This project explores the key aspects of town life and policing of today’s Brisbane in its transition years

Policing a Colonial Metropolis: from Moreton Bay to Brisbane

Exploring Policing of Pre-Separation Brisbane.

In 1859, Queensland gained political freedom by separating from New South Wales, but it inherited a policing system badly in need of reform. At this time, the settled area of the colony was divided into 17 districts, each with its own police force under a Chief Constable, who took orders from the local magistrate. As the population grew and the colonial landscape diversified so did the policing network; the Mounted Border Police, the Native Police and the Volunteer Force (cavalry and infantry) all co-existed with the town forces.

The project explores the aspects of early colonial town policing experiences. Simultaneously, by re-creating life and service stories of the early policemen, the project seeks to explore the key issues impacting these men’s service such as community integration and moral policing; property crime; violent crime and patrol duties; the treatment of indigenous communities; and sweeping administrative reforms in response to jurisdictional and administrative changes. By offering a manifold approach to narrating the history of policing in the early colonial metropolis, the project contributes much-needed nuance and complexity to our understanding of crime and policing of a fledging early colonial town and the experiences ‘on the job’ of very first men in blue.

About the project

This project has been developed from the research findings of Dr Anastasia Dukova in conjunction with Queensland Police Museum. Dr Dukova is currently an Adjunct Research Fellow with Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research and a Visiting Fellow at Griffith’s Harry Gentle Resource Centre, which is a digital portal of resources concerning the pre-Separation (pre-1859) history of Queensland. Anastasia is a policing historian specialising in the history of urban policing, with a primary focus on Ireland, nineteenth-century Australia and North America. She is particularly interested in the impact of Irish policing experience on the development of the colonial policing models. Anastasia is the historian behind an award-winning project Digital Colonial Brisbane. Her recent monographs are A History of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Its Colonial Legacy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) and Policing Colonial Brisbane (UQP, 2018). The current project aims to consolidate historical information regarding the key aspects of town life and policing of Brisbane in its transition years, from the halting of the transportation of convicts into the settlement in 1839, to establishment of Brisbane as a colonial capital in 1859. Utilising an array of primary records, the project investigates the challenges the nascent colonial town policemen, also known as foot policemen, faced. What was their day, or night, ‘on the job’ like? Who were these men?

JOHN MCINTOSH (1828-1833, resigned) AND THE CONVICT POLICE

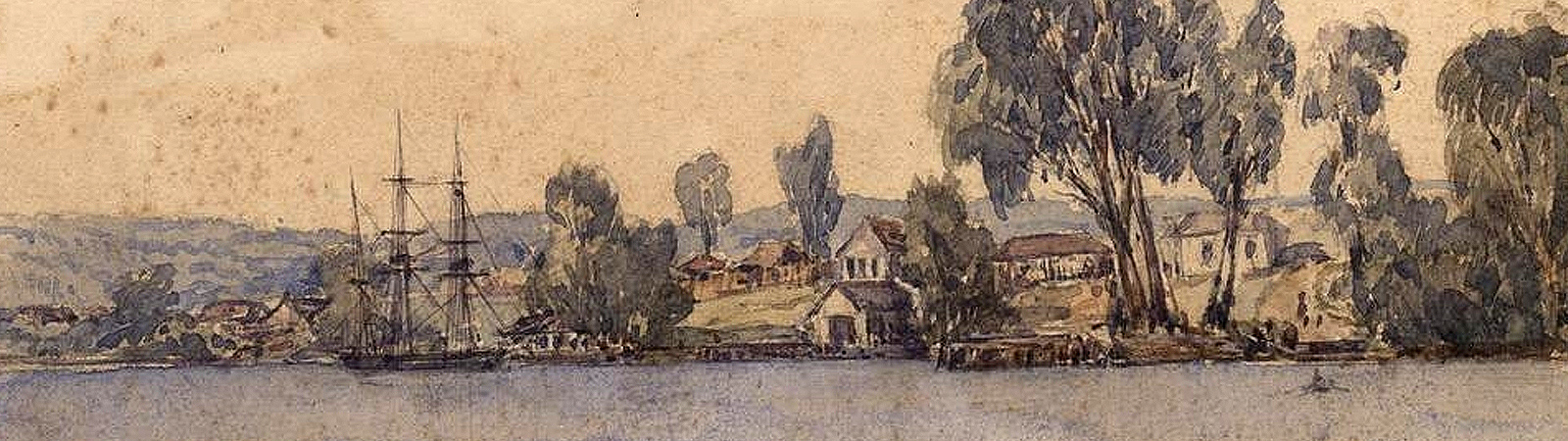

(Map of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay 1839 [cartographic material] G. W. Barney, SLNSW; Town of Brisbane by Henry Wade, 1843, QSA Item ID 714293)

The Moreton Bay Penal Settlement

John McIntosh, a lifer from Scotland, was the first Chief Constable (1828- 1833) of the Moreton Bay police force consisting entirely of convicts.

The centralised Queensland Police Force was formally organised when the Police Act 1863 (27 Vic No 11) came into force. The foundation for the future organisation was laid in 1838, by the first Police Act (2 Vic No 2). Prior to that, enforcement of law and order was the duty of the Military Commandants of the Moreton Bay penal settlement. This was set up in Brisbane Town in 1824.

The iconic ballad, the Moreton Bay, evokes a bleak image of the settlement. The words evoke the terrible fate prisoners suffered there, ‘One Sunday morning as I went walking/ By Brisbane Waters I chanced to stray/ I heard a prisoner his fate bewailing/ As on the sunny river banks he lay.’ Their isolation, ‘I am a native of Erin’s Island/ And banished now from my native shore,/ They tore me from my aged parents/ And from the maiden whom I do adore.’ The ballad compares conditions of sentences served at Port Macquarie, Norfolk Island and Emu Plains, Castle Hill and ‘cursed Toongabbie’; ‘At all those settlements I’ve worked in chains/ But of all places of condemnation/ And penal stations of New South Wales/ To Moreton Bay I have found no equal/ Excessive tyranny each day prevails.’ Captain Patrick Logan, who arrived in 1826, was reputedly a harsh disciplinarian, despised by the convicts he controlled:

For three long years I was beastly treated,

And heavy irons on my legs I wore;

My back with flogging is lacerated

And often painted with my crimson gore.

And many a man from downright starvation

Lies mouldering now underneath the clay,

And Captain Logan he had us mangled

At the triangles of Moreton Bay

(Bob Reece, Exiles from Erin: Convict Lives in Ireland and Australia. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), pp. 171-2)

Between 1826 and 1829 the number of prisoners at Moreton Bay rose from 200 to nearly 1000. In 1836, the writer, James Backhouse, a benevolent Quaker, accompanied by his friend George Washington Walker, visited Brisbane and described the town as consisting of ‘the houses of the Commandant and other officers, the barracks for the military, and those for the male prisoners, a treadmill, stores, etc’. (William Coote, History of Colony of Queensland from 1770 to the year 1881, Vol 1. Brisbane, 1882, pp. 24) They found the settlement ‘prettily situated on the north bank of the River Brisbane’ navigable fifty miles further up for small sloops, with ‘some fine cleared and cultivated land on the south side bank opposite the town.’ (ibid) Adjacent to the Government House, the visitors noted ‘the Commandant’s garden, and twenty-two acres of Government gardens for the growth of sweet potatoes, cabbages, and other vegetables for the prisoners. Bananas, grapes, guavas, pineapples, citrons, lemons, shaddocks.’ (ibid) The climate being nearly tropical, sugar canes were grown for fencing, there were a few thriving coffee plants, ‘but not old enough to bear fruit’. Backhouse predicted that coffee and sugar would probably at some time be cultivated as crops.

The convicts, they observed, worked the treadmill:

The treadmill is generally worked by twenty-five prisoners at a time, but when it is used as a special punishment, sixteen are kept upon it fourteen hours, with only the interval of release afforded by four being off at a time in succession. They feel this extremely irksome at first, but, notwithstanding the warmth of the climate, they become so far accustomed to the labour by long practice as to bear the treadmill with comparatively little disgust, after working upon it for a considerable number of days. Many of the prisoners were occupied in landing cargoes of maize or Indian corn from a field down the river, and others in divesting it of the husks. To our regret, we heard an officer swearing at the men, and using other improper and exasperating language. The practices forbidden by the Commandant; but it is not uncommon, and, in its affects, is, perhaps, equally hardening to those who are guilty of it, and those who are under them… We visited the prisoners’ barracks a large stone building, calculated to accommodate 1,000 men, but now occupied by 311. We also visited the penitentiary for female prisoners, seventy-one of whom are here. Most of them, as well as of the men, have been re-transported for crimes that have been nurtured by strong drink. The women were employed in washing, needlework, picking oakum, and nursing. A few of them were very young.

(William Coote, History of Colony of Queensland from 1770 to the year 1881, Vol 1. Brisbane, 1882, pp. 24-5)

In its first five years the Brisbane penal settler population increased by more than twenty-fold, from approximately 50 in 1824, the year of establishment of the Moreton Bay penal colony, to 1108 in 1829, including 18 female convicts, the very first convict women to arrive into the settlement. Their number had increased to 71 by 1836. The arrival of female convicts flamed much local enthusiasm at the time. According to Pugh’s Almanac, ‘the “female factory” proved a grand source of intrigue and vice, and some queer tales [were] handed down to us – the gay Lotharios of which were not by any means the lowest people in the settlement.’ (Pugh’s Almanac 1859, p. 65) Although a wall was constructed around the building, which was quickly found to be necessary, it did ‘not seem to have been proof against the agility and nimbleness of the midnight rovers who had first all secured the blindness of the warders by a liberal use of bucksheesh.’ (Ibid) Regardless of the counter measures, intrigue and licentiousness were soon rife.

Throughout the 1830s, increasing agitation to bring about the end of the system of convict transportation led to a decline in prisoners arriving at Moreton Bay. By 1839 only 107 prisoners remained in the settlement. In Backhouse and Walker’s recollections, ‘at the time when the convict rule was supposed to be nigh its end, Brisbane existed almost only in name’:

There were no streets, and nothing that could by any stretch of the imagination, be tortured into a town. Fronting the river, adjoining what is now called William Street, stood the modest wooden residence of the Commandant. In its rear was a long row of old rubble buildings for the minor officials and servants immediately attached to him; some of these rooms are still remaining behind an hotel in George Street, close to Telegraph Lane. At some distance further up the river, were the commissariat quarters… Farther on the road to Breakfast Creek for Fortitude Valley then had no name was the house of the clerk of the works. Beyond these and a few temporary huts, there was nothing to indicate a town; and with the exception of the garden and cultivated ground mentioned in “Backhouse’s Journal,” all was “bush.”’

(Coote, pp. 29-30)

John McIntosh, first Chief Constable

The first police force, small as it was, dates back to 1828 when the Colonial Secretary Correspondence lists John McIntosh as the first Chief Constable. McIntosh was transported for life to New South Wales in February 1814 on the General Hewitt and arrived at Moreton Bay in 1826.

Originally from Glasgow, born in 1789, McIntosh, a watch and clock maker by trade was convicted at Berwick, Northumberland in May 1813 and sentenced to transportation for life. Little is known of his life in the colonies until 1826 when, after an unsuccessful term as a Superintendent of Convicts at Liverpool (Sydney), McIntosh was investigated and found guilty of gross irregularities and lost his Ticket of Leave, a form of parole. (Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, 16 Jan 1826, p. 1) Several months later, however, he volunteered to relocate to Moreton Bay as an overseer at the Agricultural Department. (Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay)

Two years after relocating to Moreton Bay McIntosh earned another Ticket of Leave and is listed as a Chief Constable of the local police force. Unlike the remainder of the small force and most of the settlement population, McIntosh was married when he arrived, having obtained permission to marry another convict, Christiana Ferris (a proper spelling of ‘Christana Harris’) in 1824. Chief Constable McIntosh remained in Brisbane until 1833, when he petitioned for replacement and leave to return to Sydney. He died in July 1842 as Chief Constable of the Goulburn Police (Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 12 July 1842, p. 3), just a few months after his wife Christiana was imprisoned for drunkenness at Newcastle Gaol. (New Castle Gaol Entrance Book)

Christiana had her own colourful history. She was born in 1800 and at age 22 she was indicted at the Old Bailey (Middlesex) ‘for feloniously assaulting Joseph Bentley, on the 14 of January, on the King’s Highway, putting him in fear, and taking from his person, and against his will, one brooch, value 15 s., his property.’ (Old Bailey Proceedings Online, www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 10 July 2017, February 1822, trial of CHRISTIANA FERRIS (t18220220-27)). Though charged with violent theft and highway robbery, Christiana was found guilty only of stealing. Still, she was sentenced to transportation for life.

A year after her husband’s death Christiana petitioned for a permission to marry a free man Joseph Nicholson (aka Nicholls), which was denied as on the record she was still married to John McIntosh. The following year, in 1844, she petitioned again and this time the permission was granted. There is no way of determining what happened in the year between January 1844 and 1845, but on 31 January 1845, Christiana married a fellow convict James Broad in East Maitland. (NSW, Registers of Convicts’ Applications to Marry, 1826-1851)

The End of the Convict Police

Replacing John McIntosh at Moreton Bay in 1833 was Richard Bottington, also Bettingten, a convict initially transported in 1818 on the John Berry from Surrey and re-convicted in Sydney in 1827 for bigamy. He was a plumber, painter, and glazier by trade. Three years later Bottington was succeeded by a free man, William Whyte, who was also a Clerk to the Commandant. In 1840, the police force of Brisbane Town consisted of one Chief Constable William Whyte; Bush Constable George Brown (free); four convicts employed as assistant Constables: Francis Black (arrived on the Hadlow), Robert Giles (Exmouth), and W H Sketland ‘or Thompson’ (Sophia), and John Egan.

Following the nineteenth century reforms in the police forces of England, Ireland and Scotland, the Brisbane force was also now responsible for monitoring and curtailing certain behaviours, social decorum, as well as crime. The police was tasked with enforcing trading hours, such as Sunday closing at 10 am. Trading outside of these prescribed hours incurred a £3 penalty. Shortly, the majority of daily activities of the town life were regulated. Penalties ranging from £1 to £20 were introduced for misdemeanours, such as damaging a public building, extinguishing a street lamp, bathing near or within a view of a public wharf, or installing awnings on shops and houses. (Police Act 1838) It is noteworthy that the Act did not provide for imprisonment as a form of alternative punishment. This is mainly due to the absence of judicial and custodial provisions being in place at the time. However, the town did have a Scourger (flogger), who was a convict and resided with the convicts at the barracks until December 1839. (Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822-1860, SLQ, Reel A2.13)

Soon the efficiency and effectiveness of the convict police came under scrutiny. In 1841, a complaint about local shortage of rum alleged it was sold to private individuals straight from the Commissariat Store. The demands for free constables grew louder, especially following a particularly audacious theft. There was a general feeling that there was ‘too much of a fellow-feeling’ in the community. (‘News from the Interior. Moreton Bay’, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 Dec 1842, p. 2) There was a push back against appointing convicts and ex-convicts to the police force as free immigrants started to arrive in large numbers. The penal settlement was closed in 1842, and the Moreton Bay area was thrown open to free settlement, with Brisbane Town as its centre.

PETER ‘DUFF’ MURPHY (1846-1853, resigned)

Layout of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay, 20 Sep 1839, QSA Item ID 659605; Town of Brisbane, Brisbane City Archive 2078

Until 1839, Moreton Bay saw a steady stream of convicts. In 1839, the last draft of convicts, both male and female, landed on the banks of the Brisbane River. These included the first convict policemen. Peter ‘Duff’ Murphy initially arrived into the penal settlement as an assigned servant to Patrick Leslie, a pioneer and grazier from Scotland. In 1846, he returned in a radically new capacity of a District Constable Murphy, Kangaroo Point.

Peter Murphy was born in Dublin in 1806 into a working class, Roman Catholic family, only a few years after yet another failed uprising in 1803, led by United Irishman Robert Emmet, had shaken the capital. Following a series of reorganisations throughout the first decades of the 1800s, Dublin saw its peace and property preserved by the day police during the daylight hours and the watchmen after sundown. Various contemporary accounts depicted the night watchmen as old, infirm and completely unfit for the job ‘always prepared to allow a prisoner to escape on the production of half-a-crown.’ Peter Murphy’s first brush with the law came at the age of 16, when he was apprehended for theft of clothes. (‘Police Intelligence’, Saunder’s News-Letter, 28 Jul 1821, p. 2) Murphy, in company of Jonathan Brennan, was witnessed fencing a military plaid-coat, a cotton dressing gown, a pair of leather breeches, a pair of pantaloons, and two handkerchiefs. Three years later, in 1825, Peter Murphy, alias Duff, was at the Newgate Prison, Dublin awaiting trial for burglary and felony. (The Dublin Morning Register, 24 Jun 1825, p. 2) The outcome of that trial is unknown, however, we do know that a year later, on the night of 3 June 1826, Peter with a new accomplice, a 13 year old boy named Christopher Monks, got indicted for having ‘barbarously and feloniously entered the house of Pat. Barnewall, Spring-gardens, Newcomen-bridge, and taken therefrom certain articles, the property of Mr Barnewall (also Barnwell), and also some clothes the property of Miss Anne Frued.’ (The Dublin Morning Register, 21 Jun 1826, p. 3)

As the boys tried to escape with the clothes, one of the residents was woken up by the noise and raised alarm. The night watchmen John Waker and John Graham on duty in the area gave chase. Murphy and Monks abandoned their loot during the run. At the trial McKane, another resident, testified that he recognised Murphy, as they both lived in the area. The arresting watchman Graham testified that he saw the two prisoners running across a field from the gardens, upon catching up with Duff, alias Murphy, he ‘immediately pulled a pistol from under his coat, presented it at witness, and told him to stand back or he would blow the contents of it through him.’ (Ibid) The jury returned the verdict against both prisoners, as guilty of felony, and not guilty of burglary; ‘sentence – to be transported for life.’

Murphy’s transportation record shows he was indicted and convicted of street robbery in the Dublin City Court and sentenced for transportation to Australia for the period of his natural life. Murphy made his passage over on a convict ship Countess of Harcourt (4). She sailed from Dublin on 14 February 1827 and, following a 134 days’ journey, arrived at Sydney on 28 June 1827, along with 22 transported countrymen (eight of them lifers) he arrived in Sydney. Murphy, a common Irish surname, was supplemented by “Duff” which derives from Gaelic dubh, dark or black, inspired by Murphy’s complexion. According to his transportation record, Murphy had brown hair and brown eyes with a distinct scar across the centre of his forehead.

Ten years later, in 1838, he was assigned as a servant man to Patrick Leslie, a pioneer and a grazier who arrived in Sydney from Scotland four years previously. Murphy distinguished himself during the Darling Downs expedition on a number of occasions, repelling attacks by the local Aboriginal tribes. It was the assistance Peter lent Leslie that secured him his pardon.’ (The Queenslander, 20 Feb 1892) In his diary Leslie described Murphy as ‘the best plucked fellow’. As he returned to Sydney, Leslie asked the then Governor, Sir George Gipps, to grant Murphy a ticket-of-leave in gratitude for his services before the expiration of the sentence, which was of course, life. Murphy was granted ticket-of-leave on 13 June 1842. The conditions of parole allowed Murphy to stay within the Moreton Bay district. Nevertheless, for the duration of the year, he resided in Port Macquarie where he performed duties of District Constable. This he has done exceedingly well, as ‘The Country News’ in the Australasian from 28 May 1842 hinted at Murphy’s promotion to the Chief Constableship at Moreton Bay. (p. 3) It will be some years before Murphy will receive the honour, however.

On 29 November 1842, in presence of Mary Anne and William Tyrell, Peter Murphy married Catherine Thompson at St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Sydney. (Marriage Certificate, 1266/1842 V18421266 91) Peter and Catherine went on to have five living children and five boys and a girl that died in infancy. Margaret (1844), Elizabeth (1846), Peter (1848), John (1850), and Edward Joseph (1853) were born and baptised in Moreton Bay. (Death Certificate, C1472) On 31 December 1846, Murphy received a conditional pardon (No 1225) three years after he was granted ticket-of-leave. The pardon’s conditions allowed Murphy freedom of movement in all parts of the world, except the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland ‘then this pardon shell thenceforth be and become wholly void, as by Her Majesty’s Commands expressly limited and directed’.

By the time Murphy and his family reached Brisbane, Moreton Bay was opened for free settlement. All convicts except 39 men were removed. The settlement continued expanding and its administrative apparatus grew in complexity, such as establishment of the Courts of Petty Sessions in 1846, the first Circuit Court and the first bank in 1850. Between 1846 and 1850, Brisbane’s population more than tripled from just under a 1,000 to 3,150 inhabitants. (ABS) As the population expanded so did the town landscape. In the mid-1840s a third township emerged, Kangaroo Point. Here land sold at £5 pounds per acre. In comparison, building allotments in North and South Brisbane sold for twenty times the price. Constable Peter Murphy and his family (including two daughters, Margaret and Elizabeth) owned two of those allotments in Kangaroo Point, one conveniently located across from a lockup.

As evidenced by court reports reprinted in the Moreton Bay Courier, most of the cases prosecuted by District Constable Murphy were property offences and offences against good order such as drunkenness or indecent exposure. The former significantly outnumbered the latter. William Murray was summoned to appear before the Magistrates on 20 July 1847, ‘charged with indecently exposing his person at Kangaroo Point on the previous day. The defendant did not appear, and the case being substantiated by Constable Murphy, he was fined £5, which was subsequently paid.’ (‘Indecent Exposure’, Moreton Bay Courier, 31 Jul 1847, p. 3)

In July 1850, Murphy investigated and prosecuted an interesting case of a house robbery, where he got to apply his forensic skills. On the night of 15 July 1850, the house of a man named Duffy in Kangaroo Point was burglarised. The thief entered through the window and stole a one pound note and three penny pieces. Murphy’s suspicion fell on a ticket-of-leave holder Isaac Thomlin (convict ship Mount Elphinestone). By an odd chance he found the man in question at the Police Office, where he was making a request to be allowed a pass to remain in Brisbane (all ticket-of-leave men and women were not free to move around until pardoned). Murphy decided to search him. He found the notes which was positively identified by Mrs Duffy ‘by the peculiar way it was folded and by some remarkable stains on it’. Murphy also examined Thomlin’s boots which he matched to a boot print he found near Duffy’s house. The boot was missing a nail and left a characteristic impression in the soft soil. The defendant was sentenced to six months in an ironed gang. (‘House Robbery’, Moreton Bay Courier, 20 Jul 1850, p. 2).

In 1850, the Brisbane Police also underwent organisation changes and expanded; the police force now comprised of a chief constable, a district constable in Kangaroo Point, 8 constables (increased to 11 in 1853 per ‘Domestic Intelligence’, Moreton Bay Courier, 25 Jun 1853, p. 3), a clerk and a watch-house keeper. The Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in New South Wales (14 Vic, No.38) provided for establishment of a colonial police force headed by an Inspector General supported by a network of provincial inspectors. The proclamation of the act ended locally organised police forces in New South Wales and the domination of the police force by the magistracy.

In January, Samuel Sneyd succeeded Chief Constable William Fitzpatrick, who was dismissed from the force in the end of 1849. As Sneyd took over, the cases for breach of conduct of the police appeared more regularly in the local newspapers. In 1853, Murphy was charged with being drunk twice, on 21 January 1853 (‘Charges against Constable’, Moreton Bay Courier, 22 Jan 1853, p. 2) and in June, when he was found drunk at the ferry wharf, Kangaroo Point. As this was a repeat offence, the Bench sentenced him to pay a fine of £5. Brisbane Police annual pay at the time was £125 for Chief Constable, £95 16s 3d p.a. District Constable, or roughly £1 8s per week, and £86 13s 9d p.a. for Constable. (Moreton Bay Courier, 25 Jun 1853, p. 3) Murphy tendered his resignation following the hearing, which was accepted. (Moreton Bay Courier, 18 Jun 1853, p. 2)

Murphy’s third son, Edward Joseph, was born the same year. Land sale records and Police Court coverage for Ipswich show that Murphy relocated to the town and 1860s onwards presided over the local Police Court. The cadastral map of Brisbane listed ‘P Murphy’ as the owner of two allotments in Kangaroo Point, 27 and 32, as late as 1874. Peter ‘Duff’ Murphy died on 6 April 1878 at Charters Towers aged 72, ‘a highly respected colonist’. (Brisbane Courier, 13 May 1878, p. 2)

SAMUEL SNEYD (1850-1859, resigned)

Town of Brisbane, 1844. Brisbane City Archive ID 2078; Map Brisbane 1858 showing town Boundary, 1859. BCA ID P005

A new Police Force was organised in 1850. The Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in New South Wales (14 Vic, No.38) provided for establishment of a colonial police force headed by an Inspector General and maintained by a network of provincial inspectors. The proclamation of the act ended locally organised police forces in New South Wales and the domination of the police force by the magistracy, though not for very long. The following year, the Act for the Regulation of the Police Force 1850 was disallowed and replaced by the Police Regulations Act 1852, reinstating rural police firmly under control of their magistrates’ benches. A local Chief Constable continued to receive his orders from the Police Magistrate.

New Chief Constable, Samuel Sneyd, was brought over to replace William Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick in turn had replaced Chief Constable William Whyte with his convict policemen in 1843, the same year Captain John Clements Wickham was appointed a permanent Police Magistrate for Brisbane. Four free constables, Martin Higgins, Jeremiah Scanlan, James Ramsey and John McGrath replaced ex-convict policemen Francis Black (Hadlow), Robert Giles (Exmouth), and W H Sketland ‘or Thompson’ (Sophia), and John Egan. Less than a month before his dismissal, Fitzpatrick was ‘severely censured’ by the police magistrate for not responding to a call of alarm (he stayed in bed due to a late shift the night before) raised by a local squatter concerned about a missing bullock and perceived threats made by a tribe camped near Kangaroo Point. The military assembled along with a few constables, shots were fired resulting in flesh wounds to four tribesmen which were treated at the hospital the next day. The missing bullock turned up a short time after the affray. (‘Investigation Respecting the Affray with the Aborigines’, Moreton Bay Courier, 8 Dec 1849, p. 2)

The new police force was comprised of Chief Constable Samuel Sneyd, a newly added District Constable in Kangaroo Point (as the population expanded so did the town landscape, including a new township of Kangaroo point), 8 constables, a clerk and watch-house keeper, Constable John Booth. The District Constable for the new township was the former lifer from Dublin, Peter Duff Murphy. Shortly, the number was deemed insufficient and the force was increased by four ordinary constables. There were no designated Detective Constables until the centralisation of the colonial force in 1864.

Samuel Sneyd immigrated to the colonies from England. He was the first-born child of Baptists Samuel Sneyd, a grocer, and Elizabeth Margaret Oliver. He was born in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England on 15 March 1811, and was followed by his sister Mary in 1814, and brother James in 1818. (‘Samuel Sneyd’, Family Pages) In 1832, at the age of 22, Sneyd came to Australia with the “4th of King” regiment. In the early days, he was selected as one of the picked men from the regiment to suppress bushranging in the colony. While in the Mounted Police he rose to the position of sergeant-major of the Goulburn Division.’ (‘Death of Mr Samuel Sneyd’, Queenslander, 11 Jul 1885, p. 67) On 13 February 1837, Sneyd, in command of the Woollongong Mounted Police, married Miss Kitty Mulcahy, originally of Black Rock near Cork, Ireland, emigrant per ship James Pattison. (Sydney Monitor, 24 Feb 1837, p. 3) They went on to have nine children. Widowed in 1858, Sneyd remarried to Margaret Hyland and had six more children, five of who grew into adulthood.

Overall, Sneyd worked with the police in New South Wales for twenty years, having been stationed in Wollongong, Bowen’s Hollow, and Goulburn among other places. At the time of appointment to the Brisbane Police in January 1850, Sneyd was in Sydney and his family in Goulburn, where he was stationed. Consequently, he had to petition the Colonial Secretary for additional time to move his family to Brisbane, which was approved. In the interim, District Constable Murphy served as an acting Chief Constable.

By 1850, Brisbane population was about 3150 with a police contingent of 9 policemen, 8 ordinary and one district. Covering both day and night shifts, on average, police to population ratio at the time was roughly one constable per 1000 inhabitants. Understaffed and underpaid, the small force struggled with the round the clock duty which resulted in lapses in discipline. Prior to Separation, these men also performed escort duty to Sydney about two to three times a year after the Assizes, when the prisoners had to be transported to serve their custodial sentences. This practice stopped after Separation as the prisoners were kept at the local jail. It is noteworthy, that the escort duty was never performed by land but always by water.

On 5 January 1850, the Moreton Bay Courier printed an inquiry that was brought before the Bench. A complaint was made to the Police Magistrate by District Inspector Murphy, an acting Chief, that Constables Hore and Sparkes had neglected their duty and been intoxicated. ‘The charges having been proved on oath, and corroborated by the testimony of Dr Ballow, Mr Dowes, and other witnesses, both constables were dismissed [from] the force. It appeared that Sparkes had confined a man in the watchhouse for drunkenness, where he himself was more intoxicated than the prisoner.’ (‘Constables Dismissed. Domestic Intelligence’, MBC, 5 Jan 1850, p. 2) As evidenced by rising prosecutions for breach of conduct in the police, Chief Constable Sneyd was a meticulous man fond of rules and regulations. His testimony to the Select Committee on the Police in 1860, showed that he required the applicants to his force to provide testimonials of character and a doctor’s certificate of good health. Sneyd is also frequently seen expressing the desire the police be trained in drill and use of fire arms, however, he advocated against military discipline.

Similar to the Metropolitan Police force in Dublin and London at the time, uniforms of the local police included stocks, a rigid leather collar meant to ensure the right posture. These were uncomfortable and widely lamented. Sneyd openly deemed these ‘detrimental to the man’s health’. (Mr Sneyd, 11 Jul 1860, ‘Select Committee on Police’, QVP 1860, p. 19 [553]) The rest of the uniform issued comprised of a coat; full-dress trousers; white duck trousers, white caps; Wellington boots; Scotch twill shirts; three-stripe silver chevrons and great coats. (‘Clothing, Foot Police, Police Force’, QGG, 29 Dec 1860, p. 535)

During Sneyd’s term, the police contingent slowly increased:

in Fortitude Valley, there was one district constable and one ordinary constable; in south Brisbane there were three ordinary constables, and one district constable; at Kangaroo point one ordinary constable; in North Brisbane one Chief Constable, two mounted, and one ordinary constable acting as Lock-up keeper, and five more performing street duty; these were employed two by day and three by night. The day constables were on duty from 5am to 10pm; the night constables being on duty from 10pm to 5 am; the Lock-up keeper was continually on duty at the Lock-up, having also the charge of the Police Office. The mounted constables were employed in patrolling about the suburbs and in the district generally. At South Brisbane, there was one constable continually on duty day and night [as of November 1859]. The district constables had to patrol about the Western Suburbs and Bulimba twice a week; the Fortitude Valley district constable patrolled about Kedron Brook and the German Station twice a week; the man at Kangaroo Point was continually on duty. There were two mounted men whose duty it was to execute all Warrants and Summonses in the bush for the Police District of Brisbane and to make patrols occasionally to the Logan and Albert Rivers and extreme parts of the District. There were two for Logan District and the exterior, who patrolled once a week. (Mr Sneyd, 11 Jul 1860, ‘Select Committee on Police’, QVP 1860, p. 17 [551])

Between 1856 and 1859, Brisbane Police district population increased from 5,844 to 6,051 (Pugh’s Almanac 1860-61). The numbers only reflect the European presence, as the Indigenous population were marginalised, displaced from the settlement. Between June 1859 and June 1860, there were 38 offenders tried at the Supreme Court, including on Circuit, of which 13 per cent of the defendants were Aborigines (all guilty verdicts with hard labour custodial sentence). The list of summary cases tried at the Brisbane bench between Sep 1857-30 Sep 1858 does not provide details such as race, having said that due to concerted efforts of the Mounted Police, the Volunteer Force and the squatters to push the frontier, the Indigenous presence in Brisbane town proper was quite small. Below is the breakdown of the summary offences disposed of by the Police Magistrate:

- Common Assaults 40

- Embezzlement 20

- Masters and Servants Act 78

- Rogues and Vagabonds 71

- Drunk and disorderly 337

- Indecent exposure 4

(PA 1859, p. 41)

The significant number of drunk and disorderly arrests is hardly a unique or isolated incident. Consistently, ‘drunkenness’ or ‘drunk and disorderly’ are amongst the most numerous offences in police statistics across the urban forces in the colonies and England, and Ireland. Having said that, the handful of night and day Brisbane ordinary constables were kept busy indeed, as there was a total of 615 misdemeanours prosecuted in that year.

(Early View of Queen Street, Brisbane ca. 1859. SQL Neg 8299; Queen Street, 1868. John Oxley Library ID 36322)

In his ‘reflections’, a local resident writing under a pseudonym ‘A Stroller’, offered the following account titled ‘The Morals of Brisbane’, printed in the Moreton Bay Courier in November 1858:

SCENE I – Top of Queen Street. Time 10 o’clock at night. Two policemen talking.

No 1. – “I say Jem, see anybody about.”

No 2. – “No Tom, M’Adam’s cat has just run round Brookes’ corner.”

No 1. – “I’ll bet a tanner [sic] he is gone a wooing.”

No 2. – “Bad luck on him to set such an example. Seen anybody herring-boning?”

No 1. – “Out of all character, Tom, people are reforming. The quiet taste of the inhabitants makes our sheet look dull in the morning. Here will soon be nothing to do. Ever since Mr. Brown [William Anthony Brown, the Sherriff and the Police Magistrate] took the chair at the Teetotal meeting, people are afraid to get spicy with Old Tom, or kick up Bob’s-a-dying though the effects of a nobbler. Whatever shall we do, Tom, if the folks won’t get drunk?”

No 2. – “Don’t be alarmed! Hark! Hear you that noise?”

No 1. – “I hear it. By teetotalism, I swear, it’s a fellow three sheets in the wind.”

A half-drunken man staggers along, singing.

“I’m off, I’m off, to Burrendong.

To dig for a tinful of gold.”

No 1. – “Oh yes, my boy, just come along

I think you’ll find yourself sold.”

No 2. – Nabbing him, “we’ll find you a Burrendong.”

Escorts the singer to the lock-up, the unfortunate wight singing –

“I’m going, I’m going,

Where the beetles crawl;

From thence to where the breaks

Will me overhaul.”

During the rest of the night the only noises witnessed by ‘A Stroller’ were ‘violent barkings of stray dogs, not yet disciplined into our new regulations’.

SCENE – Next Morning – The Police Court.

Mr Brown: How many cases are there?

Mr Sneyd: One, your worship.

Mr Brown: Who is the prisoner?

Mr Sneyd: A man who says he is off to Burrendong.

Mr Brown: Let him go then. Is that all the business?

Mr Sneyd: Yes, your worship.

Mr Brown: There really is nothing worth coming to the Court for. I congratulate the inhabitants of Brisbane on their orderly behaviour. If any body else should get drunk during the next week you can let me know. I shall be at home.

The worthy magistrate made his exit. Mr Sneyd rolled up his charge sheet. Mr May [the clerk] adjusted his spectacles. The policemen engaged themselves in keeping the flies from the sausage shop; and the waiters at the public-houses put on mourning; and in many instances the shutters of grog-shops were put up.

The satirical piece cheekily concludes with, ‘this is my report…It is not likely to be true, as it is only the fudge of A STROLLER.’ (‘The Morals of Brisbane’, MBC, 27 Nov 1858, p. 2)

A year later, Chief Constable Sneyd retired from the Brisbane Police and took up a post of “a gaoler” at the Brisbane Gaol. Sneyd was presented with a gold watch and gold Albert chain and key by the Brisbane Police force, as an expression of their regard and respect for him. The watch was a hunter lever, and bore the following inscription on the inside of the case, ‘Presented to Mr. S. Sneyd, Chief Constable of the Brisbane police force, by the men serving under him, as a token of respect upon his retiring from the service Dec. 15, 1859.’ (MBC, 17 Dec 1859, p. 2) At a conclusion of Sneyd’s term, the existing pay of ordinary and district constables increased (from 2s 3d per day in 1848 to 5s 6d per day in 1859 for ordinary constables) but it was still deemed insufficient. Sneyd testified to the Select Committee of Police in 1860 that the pay ought to be increased to the Sydney Metropolitan Police level of 6s 6d per day for ordinary police, as ‘a good many men have left and joined the police force in Sydney on account of the higher pay.’ (Ibid, 18 [552])

Chief Constable Thomas Quirk then took over the force. In mid-1860, it comprised 1 Inspector; 2 Sergeants; 2 Lock-up keepers (North and South Brisbane); 9 Ordinary Constables (North and South Brisbane, Kangaroo Point and Fortitude Valley); 4 Mounted Constables (2 attached to the Government House); 1 Foot Constable (night sentry, Government House); 4 Ordinary Constables as messengers attached to the various colonial administrative offices.

(Early biographical details of Chief Constable Samuel Sneyd courtesy of Lisa Jones, Curator of Queensland Police Museum)

ALFRED SAMUEL WRIGHT (1850-1864, Discharged)

Alfred Samuel Wright was born in Butters Place, Southwark, in 1820 to Samuel Bridgeman Wright, wool stapler, and Mary Ann Morgan (London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917, p. 261). Before making his journey to the Australian colonies, Wright, a warehouse man, married Matilda Bryant on 10 March 1844, at the Protestant Church of Saint James, Bermondsey, London. The ceremony was conducted by Thomas Ridley in the presence of John Wilcock and Joseph Wheeler. Matilda was born on 13 September 1826 to Edward Bryant and Henrietta Elizabeth Harriet Page in Ashburton, Devon (London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921, p. 135).

Following a six-month journey, Alfred and Matilda Wright arrived with their three children, Matilda Clara Hannah, Edward Alfred and Emma Sophia Chaseley (she was born on the ship, Birth Reg BP0307), in Brisbane in May 1849. (Registers of Immigrant Ships’ Arrivals, Series ID 13086; Roll M1696, QSA). Matilda’s sister, Elizabeth Dickens, also journeyed to Moreton Bay with her husband Thomas and his siblings. In 1859, a decade after their arrival, Matilda’s niece, Elizabeth Rose Welsh (neé Dickens) opened a school for young ladies (Meiklejohn, First Families 2001).

Shortly after settling in Brisbane, in June 1850, Alfred Samuel Wright joined the local police. This was only a couple of months after Chief Constable Samuel Sneyd had taken over the newly re-organised force (The Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in New South Wales 14 Vic, No. 38). At the time, the police force comprised of a Chief Constable, a District Constable, six to 11 Constables (including one at Kangaroo Point), a clerk and a watch-house keeper. The Brisbane gaol was opened the same year providing facilities for custodial punishment. The first ‘gaoler’ was Martin Feeney, who had ‘served in the British army for 28 years, before becoming a sergeant-major of the mounted police force in Sydney for 11 years. His wife Maria held a position of a matron of the Brisbane gaol. The gaol quickly acquired its first inmates – 16 by mid-January [1850]. (Ross Johnston, Brisbane-The First Thirty Years, p. 169)

The Wright family’s first year in Brisbane was marred by the death of their five-year-old son, Edward Alfred Wright, in November 1850. Edward was playing with other children at the back of the Commissariat Store, ‘when turning round the parapet surmounting the wall of the deep area that surrounds the building, he lost his balance and fell to the bottom, a distance of some eighteen to twenty feet’ (‘Fatal Accident’, MBC, 4 Nov 1850, p. 1). The accident was witnessed by a servant woman of the Chief Constable of the police. She summoned assistance and Edward was carried to the house of Chief Constable Sneyd. Drs Hobbs and Cannan attended soon after, but the boy died that night without ever regaining consciousness. The couple went on to have seven more children, a total of 5 girls and 6 boys. In a tragic coincidence, another boy also named Edward Alfred born in 1867, died in infancy (Wright QP Personnel File).

According to the surviving court records, the majority of cases Constable Wright dealt with during his time with the Brisbane Police were related to the sale or consumption of alcohol. In April 1852, Constable Wright together with Constable Swinburne appeared before the Brisbane Bench to answer the charge of one Victor Godoy. They were charged with neglecting their duty by going into and remaining in a public-house . The court heard that when on duty (or in uniform), police were prohibited from entering a public-house. The magistrate found that the constables had gone into the house in the discharge of their duty, and therefore dismissed the case (MBC 24 Apr 1852, p. 2). Alcohol related prosecutions dominated bench books all through the nineteenth century. Constable Wright’s charges against Roger Eaton of being drunk and using profane language in Queens Street would be typical of his daily work. Eaton pleaded guilty to the charge and was fined 10 shillings (MBC 16 Oct 1852, p. 2).

In another case, Joseph Antonio, ‘an old sinner’, was charged at the Brisbane Police Office with vagrancy. According to the court proceedings, the defendant had only finished serving three months imprisonment with hard labour a day earlier. Antonio was under sentence of the Ipswich Bench, for begging in the streets. On the afternoon of the day he was discharged, he went into the shop of Mr Cooling at North Brisbane where ‘he represented himself as an unfortunate who had just arrived in the colony and had lost his wife and family. He spoke in French, [pretending] he did not understand English, and Mrs Cooling, taking compassion on him, gave him a note to a magistrate, but instead of making use of that he went away and got drunk, in which state he was apprehended by Constable Wright’ (MBC 8 Apr 1854, p. 2). Antonio was sentenced to six months with hard labour.

The following month, Constable Wright was present during another interesting case. Three seamen off the Himalaya who had recently served a month’s imprisonment for absconding from that vessel, were again brought up before the Brisbane Bench for refusing to return to duty. They were sentenced to be imprisoned for one month, or until the ship sailed:

The Water Police Magistrate, Mr Duncan, had scarcely pronounced this sentence, when one of the prisoners, Edmund Henry Davis, took a stone out of his pocket and threw with great force at Magistrate Duncan…District Constable Anderson and Constable Wright, the lockup keeper, proved that the prisoner had no stone in his possession when confined. He must have obtained the missile from the ruinous walls of his cell, many of those receptacles being so dilapidated that they were not used at all (MBC 6 May 1854, p. 2).

Constable Wright gave evidence as to the insecurity of the cells, ‘which showed that it was time the new ones were built’.

One of the most infamous cases of the decade, however, involved Wright’s wife, Matilda. As no women served in the police force until the twentieth century, the wives of jail wardens or lockup keepers often served as female searchers or matrons. On 22 May 1852, Matilda Wright, a female searcher at the Lockup, was deposed in the notorious case of Jane Ellis. Mrs Ellis, the wife of warder, stood indicted for having unlawfully and maliciously committed a series of assaults on Jane McEvoy, ‘an infant of tender years’ (MBC 22 May 1852). Witnesses stated that the girl was ‘one mess of sores and congealed blood’ from her loins to the back of her knees. According to the trial coverage, the abuse began seven years earlier:

Isabella, aged about 15, was routinely stripped, strung up by her arms so only her toes touched the ground, and was beaten with a stick or whip for long periods. Isabella ran away and hid under a neighbour’s house for 24 hours. Once she reappeared, neighbours took her to the Chief Constable and he had a doctor look at her injuries… The jury after some deliberations found Jane Ellis guilty on both counts, she received a sentence of 14-months imprisonment for the first and 10 months for the second. The prisoner was committed to the custody of the Sheriff, and she was sent to serve her time at the Parramatta Gaol in New South Wales (Lisa Jones in Dukova, Policing Colonial Brisbane, UQP 2020).

In November 1859, Alfred applied for the office of the Chief Constable, having served as a constable and a lockup-keeper. The other candidate for the role was Mr Thomas Francis Quirk, previously inspector in charge of the Sydney District Police. The bench carefully considered the claims and testimonials of Wright and Quirk, and appointed Mr Quick to the office (MBC 26 Nov 1859, p. 2). The month after Quick’s appointment, the Police Department relocated from the old Convict Barracks to the old gaol in Queen Street, having doubled in size since 1850. In June 1859, the Brisbane police force comprised of a Chief Constable, 3 Sergeants and 18 Constables.

Between 1856 and 1861, Queensland’s urban population also increased by almost 40%, putting more pressure on the small police force (Table XVIII, Report – Census, 1861, p. vii). In May 1862, Colonial Secretary Robert Herbert put forth a bill proposing to consolidate the laws relating to the police. The most significant change to the existing organisation was a recommendation to appoint a paid superintendent of police for the colony; the Colonial Secretary provided justification for the organisational reform arguing that ‘by having an officer responsible for the management of [police] department, a saving of several thousand pounds, would he felt sure, be effected in the supply of stores, the pay of constables, and in many other matters.’ An entry level constable received 5s 6p per day, and those of a higher grade were remunerated at 6s 3p per day, the rate was fixed when the ‘gold fields first broke out, when everything was very dear’ (‘Police Regulation Bill’, Legislative Assembly, Record of the Proceedings of the Queensland Parliament, 20 May 1862). Due to the rapid colonial growth and the parallel expansion of the force, by 1862, expenses amounted to a staggering £50,000.

Colonial Secretary Herbert government’s proposed bill under which these reforms would be instigated also suggests that possibility for collusion and nepotism were rampant under the existing organisation, for ‘as long as [the Constable] was well behaved in his own district, and pleased his own magistrate, he had nothing to fear.’ The Opposition, however, was concerned that the proposed changes would ‘throw more patronage into the hands of the Government’ instead. Local and overseas examples indicated that the corruption of local magistracy was widespread. In 1812, the Dublin citizens presented a petition to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland complaining about the police magistrates’ connections with gambling houses. The letter also exposed the magistrates’ ‘improper use of police horses and supplies, and employment of paid constables as “domestic and menial Servants, the Police institution has been charged as if they were respectively effective Police Men doing duty”’ (Dukova, 2016, p. 49). In Queensland, a similar practice was highlighted during the Commission into Management and Working of the Police Force, 1868-69. Inspector Lewis testified ‘that every police magistrate in the colony employed constables for their own purposes: ‘As I understand, they looked upon it as a right to have a man, as an orderly, to look after their horses and trap, and [on] messages, and to whatever rounds was wanted’ (J. A. Lewis, ‘On the Management and Working of the Police Force’, Commission into Management and Working of the Police Force, 1868-69, p. 49, QPM). William Anthony Brown, Brisbane Police Magistrate, ‘had one or two police constables for his private service, who, the evidence showed, did not do any police duty’ (Dukova, 2016, p. 50). The men were remunerated from the police resources by being paid a night allowance (‘D.T. Seymour’, Commission, 1868-9’, p. 16). Brown had been appointed as Brisbane Police Magistrate in 1857. At that time, the Brisbane Police Magistrate’s role also encompassed the role of Sheriff and Superintendent of police (‘Police Regulation Bill’, Legislative Assembly, Record of the Proceedings, 20 May 1862).

On 1 January 1864, the new Queensland Police Act was promulgated. Despite the introduction of a new Police Act, there was no clear magistracy reform. The magistrates retained their powers as Inspectors, meaning that an official could effectively act as a prosecutor and judge in the same case, while having full command over the rank and file police.

Wright transitioned into the new organisation along with the rest of the Brisbane Police. The Register of Members of the Police Force describes him as 5’6” tall (one inch under the minimum gazetted height, no doubt an exception made due to his previous service), of dark complexion with hazel eyes and brown hair. (Register of Members of the Police Force) Wright’s time with the Queensland Police Force was brief, as per the Queensland Police Gazette, he was discharged on 7 December 1864 (Queensland Police Gazette 1864, p. 24).

Alfred Samuel Wright was later an assistant bailiff under Mr Hingston, the city rates collector (Brisbane Courier, 11 Apr 1866, pp. 2-3). He died on 22 August 1894, at his residence in Richmond Terrace, New Farm and was buried at the Toowong Cemetery, grave location 1-94-18 (BC, 24 Aug 1894, p. 1). Matilda outlived Alfred by 16 years and died at their residence as well, on 2 April 1910 (Australia Death Index, B012438).

REFERENCES

PRIMARY SOURCES

Act for the Regulation of the Police Force in New South Wales of 1850 (14 Vic No.38).

Act for the Regulation of the Police Force 1852 (16 Vic No 33).

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population by sex, state and territories, 31 December, 1788 onwards. http://www.abs.gov.au/.

Brisbane City Council Archives, Map 1859 Brisbane Town Boundary, Resource Identifier BCAP005.

Brisbane City Council Archives, Title Maps, Early Brisbane Plans by Surveyor Henry Wade, 1844, Call Number BCA2078.

Commission into Management and Working of the Police Force, 1868-69.

Death Certificate C1472, https://www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/, accessed 8 September 2018.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland: Early view of Queen Street, Brisbane, ca. 1859, Negative No. 8298.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland: Queen Street, Brisbane, ca. 1868, Negative No. 36322.

London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917.

London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921.

Martens, C., Copy of a sketch by Conrad Martens (1801–1878) of the Ferry from the South Brisbane reach 1850, Royal Historical Society Queensland, Photographic Collection, P53277, a digital copy of P4415.

National Archives, Kew, London, Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868, p. 53. Accessed via ancestry.com.au.

New South Wales State Archives: NRS 12212 Convicts Applications to Marry, 1825 to 1851.

New South Wales State Archives: NRS12188 Convict Indents, 1788 to 1842. ‘Peter Murphy Bound Indentures 1827’.

New South Wales State Archives: Conditional Pardon NSW 31 Dec 1847, Convict Registers of Conditional and Absolute Pardons, 1788 to 1870, p. 384.

New South Wales State Archives: NRS 2373 Entrance Book (Newcastle Gaol), 1840 to 1848.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 10 July 2017, February 1822, trial of CHRISTIANA FERRIS (t18220220-27).

Police Act 1838 (2 Vic No 2).

Police Act 1863 (27 Vic No 11).

‘Police Regulation Bill’, Legislative Assembly, Record of the Proceedings of the Queensland Parliament, 20 May 1862

Pugh, T., Pugh’s Almanac, Directory and Law Calendar for 1859 and 1860, General Printing Office, Brisbane. Available online at: http://www.textqueensland.com.au/pughs/title.

Queensland Government Data, Cadastral Map of Brisbane, 1858, Kangaroo Point.

Queensland Government Gazette, 29 Dec 1860, p. 535. ‘Clothing, Foot Police, Police Force’.

Queensland Police Gazette 1864, p. 24

Queensland State Archives: Digital Image ID 5236, Plan of Female Factory, Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay, 1837.

Queensland State Archives: Digital Image ID 5211, Layout of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay, 20 Sep 1839.

Queensland State Archives: Digital Image ID 5210, Layout of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay, c 1838.

Queensland State Archives: Digital Image ID 5225, Plan of Commissariat Store, Moreton Bay, 1838.

Queensland State Archives: Item ID 869689, Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay.

Queensland State Archives: Series ID 13086, Registers of Immigrant Ships’ Arrivals.

Queensland Votes and Proceedings, ‘Select Committee on Police’, 1860.

Register of Members of the Police Force.

State Library of New South Wales, Barney, G., Map of Brisbane Town, Moreton Bay 1839 (cartographic material)/G. W. Barney.

State Library of Queensland, Letters Relating to Moreton Bay and Queensland Received 1822-1860, SLQ, Reel A2.13.

BOOKS

Coote, W., History of Colony of Queensland from 1770 to the year 1881, Vol. 1, William Thorne, Brisbane, 1882.

Dukova, A., A History of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Its Colonial Legacy, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2016.

Dukova, A., Policing Colonial Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2018.

Johnston, W. R., Brisbane, The First Thirty Years, Boolaroong Press, Bowen Hills, Brisbane, 1988.

Jones, L. in Dukova, A., Policing Colonial Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2018.

Reece, B., Exiles from Erin: Convict Lives in Ireland and Australia, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1919.

NEWSPAPERS AND MAGAZINES

Brisbane Courier, 11 Apr 1866, pp. 2-3.

Brisbane Courier, 13 May 1878, p. 2

Brisbane Courier, 24 Aug 1894, p. 1.

Dublin Morning Register, 24 Jun 1825, p. 2.

Dublin Morning Register, 21 Jun 1826, p. 3.

Moreton Bay Courier, 31 Jul 1847, p. 3. ‘Indecent Exposure’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 8 Dec 1849, p. 2. ‘Investigation Respecting the Affray with the Aborigines’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 5 Jan 1850, p. 2. ‘Constables Dismissed. Domestic Intelligence’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 20 Jul 1850, p. 2. ‘House Robbery’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 4 Nov 1850, p. 1. ‘Fatal Accident’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 22 Jan 1853, p. 2. ‘Charges against Constable’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 18 Jun 1853, p. 2.

Moreton Bay Courier, 25 Jun 1853, p. 3. ‘Domestic Intelligence’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 27 Nov 1858, p. 2. ‘The Morals of Brisbane’.

Moreton Bay Courier, 17 Dec 1859, p. 2.

Queenslander, 11 Jul 1885, p. 67. ‘Death of Mr Samuel Sneyd’.

Queenslander, 20 Feb 1892, p. 3.

Saunder’s News-Letter, 28 Jul 1821, p. 2. ‘Police Intelligence’. The British Newspaper Archive.

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 Jan 1826, p. 1.

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 12 July 1842, p. 3.

Sydney Monitor, 24 Feb 1837, p. 3.

Sydney Morning Herald, 12 Dec 1842, p. 2. ‘News from the Interior. Moreton Bay’.

WEBSITES

Cemeteries Search, Brisbane City Council, https://graves.brisbane.qld.gov.au/.

Dukova, A., Policing Colonial Brisbane. https://policingcolonialbrisbane.com/, 2018.

McIntyre, J., Samuel Sneyd, http://www.artpages.com.au/sam_sneyd.html. Accessed 8 September 2018

Wikipedia, History of the Metropolitan Police Service, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Metropolitan_Police_Service, accessed 8 September 2018.