year-old, wealthy, married comb-maker Joseph Barrow. At the Liverpool Quarter Sessions, Barrow was ordered to pay for the child’s maintenance.[1]

Since she named later sons after their fathers, it would be reasonable to guess that Hannah called this child Joseph. However, since the name was not given in the filiation order, this remains speculation that cannot be confirmed. Without a name, tracing the child’s fate conclusively is impossible. Since the death rate for “illegitimate” children in the early 19th-century was much higher than the rate for children with married parents, Hannah’s son might not have lived long. The burial of a baby named Joseph Rigby was registered in Westleigh (not far from Barrow’s hometown) in April 1815, only a month after the filiation order was made. Lack of details in the register prevent us from knowing whether this was Hannah’s son.

Child 2: Robert Frederick Rigby/Crawford (1824–1852?)

Hannah’s son Robert was born at Parramatta on 6 June 1824.

![Robert at Moreton Bay School, 1831. MHNSW-StAC: Cash Vouchers [Clergy and School Lands Corporation], NRS 803, [4/310], Parochial Schools Vol. III.](https://harrygentle.griffith.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/rsz_robert_at_mb_school_1831-272x300.jpg)

After George Page’s 1826 arrest and transportation to Moreton Bay, young Robert remained with his mother, who was still under sentence. He was with her when she absconded from service for two weeks in Sydney in 1826, and he was with her in Newcastle in November 1828 when the census was recorded. He was also with her on the government cutter that took her to Sydney in March 1830 following her arrest for theft,[4] and when she was transported to Moreton Bay in October that year.

From 1831, Robert attended the Moreton Bay School, where the children of convicts and the military were educated together.[5]

He must have returned to Sydney with Hannah when she was sent back in February 1837 at the expiration of her seven-year sentence.

When Hannah re-offended later that year and was transported again to Moreton Bay, Robert would have been about 13 years old. He would not have accompanied her to Moreton Bay; being old enough to work, he was probably apprenticed out or sent to a household to work as a servant in Sydney. No records have yet been found to show his movements at that time.

In 1845, Robert applied to marry Mary Kay,[6] a ticket-of-leave convict from Manchester with a long string of convictions who had been sentenced to 14 years for stealing money. Robert and Mary were married at the Scots Church in Sydney on 2 September by John Dunmore Lang. Robert was 21 years old, and Mary either 23 (according to her marriage certificate) or, more likely, 29 (according to the transportation documents and her application to marry). Robert’s name was recorded in both the application to marry and the marriage register as “Robert Crawford, or Rigby”.[7]

A Robert Rigby was called to give his eyewitness account of an assault at the wharf in Brisbane in 1848; this might have been Hannah’s son.[8]

A cabinet maker named Robert Rigby who died in Sydney in November 1852[9] was probably Hannah’s son. The fate of his wife is unknown.

Child 3: Samuel Rigby (1828–1853)

Hannah’s third son, Samuel Rigby, was three months old at the time of the 1828 census. Since the census was conducted in November of that year, Samuel must have been born in about July or August 1828.

Like his brother Robert, Samuel was with Hannah on the government cutter that took her to Sydney in March 1830 following her arrest for theft in Newcastle. Hannah had Samuel baptised in Sydney at St Philips on 30 May 1830. She gave his father’s identity as “Samuel Rigby, clerk” and his age as almost 17 months, which was five or six months younger than his actual age.[10]

Samuel was also with Hannah when she was transported to Moreton Bay in October 1830.

He was treated for intermittent fever at the convict hospital in Moreton Bay in February 1831.[11]

Like Robert, Samuel must have returned to Sydney with Hannah when she was sent back in February 1837, at the expiration of her seven-year sentence. When she re-offended later that year, Samuel would have been about nine years old. It seems he did not accompany her back to Moreton Bay. His name does not appear in any orphanage records or other correspondence; like his brother Robert, he was probably apprenticed out or sent to a household to work as a servant in Sydney.

In 1846, Hannah put the following notice in the Sydney Morning Herald:

SAMUEL RIGBY, about 18 years of age, a native of the colony, supposed to be in the interior, is earnestly requested communicate to with his parent, to the following address; and any person knowing his present address, would confer a great favour by sending the same to HANNAH RIGBY, 119, Elizabeth-street. Sydney.[12]

An unclaimed letter addressed to him at Berrima in April 1847 suggests that Hannah might have suspected her son was in Berrima.[13]

Mr Samuel Rigby was on a passenger list of the Tamar, sailing from Sydney to Moreton Bay, which departed 10 August 1847.[14] It arrived on 15 August.[15]

Samuel Rigby died in Brisbane on 7 February 1853.[16]

Child 4: James Rigby/Hexton (1832–1914)

On 27 September 1832, Hannah Rigby gave birth to her fourth son, James Rigby, who was later known by his father’s surname, Hexton. In the register of births, his mother is registered as unmarried, and his father is not named.[17] His father has since been identified as the boat pilot, James Hexton.

It seems that Hannah might have left James behind in Moreton Bay – willingly or unwillingly – when she was sent back to Sydney at the expiration of her sentence in 1837. Young James had memories of being at Amity (Stradbroke Island) and it is possible that he spent some time with his father at the pilot station there. But when his mother, having returned to Moreton Bay for her second colonial sentence, was assigned to Dr David Keith Ballow, her youngest son went with her.

In 1909 a feature article about James “Jemmy” Hexton appeared in the Queenslander.[18] It summarises his life as the “oldest living white native” of Queensland and, although many details in it are demonstrably false, it provides us with a glimpse of his story, as does his 1914 obituary.[19]

According to Hexton’s account, as a young man he worked first in the Customs Department and later the Harbors Department. He then left town briefly for a stint of shearing at Mondure and Barambah stations, then travelled up to the Dawson in the north. He had a period of mining at the Rocky Diggings at Armidale, NSW, before returning to Brisbane.[20]

He was still a young man when he started working for William Pettigrew’s sawmill in Brisbane, probably procuring timber for the mill. (Pettigrew had established Brisbane’s first steam sawmill by the river in William Street in 1853.) He also worked for the company Peto, Brassey, and Betts, building bridges. The projects that Jimmy worked on included the first bridge over the river, the temporary Brisbane Bridge, which was built in 1865 and collapsed less than two years later; the first Victoria Bridge, built in 1874; and the Indooroopilly Bridge.

Although a marriage certificate has not yet been found, according to his children’s birth certificates, James Hexton married Irish-born Ellen Casey on 5 June 1854. The couple had nine children, eight of whom reached adulthood. Ellen died on 25 July 1875.

Their children were:

1. William Joseph (1855–1924)

Married Eva Kathleen Harvey 7/10/1891.

Three children:

William Edwin Hexton (1892-1892)

- Died in infancy 23/10/1892 – Registration: 1892/B/25452.

James Harold Hexton (1894-1945)

- Born 28/1/1894 – Registration: 1894/B/53958.

- Married Nellie Elizabeth Feely in 1942. Registration: 1942/B/50324.

- Died 25/2/1945. Registration: 1945/B/811. Death certificate states: Died of cerebral haemorrhage, hypertension at Brisbane Hospital. Labourer. Buried at Toowong 26 Feb. Married at age 48 to Eleanor (Nellie) Elizabeth Feely, no issue.

Ellen Mary Hexton (?–1907)

- Died 23/4/1907 (Registration: 1907/B/7977). Died in childhood, no issue.

- Death notice: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/175568338 & https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/183104367.

2. James (1858–1882)

- Born 29 June 1858.

- Broke off with a woman Mary Jones, who drowned herself in the river Nov 1876 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/174706422.

- Imprisoned for 3 months at St Helena (27 August to 1 November 1877) for using obscene language.[21]

- Died 5 November 1882 from “Congestion of the brain”. Death certificate states that he was a labourer, unmarried, lived at Margaret St, had been sick 24 hours. Magisterial inquiry held by EDR Ross JP on 7 Nov 1882.

- The enquiry into death of James “Exton” found he died of congestion of the brain due to excessive drinking https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3409512.

3. Robert (1857 or 1858–)

- Was employed in the Government Printing Office in 1878 and by “Gaujard and Elson” in 1879 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/19779495, see also https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/19779710.

- Was fined for being illegally on enclosed premises in 1879 (https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/897708.

- Was fined in Brisbane for drunkenness. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/183371520.

- Might have been living at 1 High St Kogarah NSW in 1930.[22]

4. Hannah (1860 or 1861–1949)

- Married William Samuel Binder 19/7/1884 – Registration: 1884/B/9014.

- Lived in Victoria and had a large family. Probably has living descendants.

5. Elizabeth (1862 or 1863–1891)

- Married Edwin Allen in QLD 1/3/1888 – Registration: 1888/B/12168.

- Died 4/4/1891 – Registration: 1891/B/24037.

- Elizabeth died of heart disease (valvular), was sick 3 weeks, lived at Merton Road Woolloongabba, no children. Buried South Brisbane, Baptist.

6. Mary Ann (1866–1964)

- Born 22 March 1866.

- Married Charles Shaw in Brisbane (at age 21 according to death cert, but she was actually 22)

- Had a son Charles James.

- Charles Shaw died, and Mary Ann married Charles Godwin in Caboolture when she was aged 34. They had three children together, but the youngest (a son) died in childhood. Their children who reached adulthood were:

- Everlien Ellen, born 1901 or 1902.

- George Charles, born 1902 or 1903.

- Her children produced descendants who are living today.

- Mary Ann died of bronchopneumonia 18 July 1964, age 98, in Nambour Hospital.

7. Thomas (1868–1932)

- Born 30 January 1868.

- Thomas was unmarried and lived in Caloundra.

- Died 27 February 1932. Registration: 1932/B/16660. Death certificate shows he died at Brisbane Hospital, age 64 of carcinoma of prostate, uraemia, coma? Certified by his sister Mary Ann Godwin of Caloundra. Buried at South Brisbane 29 Feb 1932.

- A death notice states: “Mr. Thomas Hexlon, a Caloundra resident for many years, died in the Brisbane General Hospital on February 27 last at the age of 62 years. Deceased was a native of Brisbane. The deceased, who was unmarried, is survived by two sisters, Mesdames M. A. Godwin (Caloundra) and W. Binder (Melbourne).”[23]

8. Ellen (1869–1900)

- Married Richard James Street on 22 August 1894. Registration: 1894/B/16978.

- No children.

- Died 27 March 1900.

- “Nellie” was buried at Toowong Cemetery.[24]

9. Jane (1872–1875)

- Born 20 June 1872.

- Her birth certificate calls her Jane, but her mother’s death certificate calls her Eva Jane.

- Died 15 April 1875.

- A magisterial inquiry, held on 19 April, found that she died from congestion of brain and lungs caused by brandy.[25]

[1] Lancashire Archives, England. Liverpool. Order of filiation and maintenance of bastard son of Joseph Barrow of Sutton, comb-maker, and Hannah Rigby, singlewoman, QSP/2680/89, 8 Mar 1815. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[2] “Robert Rigby” Baptism of Robert Frederick Rigby, Baptisms, 1790-1825, St. John’s Anglican Church Parramatta, 12 Dec 1824, Ref. no. REG/COMP/1, Vol 01. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[3] “Robert Crawford”, Baptism of Robert Crawford, Certified copy, NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Reg no. 824/1824 V1824824 8.

[4] MHNSW-StAC. Rigby, Hannah. Index to Colonial Secretary Letters Received [4/2070], Letter no.

30/2382.

[5] Enrolment details at the Moreton Bay school have been gleaned from JOL, SLQ. E.R. Wyeth, Education in Queensland, OM75-30, Part 1, Appendix 11 and MHNSW-StAC: Cash Vouchers [Clergy and School Lands Corporation], NRS 803, [4/310], Parochial Schools Vol.III; and MHNSW-StAC: Cash Vouchers [Clergy and School Lands Corporation], NRS 803, [4/318], Parochial Schools Vol.II.

[6] MHNSW-StAC. Convicts Applications to Marry 1825-1851, Crawford, Robert; alias Rigley, Robert, Kay, Mary, NRS 12212 [4/4514 p.101], COD 15, Reel 715, Fiche 800-802. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

[7] “Robert Crawford and Mary Kay” 1845, Marriage Certificate of Robert Crawford and Mary Kay, 2 Sept 1845, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, No.533, Vol.77.

[8] “Domestic Intelligence,” Moreton Bay Courier, September 30, 1848, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3710059.

[9] “Robert Rigby” 1853, Death Certificate of Robert Rigby, 8 Nov 1852, Certified copy, NSW Registry of BDM, Reg. no. 599/1852 V1852599 110.

[10] “Samuel Rigby”, Baptism of Samuel Rigby, Certified copy, NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Reg no. 186/1830 V1830186 14.

[11] QSA. Register of cases and treatment – Moreton Bay Hospital, 1830–1831, ITM2895 (part 1) and ITM2858 (part 3).

[12] SMH, January 15, 1846, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/12884692.

[13] “Unclaimed Letters,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 10, 1847, p.3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/12893400/1516863.

[14] “Departures,” Sydney Chronicle, August 11, 1847, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/31752917.

[15] “Shipping Intelligence,” Moreton Bay Courier, August 21, 1847, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3713780.

[16] “Samuel Rigby” 1853, Death Certificate of Samuel Rigby, 7 Feb 1853, Certified copy, NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Reg. no. 1797/1853 V18531797 39B.

[17] QSA. Book of half-yearly returns of baptisms at the Moreton Bay penal settlement 1832-1835, ITM869685.

[18] “The Oldest Living White Native,” Queenslander, August 7, 1909, p.22, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/21829655.

[19] “Passing of a Pioneer,” Truth, February 22, 1914, p.4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202668845 and “The Oldest White Native,” Brisbane Courier, February 18, 1914, p.5, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/19949902.

[20] “Passing of a Pioneer,” Truth, February 22, 1914, p.4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202668845.

[21] QSA. Register of male prisoners admitted – H. M. Penal Establishment/Gaol, St Helena, ITM92280, digital file part 1, digital file DR56516, prisoner no.1141.

[22] Sands Directories: Sydney and New South Wales, Australia, 1861–1933. Balgowlah, Australia: W. & F. Pascoe Pty, Ltd.

[23] Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser March 4, 1932, p.7, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/76884490

[24] The Telegraph March 28, 1900, p.1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/173776254

[25] The Queenslander, April 24, 1875, p.2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/18335753