Abstract

The Moreton Bay District, despite its harsh convict origins, frontier violence, and remoteness, became attractive to settlers. The District was officially opened to free settlement early in 1842. The Artemisia arrived in mid-December 1848 carrying the first government assisted free immigrants to Moreton Bay. I was struck by the scarcity of information about this vessel and its passengers. Her cargo of mechanics, labourers, servants, and other workers, was desperately needed, but not much has been written about them. The ‘ordinary’ folk, workers like those of the Artemisia, along with others such as First Nations people, women, and children, are often ‘invisible’ in mainstream historical narratives. Too often in colonial histories there is a preponderance of generalizations, of epic stories and famous men. This project aims to craft an inclusive narrative where the workers and tradesmen, women, and children, of the Artemisia are visible and audible, providing (where possible) personal historical perspectives, experiences, and life stories.

Description

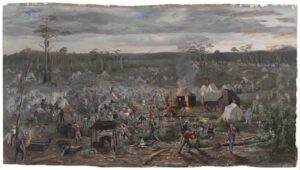

The Artemisia emigrant ship, chartered by the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners, and captained by Captain John Prest Ridley, sailed from London to Plymouth. From there on 15th August 1848, she was bound for Moreton Bay with the first complement of government assisted free immigrants. When the Artemisia reached Moreton Bay between 13th – 16th December 1848 she was too large to sail across the sandbar at the head of the Brisbane River. The passengers then disembarked and travelled up the river on the Raven, a smaller vessel that usually carried cargo and passengers between Brisbane and Ipswich. The Artemisia passengers were accommodated at the prisoner barracks, hospital, and other government buildings in the fledging township of Brisbane.

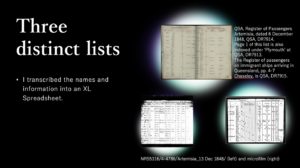

These passengers hold a special place in the annals of Queensland. It is estimated that on board the Artemisia there were 48 married couples, 19 single women and 44 single men, the rest being children and babies although discrepancies in the various numbers of passengers have been noted and have been investigated.

This significant project highlights the passengers from the Artemisia, a diverse group of working people, and brings the first official government assisted free immigrants to Moreton Bay together, striving to provide a richer tapestry of the peoples who populated early Brisbane.

The creation of a database and biographical sketches of the immigrants on the Artemisia has the potential to unlock stories, linkages, and associations that have previously been overlooked and under-researched. It allows these intrepid immigrants to be ‘visible’ to a wider audience. It is hoped that this project will stimulate further research and investigations into Pre-Separation Queensland, give all people a voice, and so provide a fuller and more vibrant understanding of early Queensland.

This project has successfully:

- Located the shipping manifests of the Artemisia

- Created an alphabetical surname listing of all passengers.

- Sought to undertake detailed biographical research on all passengers.

- Drawn interpretations from statistical evidence provided in the compilation of data extracted from the shipping manifests.

- Provided conclusive evidence of inter-relationships and familial relationships of passengers.

- Highlighted the significant social and cultural contributions by these first government assisted free immigrants to the Colony of Queensland.

Acknowledgements

As a Visiting Fellow of the Harry Gentle Resource Centre, I wish to acknowledge the generous assistance and support of the Gentle family. Through the Harry Gentle Resource Centre they assist the ongoing study of early Australian history and promote the study of Social, Economic, Political, Indigenous and Environmental history and innovative methods of research. I am indebted to the Harry Gentle Resource Centre for providing the means for me to research the Artemisia and her passengers, and for the ongoing support from Dr Lee Butterworth, Jan Richardson, Dr Yorick Smaal and Distinguished Professor Mark Finnane. Huge thanks also to the many descendants who have been helpful in supplying information and allowing me to explore further the lives of these first immigrants to Moreton Bay and to know them better.

Dr Dorothy Wickham PhD, MPhil, TPTC, MPHA (Vic & Tas) (Qld)

Dorothy Wickham is a publisher and professional historian with a strong background in archives and education. Since 1990 she has been associated with many historical associations and family history groups, both at a local and state level, showing active participation on many committees, conferences, expos, and newsletters.

She has been closely connected with educational research, historical interpretation, theoretical approaches, and comparative analyses, locating local and regional research within a broader transnational context.

Her educational research projects included Extending Mathematical Understanding (EMU interviews 2003) and Clemente Australia: Building University Collaboration and Capacity for Promoting Educative Justice in Regional Victoria (interviews, reports, lecturing, 2009), the ARC Linkage Project New Play Pedagogies for Teaching and Learning in the Early Years (2015-2017) and ARC Discovery Project Best Practice Framework for Playgroups in Schools (2017-2020).

As a consulting historian she has undertaken many projects including: Collection Policy and Workshops (City of Ballarat 2008); Stage 2 Regional Thematic Study: Mapping the themes of the Central Goldfields’ Heritage Collections (Victorian Department of Community Planning and Development 2012); Skipton Common and Winter Swamp (Ballarat Environmental Network, 2014) and Significance Study of Ballarat Catholic Diocesan Historical Commission Collection (2017).

Dorothy is vitally interested in colonial, welfare, goldfields, feminist and Eureka history, and has written or co-authored over 20 titles including The Eureka Encyclopaedia (Winner Victorian Community History Awards 2005) and Women on the Diggings: Ballarat 1854 (Commended 2010), Freemasons of the Goldfields: 1853-2013 (Shortlisted 2013), Pay Dirt: Hidden Gold. New Discoveries Victorian Goldfields (2018), Women of Substance (2021), and Refuge, Rescue & Reform: Voices of Suffering and Survival (2024). Dorothy is an administrator of the Eurekapedia.org Wiki hosted by Ballarat Reform League and funded by the Vera Moore Foundation.

Locating the Passengers

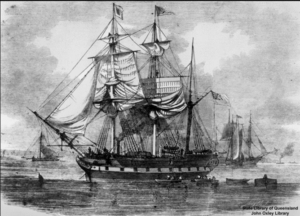

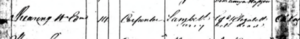

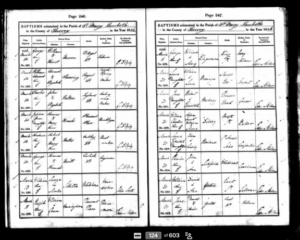

I began this project by locating the shipping manifests of the Artemisia. There were at least three distinctly different original records. It is generally accepted that when a ship (or plane) arrives or leaves a destination, the names of passengers are sought and checked. It appears that this was the case in the 1840s, as it is today. Each list was set out somewhat differently and in a different handwriting, with slightly different information on each.

I created a consolidated spreadsheet arranged alphabetically by surname. Prior to the creation of a consolidated spreadsheet, limited information available about the passengers on the Artemisia was in index form only.

The current indexes were extremely useful to those wishing to locate an ancestor on a particular vessel that arrived in Moreton Bay at a particular date. However, the Queensland State Archives, issued the following warning: Please note: due to the difficulty of deciphering handwriting, names may have been indexed differently to how the name is currently spelt. Variations of spelling should be considered. The content of online indexes has been sourced directly from original records. The Queensland index is arranged (alphabetically) but in separate parts, A-Z, owing to the sheer volume of entries. It provides the names, age, ship, and date of arrival only.[1] The New South Wales Archives also provide Assisted Immigrant Passenger Lists 1828-1896, a useful index for researchers. This can be found on Ancestry.[2] Indexes lead to digital images of the shipping lists and these digital images of original records provide excellent and more comprehensive information.[3]

[1] https://www.data.qld.gov.au/dataset/assisted-immigration-1848-to-1912 accessed Saturday 3 February 2024 8.48am; QSA, Research Guide to Immigration Records at Queensland State Archives, Assisted Immigration before 1901, page one.

[2] Ancestry.com. New South Wales, Australia, Assisted Immigrant Passenger Lists, 1828-1896 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

[3] See also https://www.nla.gov.au/research-guides/australian-shipping-and-passenger-records/queensland for all immigration lists available.

The original lists, however, present some problems.

Problems

- If the internet is slow or computers are old, it may be difficult to locate the original records on computer.

- Researchers of these lists need to be proficient at using computers.

- People in remote areas may not have full access to internet or computers.

- The original manuscripts are written in English Roundhand script (commonly known as ‘joined’ writing), a form of handwriting that is indecipherable to many younger researchers and academics.

- The writing itself may be difficult to decipher.

- There are many abbreviations used, and even if writing can be read, some of the abbreviations are difficult to understand.

- Often more than one list needs to be consulted and compared with other records.

- Names and ages on the original may be inaccurate. The information is only as good as the person supplying it, or the clerk who is writing it down.

- Differences in dialects even among English speakers, means that errors can easily occur.

Inaccuracies

A preliminary and cursive glance at the Artemisia’s original records illustrates inconsistencies and inaccuracies. Some can be verified within the easily available public record. For example, Bedworth, Warwickshire, England is wrongly recorded as Bulworth, Cornwall, and Pannal, a village near Harrogate in North Yorkshire, is recorded as Parnel.

The name of Ann Crabtree, a 19-year-old nurse, is entered in both the ‘single females’ and under ‘families’ on the indexes. Her birthplace is given variously as Dusebury or T’bury. Her official records reveal she was baptized on 17 May 1829 at All Saints, Dewsbury, Yorkshire. Another young lady Amy College (clearly spelt Colledge on one Shipping List) aged 14 years, and a single female, is the daughter of George and Elizabeth whose name was spelt as Collidge, and who were on board the vessel along with their daughter.

The spelling and confusion of names could be explained through clerks (sometimes semi-literate), trying to decipher the different dialects and accents, and then write names down. These accents were difficult to understand even for people travelling together. For example, Robert Inglis, a passenger on board, wrote that when a scuffle took place at the cooking galley ‘a sort of panic [was] created among the Emigts [emigrants] by one or two women screaming out in a loud Provincial dialect “a fighting” which sounded like the appalling cry of “a fire”. Everyone seemed pleased that it was only a row between the cook and the coffee roaster’.[1]

Robert Inglis, himself a literate man, is a prime example of a mismatch of detail within lists and indexes and a reminder to check and correlate even the original sources. Inglis was born on 4 January 1805 at Shotts, Cambusnethan, Lanarkshire, Scotland. The 1841 Census of Scotland records a Robert Ingles (rather than Inglis) aged 36.

His departure from England is sometimes given as Plymouth but this information is inaccurate because in his journal he writes that the family stayed at Deptford Depot before embarking from London. He also writes that they initially travelled from Scotland to London before arriving at Deptford Depot. His arrival at Moreton Bay is variously given as 6 December (the Artemisia was in Sydney on this date), and 16 December 1848. Still more anomalies abound. His daughter Margaret is recorded on one index as being born in Palia, Victoria (Australia) but, according to her birth certificate she was born in 1859 at Ballarat East, Victoria, registration number #7430 Victorian Registry of Birth, Deaths & Marriages. All these anomalies and more within the one family of Inglis/Ingles/Inglas!

The comments above are in no way a criticism of the records or previous histories. The official written record is quite often notoriously difficult to decipher.

[1] Journal of Robert Inglis-M1241-Box 3820-Queensland State Library, Oxley Manuscript Section.

The Passengers

This project aims to craft an inclusive narrative and to provide new interpretations where the workers and tradesmen, women, and children, of the Artemisia are visible and audible, providing (where possible) personal historical perspectives, experiences, and life stories.[1]

An e-publication The Artemisia: First Free Government Assisted Immigrants to Moreton Bay is forthcoming. Section One is set out in explanatory chapters. Section Two includes the biographies of passengers. Chapter one comments on how inconceivably wild this immigration scheme was and examines previous literature. Chapter two describes the preparations for passengers boarding the vessel; sightseeing in London, the Deptford Depot waiting to board the vessel, sailing down the channel, picking up passengers at Plymouth, and then sailing out to the open ocean. Chapter three describes the Artemisia and her first Captain, John Prest Ridley, the nephew of her owner Anthony Ridley. Chapter four describes the voyage. By consulting diaries and journals this chapter relates events and happenings on board during the months at sea. These are not necessarily known from other sources. Chapter five highlights the arrival of the Artemisia in Moreton Bay between 13-16 December 1848.

There are obvious anomalies within the numbers of passengers that disembarked in Australia, but this could be reflected and explained by the three who died during the voyage, (one being an adult, a Mrs Faulkner who died of stomach cancer, and who was buried at sea) and the four births during the voyage. Some of the crew also remained in Australia. James Greenfield, and John Loudon, both seamen, were charged with assaulting Robert Scott, one of the passengers, and spent a couple of months in Sydney goal. William Nichols, another sailor, absconded. [MBC 3 March 1849] The Captain, John Prest Ridley, later married and settled down in Sydney. His first child, a daughter was named Artemisia.

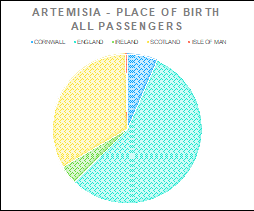

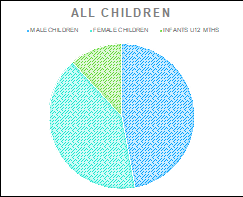

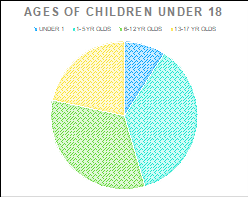

The passengers came largely from England and Scotland so that places of birth include England, Scotland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. Numerically there were about the same number of single males and families, although the numbers of persons within the category families was obviously much higher. There were around 20 single females on board. The mix of children was varied, with relatively the same gender balance overall, while 1–12-year-olds, as expected, were the highest proportion by age group.

These charts show the ages of children male, female and infants; and ages of children under 18 years.

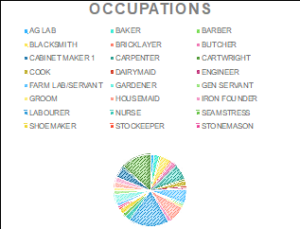

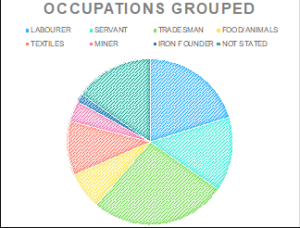

OCCUPATIONS OF PASSENGERS

One hundred and eleven passengers were recorded as having an occupation. The rest were described as ‘children’ or ‘wives’. Occupations were noted for adults, as young as 13 years to 17 years. The occupations of these young adults ranged from weaver, carpenter, shoemaker, and housemaid to seamstress. Between 18 to 21 years of age there were recorded 10 farm servants, 2 labourers, 1 agricultural labourer, 1 groom, 2 house maids, 1 weaver, 1 blacksmith and 1 iron founder. The Factory Acts 1833 United Kingdom prohibited children under the age of nine from working, and this is reflected in the ages of those on board the Artemisia and laws that also applied to workers in Britain’s colonies.

Significantly, the overwhelming majority of the first free immigrants on the Artemisia were either tradesmen (such as bricklayers, carpenters, or blacksmiths) or servants and labourers (such as farm workers, house maids, shepherds, and general servants). Occupations of single women appear to be cooks, dairymaids, nurses, housemaids, or seamstress and weaver.

[1] “Of all the wild schemes, this seems to be the wildest”, Letter from Captain John Wickham to Francis Merewether, 22 January 1849.

Why Immigrate?

Author Samuel Sidney asked the questions in 1852 ‘Why emigrate?’ and ‘Who should emigrate?’[1] He then outlined occupations that were useful within the colonies and compared them to wages and life in England. He commented firstly about skilled mechanics. ‘If some freak or fancy’ he wrote, ‘induces one of the class to emigrate to a rising colonial town, he very soon finds that he has made a change very much for the worse, unless he has a large family to provide for. His extraordinary skill is unappreciated: in nine cases out of ten a clever, make-shift botcher can earn as much money as the finished London, Birmingham, or Glasgow workman. To succeed he must become a jack of several trades: the skilled coach spring maker must condescend to shoe horses sometimes or be idle.’ … Sidney writes of social class and social standing, of the ‘nobs who are for the most part awful snobs’ and the ‘bullock driving community’ who has ‘nothing in common’ with the skilled mechanics.

Author Samuel Sidney in his Three Colonies comments that by 1852 ‘the demand in skilled trades is very limited … some trades such as a blacksmith, wheelwright, or carpenter may advantageously set their sons, from seven years old and upwards, to look after a little stock or cultivate land’. Amongst the families that emigrated to Brisbane there were passengers with these occupations. Daniel Corkhill, like Thomas Amies, was a blacksmith. He married Charlotte Hardwidge (1833-1886) on 24 March 1851 in Brisbane and they produced three sons and a daughter. He purchased eight acres in Dalby by 15 September 1857 NSW, suburban allotment No 2 of Section no 23 so that he was doing relatively well until he died 27 March 1862 in Queensland aged only 35 years. James Foster, on the other hand, was a blacksmith unhappy with his workplace. He absconded from his hired service at Bell’s property at Jimbour. James was described as ‘low sized, fair complexion, hair light brown, from 18-20 years of age’. He was with William Nichols, a free seaman per ship Artemisia. A warrant had been issued for their arrest and the reward paid ‘to any person lodging them in a Lock-up’.[2]

The carpenters from the Artemisia included John Baillie and Daniel McNaught. Both did very well and succeeded in business. Both Baillie and McNaught were trained carpenters from the Glasgow area and were amongst the first wave of Scottish immigrants to Queensland. John Baillie was involved with many buildings. It is thought that as a local carpenter and storekeeper Baillie built the courthouse and St Augustine’s church at Leyburn and All Saints Church of England at Yandilla. Reportedly he ‘received assistance from station workers and from Aborigines living on Yandilla at the time’.[3] Daniel McNaught went to the goldfields and prospected after emigrating to Moreton Bay but returned to Brisbane in 1855. His sister had married John Petrie so that it may have been family or work that drew him back to his skilled occupation as carpenter. McNaught became manager and foreman of Petrie’s joinery works and, in this capacity, supervised many significant projects around Brisbane.

Author Samuel Sidney mentions sawyers, tailors, tanners and curriers, shoemakers, brickmakers, stonemasons, saddlers and harnessmakers, miners, governesses and children. There is no mention of weavers in his Three Colonies but there was a contingent of weavers on board the Artemisia from the Bedworth and Coventry areas near the mills in central England. In 1821 a quarter of Coventry’s population of 21,000 were weavers. By 1841 there were some 30,000 weavers in Coventry working on 3,500 plain and 2228 jacquard looms. Weaving was traditionally a cottage industry, but gradually, due to the Industrial Revolution, as steam power and mechanisation developed, factories and ‘topshops’ took over from individual concerns. The focus in this area in the first part of the 1800s became silk ribbon weaving and Stevengraphs (pictures and bookmarks woven from silk) particularly in the Bedworth district and some of the passengers on the Artemisia gave these as their usual occupations.

[1] Samuel Sidney, The Three Colonies of Australia, Ingram, Cooke & Co., 1852, pp. 222-223.

[2] The Moreton Bay Courier 3 March 1849, p. 1.

[3] https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/heritage-register/detail/?id=600722

Comments & Conclusions

A prosopological approach (the Greek word for ‘face’ (πρόσωπο) is included in this word) that I have used to research and examine biographical data, explores those ‘faces’ and voices of the first government assisted free immigrants who were significant in the settling and building of Queensland. This process highlights the diversity, but also the ingenuity, courage, skills, and perseverance of those passengers of the Artemisia who have previously largely been ignored, forgotten, or generally relegated to a lesser role.

This project has produced evidence that the overwhelming number of passengers on the Artemisia were tradesmen or working people. Diversity is shown in the number of single males and females as well as the numbers of families with small children, who were on board. It is also shown through the different occupations and ages of the passengers.

Most came from England or Scotland.

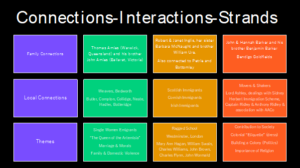

Connections Relationships and Strands

Relationships that abound on the Artemisia that are not easily evident can be traced through extended family history research.

James Butler, born in Bedworth, Warwickshire, England on 16 July 1818 to Thomas Butler (1796-1849) and Martha Brown (1793-1852) married Sarah College (variously spelt Colledge/Collidge) on 7 October 1838. They had children before and after the marriage. Jane Butler (also known as Jane Colledge/College) was their first child, born in 1836 at Bedworth Warwickshire. She sadly died in October 1868 at Foleshill, Warwickshire. Thomas Butler was born after their marriage on 31 July 1839 at Foleshill, Warwickshire. Thomas was baptised on 14 August 1839 at Bedworth but he died on the 30 September only a month after his birth. This tiny baby was buried on 2 October 1839 at Bedworth. Another son Joseph Butler arrived on 20 August 1840. By the time he was 10 months old the family were residing at “Roadisay” in the Parish of Bedworth. Sarah was then just 20 years old and had had one child out of wedlock (Jane who had died) and lost another small baby. She was soon to lose another child, Joseph, when he was one.

This couple was living near James Butler’s parents, Thomas, a coal miner aged 45 years and Martha, a ribbon weaver also aged 45 years. Joseph Butler aged 12 and Mary aged 9 were living with James’ parents and most likely were their youngest son and daughter, although it doesn’t state this on the census record. Many coal miners, ribbon weavers, and silk winders lived near them in the Parish of Bedworth, as well as two stone masons, a bricklayer, a couple of blacksmiths, a grocer, one washerwoman and one seamstress. There was a flow on from the Hugenout weavers in Bedford, from the town of Coventry nearby (famous for its Coventry lace and ribbon weaving). The district was one of tradesmen and women. It was a working class area.

The Butler family lived in Warwick, England in 1818; Bedworth, Warwick, England in 1841 according to the Census Records; and by 1848 they had emigrated with two small children to Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. By 1864 they were living at Maitland, New South Wales, Australia. James died on 26 September 1864 at Maitland West, and was buried at East Maitland on 28 September 1864.

Sarah Butler (Collidge/College) was baptised on 11 April 1819, at Bedworth, Warwick, England. She died one year after her husband James Butler on 19 December 1865 at Maitland NSW.

George Colledge 32, a miner, and Elizabeth 33 years, were also passengers on the Artemisia with their cousin, Amy Colledge, aged fourteen years who was recorded as a weaver.

George Colledge/Collidge and Sarah Butler (Colledge/Collidge) were siblings with common parents, William and Sarah Collidge. Brother and sister both emigrated in 1848 on the Artemisia.

The occupations of coal miners and factory workers, especially in and around Coventry and districts, are often seen in the British Census records in proximity. On the Artemisia this is reflected by the following locations and emigrants: Coventry near Bedworth – Mary Bottomly (Baker); from Poleshill near Bedworth – Mary Compton (nee Dunn); twenty-one-year-old Richard Botteridge was a weaver from Warwickshire. His parents were living at Warwick, Warwickshire, England; William Neale was an 18-year-old weaver both parents living at Warwick; and George Collidge (College/Colledge) was born in 1816 in Bedworth England. A miner/collier he married Elizabeth Hewitt on 25 December 1838 in the Parish Church at Bedworth, Warwickshire, England. Elizabeth Hewitt was born to parents Bethal Hewitt and Elizabeth Simmons in 1814 and baptised on 30 January 1814 at Bedworth, Warwickshire, England. A weaver, she married George Collidge on 25 December 1838 in Bedworth, Warwickshire. Elizabeth Collidge (Hewitt) died in 1879 in Queensland. During the Industrial Revolution with the introduction of steam powered machinery coal was needed to make the steam to run the machines and hence the proclivity of mining and weaving.[1]

The Amies and Collidge families and others like them, belonged to extended families and relatives who also emigrated, so that a pattern of chain migration can be discerned. Some passengers on the Artemisia indicated on the shipping lists that they had relatives in the colony before they emigrated and disembarked into Brisbane, Queensland (formerly Moreton Bay, New South Wales). Esther Aberdein had a brother and sister in Portland Bay (Victoria). Agnes Crawford had an uncle in Sydney, NSW. Alice Crawley from Armagh, Ireland had an aunt in Sydney, NSW. Edward Fisher, a farm servant, had a ‘father living in the colony’. Helen Kirk (McGregor) had an uncle in the colony. Robert Noble, a baker, from Beulah, Inverness had a brother at Wellington Valley. Thomas Peters, a 26-year-old labourer from St Germaine, Cornwall had an uncle living in Sydney. Thomas was a family man who had emigrated with his wife, Marian Peters (Dunbolt), and his two sons George Peters aged three and Henry Peters aged one year. Other passengers on board who had relatives in the colony included Muriel Rossiter (Fry) the wife of William Rossiter and mother of infant Henry Rossiter. She had a sister living in Sydney. Twenty-nine-year-old Margaret Wilson (Cameron) however had brothers and a brother-in-law in Sydney.

From this extensive list it can be clearly assumed that there were communications between families both in Australia and families back in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and “across the ditch” in New Zealand. Through journals and letters, diaries and life stories, the communications between family members and friends, the sharing of information and experiences between colonies of Australia and further afield, can be seen to continue well into the latter stages of the nineteenth century and beyond.

Thomas Amies was representative of this group. He had two older brothers James (1820-1840) and Jeremiah (1821-1856). A younger brother of Thomas, John Amies, born 1826, married Emma Walker/Williams/Amies/D’Arcy on 30 December 1851 at Stanton Lacy, Shropshire, England, after which they sailed to Point Henry (near Geelong) on the Success arriving on 31 May 1852.[2] Both John and Emma were described as Episcopalian and could both read and write. John was employed as a carpenter by John Highett of Barrabool Hills, Victoria, Australia. Emma Amies was employed too, as a servant.

After working for Highett for some time near Geelong this Amies family made their way to Ballarat, one of the richest gold diggings the world has ever known. Here they witnessed in December 1854 the uprising known as the Eureka Affair. John Amies and his family lived in a tent inside the rectangular compound known as the Eureka Stockade. Shots were fired at the tent when a candle was lit during a curfew so that sandbags were packed against the walls of the tent to protect their baby, Elizabeth Amies who wrote a journal in later life. Elizabeth’s father, John Amies, who was the brother of Thomas Amies (who was a passenger on the Artemisia), died in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia on 9 August 1858.

Linkages between seemingly unrelated surnames such as Petrie, McNaught, Ure and Inglis suggest strong familial ties and bonds between passengers. William Ure an 18-year-old iron founder is listed in the shipping under Single Males. He is the brother of Janet Inglis (Ure) and Barbara McNaught (Ure) who is the sister of Janet Inglis (Ure). Both Barbara and Janet and their families were passengers on board. Daniel McNaught was the husband of Barbara McNaught (Ure). His sister Jane Keith McNaught, a 22-year-old nurse, was also a passenger, and listed under Single Females. She was to marry John Petrie in Brisbane in 1850. There were distinct communications and assistance between families. This can be ascertained by following family members who were employed in family businesses. Sons, daughters, and other relatives can be found within names so that it can be assumed that those with strong familial ties were those that mostly continued well into future generations.

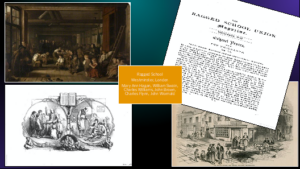

Although thousands of miles apart, new settlers experienced similar events, many not as vital or life threatening as being shot at during a civil insurrection, but others harrowing and dangerous, nonetheless. William James Swaine, for example, who was one of the single males from a Westminster Ragged School, who emigrated on the Artemisia as a 14-year-old shoemaker, told of an account in outback Queensland. He first took up work at Delgilbo Station on the Lower Burnett, when he landed in Moreton Bay, Australia, before carrying with a bullocky team between Ipswich, the Burnett and the Dawson. He married at Gayndah in 1857, then went to Cockatoo Station after which he became engaged by William Kelman of Ghingbindaa Station about 40 miles west of Taroom. Here his obituary states, ‘they had great experiences with the blacks [sic] fighting for the station, and their slab hut was fitted with portholes through which they had to shoot at the blacks. On several occasions Mrs Swain [sic], who was a native of West Meath, Ireland was the only white woman at that time on the station, and always carried a revolver for the protection of herself and her children during the absence of the men from the station’.

It is timely and fitting here to mention that the words used in earlier writings, letters, and even newspapers, are far from acceptable today, but they serve to illustrate the attitudes and experiences of early settlers, their actions and what was happening ‘on the ground’. I have transcribed Swaine’s obituary as it was reported, because to do otherwise lessens the impact of events. To transcribe (as written) provides differing interpretations and understandings, and, although only one side of the story it offers a completeness, that otherwise would not be forthcoming or felt.

The use of some vernacular of the past can be confronting and is certainly not in use in today’s cultural climate. The notion and scale of frontier violence in Queensland and elsewhere has often been “hidden” or unreported in past mainstream historical writings. Some excellent historians are only now beginning to address this issue of the whitewashing of many of the early eras in Australia’s history.

Many other avenues of research are offered from the research so far undertaken. Some suggestions include a closer examination of the Ragged Schools and immigrants from them to Australia.

Inter-colonial movements between Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia should prove an interesting study. Perhaps ventures to New Zealand and overseas, even those who returned to their homelands could be followed up in more detail. There are other “hidden” histories within each passenger’s family that could be brought to the fore.

By looking at how the earliest immigrants interacted with First Nations people and by seeking out contact stories, a fuller understanding of the impact of immigration could result in a shifting of the historical lens, by questioning stereotypes and generalisations.

The treatment of women, the reportage of family violence, the stories of children, the poor, or the mentally deranged, also have the propensity to provide a richer fuller history of the past. Too often these groups of people and themes have been ‘swept under the carpet’ in many mainstream historical accounts. The agency and courage of many European women has been clearly shown in some of the newer current histories, through a few contemporary accounts, that serve to explore and expand historical knowledge and the diversity of individuals and families.

I hope that in some way I have contributed to a broader knowledge of a little known facet of the free settlement in early Queensland.

View my short video here.

[1] Clancy Family Tree, Ancestry.com

[2] Dorothy Wickham, Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854, BHS Publishing 2009; Eurekapedia Wiki See: http://eurekapedia.org/John_Amies

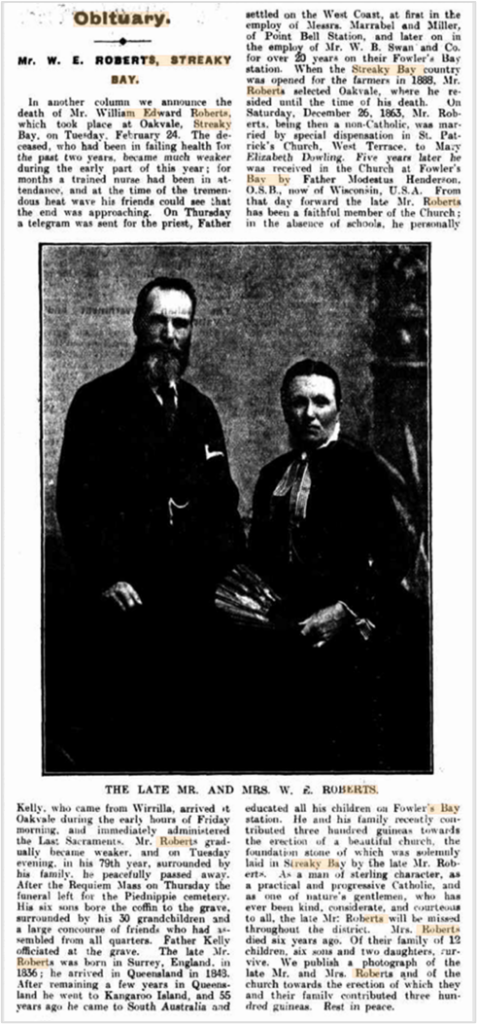

William Edward Shearing

The case study of William Edward Shearing Roberts clearly illustrates the value of checking all original records, and also, to compare them, as much as possible, in correlating and consolidating evidence.

William Edward Shearing was born in London, England. William who was an orphan was one of the boys from the Ragged School in London who sailed to Moreton Bay on the Artemisia. His mother, father & grandparents dead, he was travelling alone, his age given as 14 years, which I found inaccurate. After my research in finding his birth registration and biographical details I discovered this boy was 12 years of age. After reaching Brisbane William ‘spent the first five years of his colonial life on large sheep stations. During this time he was successively engaged in shepherding, hut-building, shearing, fencing etc.’[1]

Transcription: Shearing William Edward, 14 years, Carpenter, Lambeth Surrey, Parents: Edward & Elizabeth both dead, Church of England.

William Edward Shearing has been variously transcribed as William Edmund and Edmerston Shearing.

He died on 24 February 1914, aged 78 years, under the name William Edward Shearing ROBERTS in Oakvale, Streaky Bay, South Australia.[1]

He was born on 17 February 1836 so that the age of 14 years on the shipping lists is inaccurate.[2]

William Edward Shearing, a young lad from the Ragged School in London, was orphaned. His mother, father & grandparents dead, he was travelling alone on the Artemisia. After reaching Brisbane, at 12 years of age, he ‘spent the first five years of his colonial life on large sheep stations. During this time he was successively engaged in shepherding, hut-building, shearing, fencing etc.’[3]

Baptisms, St Mary, Lambeth, Surrey, 1836

13 March, No. 1962 William Edward son of

Edward & Elizabeth SHEARING; Abode: Regent St; Trade: Coach spring maker

Note: Parent’s names and place of birth match shipping record.

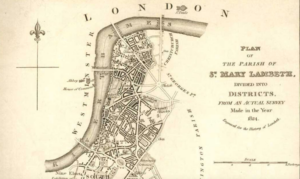

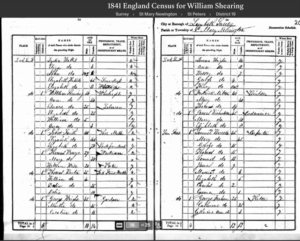

In 1841 five-year-old William Edward Shearing was living in Lambeth, London, with his extended family: grandparents William and Ann Shearing; parents Edward John Shearing and Elizabeth Shearing (nee Brown); and his sister Ann Shearing who was three years of age. His parents had married on 28 December 1834 at St Mary’s located near Lambeth Palace.[4] The family had a long association in the Parish and can be traced back in Lambeth, Westminster, and St Martin in the Fields to the 1600s.

Tragedy befell William. His father died in September 1841.[5] His grandmother died in 1846 and his grandfather in 1848. His sister was described as a pauper and in the workhouse. His mother died some time before he emigrated.

Engraving published by J. Allen, Princes Road, Kennington. University of Greenwich,

https://ideal-homes.gre.ac.uk/lambeth/lambeth-assets/maps/lb-of-lambeth/st-marys.html.

Surrey, St Mary Newington,

St Peters, District 19

City or Borough of Lambeth, Surrey

Parish of St Mary Newington

Little Sun Street

William Shearing, 50, Wheelright

Ann Shearing, 50

Edward Shearing, 25, labourer

Elizabeth Shearing, 25

William Shearing, 5

Ann Shearing, 3

William was an orphan, in the Ragged School at Westminster. Lord Shaftsbury who founded the school, imagined it would be a good idea to send around eight of the boys and girls from the Ragged School on the Artemisia as free immigrants to Moreton Bay. A 12-year-old boy, William Edward Shearing was literate and could both read and write. He had no relatives in the colony. His state of bodily health was good, and he had no complaints regarding his treatment on board.

When he disembarked he was employed as a jackaroo on stations in Queensland for around five years. ‘During this period he was successively engaged in shepherding hut-building, shearing, fencing etc., and the life proved a very hard one, owing principally to the treacherous nature of the blacks who were very wild at that time. The sheep had to be guarded both day and night, to prevent ravages, and despite every care it was no unusual thing for the men so engaged to be robbed of all rations and to only narrowly escape death from the spears and boomerangs of the natives. … In 1854 he and his mate left Queensland, setting out overland for Adelaide on foot. Striking the river, they made bark canoes and paddled down the stream, ultimately reaching their goal. Soon after William Edward Roberts ‘went to Kangaroo Island’ and around 1859 ‘he came to South Australia and settled in the West Coast’.[6]

Between 1854 and 1863 William undertook droving between Port Lincoln and Fowler’s Bay. Mary Elizabeth Dowling and William Roberts (Shearing) were married on 26 December 1863 at St Patrick’s Church, Adelaide. It has been suggested by family members that William took on the name Roberts soon after he arrived in Queensland. It is not known why he did this. William and Mary had ten children in 21 years and became pillars of society in Streaky Bay. They were lauded as a Great West Coast Catholic Family.[7]

The Southern Cross (Adelaide), 13 March 1914, p. 12

William died on 24 February 1914 at Oakvale, Streaky Bay and was buried at Piednippie Cemetery with his wife Mary Elizabeth Roberts (nee Dowling).

[1] The Southern Cross, Adelaide, 13 March 1914, p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.govve.au/nla.news-article167792369. The obituary states he emigrated on the Artemiscia [sic] in 1848.

[2] London Metropolitan Archives; “London, England, UK”; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P85/Mry1/359, Baptisms, St Mary, Lambeth, Surrey, 1836 13 March, No. 1962 William Edward son of Edward & Elizabeth SHEARING; Abode: Regent St; Trade: Coach spring maker; FHL Film Number 0254608-0254612; FHL Film Number 1041529 Reference ID #246 (page 246).

[3] The Southern Cross, Adelaide, 13 March 1914, p. 12.

[4] Select Marriages, 1538-1973, FHL Film Number 1041644, Reference ID Item 3, p. 63.

[5] Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915, July-Aug-Sep, Newington, London, UK, Volume 4, Page 229.

[6] The Southern Cross (Adelaide), 13 March 1914, p. 12.

[7] The Southern Cross (Adelaide), 12 July 1912, p. 6.

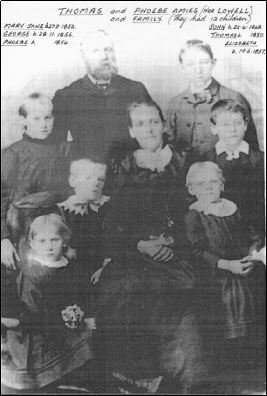

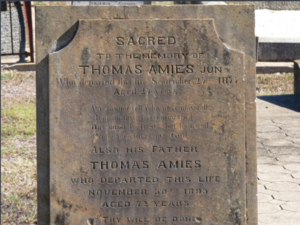

Amies Family

Blacksmith Thomas Amies came to Queensland with his wife and small child. His contribution to civic life and his story is uplifting and is indicative of many new free settlers. The Amies and their three-month-old baby John Amies, embarked from Plymouth arriving in Moreton Bay in mid-December 1848. The family moved from Brisbane to Warwick, Queensland in 1849 establishing a farrier business. They were amongst the earliest settlers in the district.

Warwick District & Pioneers, p. 9

When Queensland’s First Governor paid his first official visit to Warwick in 1860, instead of a gun salute to welcome the Governor, Messrs Amies and Craig ‘who had charge of all arrangements in connection with the salute, had organised an anvil battery in lieu of cannons. The anvils were all charged with gunpowder, the wads being pegs of wood driven home by sledgehammers and weighed down by heavy weights. As the imposing cavalcade came into the town the salute was fired in perfect time, with excellent effect, amidst the wildest excitement’.[1]

Thomas Isaac Amies was born to John Amies (1795-1869), a wheelwright, and Mary Ann Amies/CHILDS (1797-1857) on 12 March 1824 at Ditton Priors, Shropshire Unitary Authority, Shropshire, England.[2] They had been married on 26 July 1817.

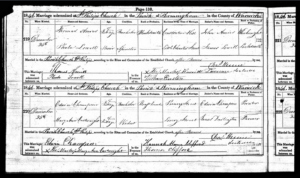

Their son, Thomas Amies, married Phoebe Lowell on 25 December 1846 at St Phillip’s Church in the Parish of Birmingham, Warwickshire. He was then described as a blacksmith living at Constitution Hill while Phoebe was described as a spinster and of ‘minor’ age, living at Little Charles Street. Her father James Lowell was described as a locksmith.

Thomas Amies was involved in the first Wesleyan Church in Warwick and one of those who distributed tickets for the Public Tea and Meeting in 1858.[3]

The following appeared in the Moreton Bay Courier, 28 August 1858:

OPENING OF THE

NEW WESLEYAN CHAPEL,

WARWICK DARLING DOWNS.

THE above will he OPENED for Divine Service on SUNDAY, September 5.

The Rev. SAMUEL WILKINSON, of Brisbane, will Preach in the morning at 11, and in the evening at 7.

Collections will be made.

On MONDAY, 6th, (following), a PUBLIC TEA and MEETING will be held, when statements of expenditure will be given, and Addresses delivered by several Ministers and gentlemen. Tea at 5-30 p.m. ; Chair to be taken at 7.

Tickets 2s. 6d. each, to be had of Messrs Jonathan Harris, Geo. Walker, Thomas Amies.

The proceeds applied to the Building Fund.

N.B.-On the afternoon of Sunday, the 5th, at 3, an Address will be delivered to the Children of the Sabbath School, their parents, and friends, by the Reverend WILLIAM FIDLER, at which there will be no collection.

Children of Thomas and Phoebe Amies (Lowell)

- John (23 April 1848 Birmingham, England – 10 Feb 1920 Queensland)

- Thomas Lowell (24 Feb 1850 Qld – 27 Sep 1877 Qld)

- Mary (27 Feb 1852 Qld -1930 Glenn Innes, NSW)

- Phoebe (4 Jan 1854 Qld – 10 Oct 1927 Qld)

- George (29 Nov 1855 Qld – 4 Aug 1923 Warwick, Qld)

- Elizabeth (3 Mar 1857 Warwick, Qld – 29 Oct 1920 Gunnedah, NSW)

- James (15 Sep 1858- 8 Jan 1860)

- Samuel (5 Aug 1860 Qld – 2 May 1923 Qld)

- Hannah (27 Aug 1862 Warwick, Qld – 4 June 1947 Brisbane, Qld)

- Angelina (24 June 1864 Warwick, Qld -12 June 1944 NSW)

- Isabella Amies (21 June 1866 Warwick, Qld – 28 Mar 1925 Brisbane)

- Ann Amies (29 Mar 1870 Warwick, Qld – 28 Sep1957 Glen Innes, NSW)

- Eva Amies (16 June 1871 Warwick, Qld – 1951 Queensland)

Children of Thomas and Phoebe Amies (Lowell)

- John Amies (23 April 1848 Birmingham, England -10 Feb 1920 Qld)

John was baptised on 3 July 1848 at St Phillip’s CE, Birmingham, Warwickshire, England. He emigrated on the Artemisia with his parents leaving England in July when he was only three months old, arriving in Moreton Bay in December 1848. He married Bridget McAllister on 26 September 1877 in Maryborough, Queensland. [•Marriage registration. Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, 1877/C/691.]

2. Thomas Lowell Amies (24 Feb 1850 Queensland – 27 Sep 1877, Warwick, Qld)

Thomas married Isabella McNevin in Brisbane, Qld on 7 June 1876. Their daughter Beatrice Amies was born 3 March 1877. It was a difficult couple of years for Isabella. Thomas died six months after their first child was born, and then Beatrice died on 9 April 1878 aged only 12 months old. [Marriage Registration. Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, 1876/C/56.]

- Mary Amies (27 Feb 1852 Qld -1930 Glenn Innes, NSW)

Mary married Robert Wood in Warwick, Qld on 11 July 1867, aged 15 years. They produced Charles Ernest Wood (1888-1963) and Arthur Lowell Wood (1891-1949).

- Phoebe Amies (4 Jan 1854 Qld – 10 Oct 1927 Qld)

Phoebe married John Gale in Warwick, Qld, on 3 Feb 1880. They produced John Gale (1881-1881); Samuel Gale (1882-1882); Arthur Gale (1883-1958); Herbert Gale (1885-1950); Marcus Gale (1887-1956); Clara Gale (1889-1974); John Gale (1891-1892); Frederick Thomas Gale (1896-1961).

- George (29 Nov 1855 Qld – 4 Aug 1923 Warwick, Qld)

He married Margaret Newcombe in Warwick Qld on 11 Dec 1895, and they produced Violet (1895-1896); Thomas Amies (1897-1973); Florence Amies (1899-1975); Phillis Amies (1902-1985); Roy Amies (1905-1985); Elsie Amies (1911-1963).

- Elizabeth (3 Mar 1857 Warwick, Qld – 29 Oct 1920 Gunnedah, NSW) Elizabeth married John Thomas French in Warwick, Qld on 1 Jan 1878. They produced Lilly May French 23 Oct 1878 [1878/C/5536] ; Ethel Maud French 10 May (1880-1968) [1880/C/4358]; Amy May French (20 Dec 1881-1961) [1882/C/4337]; Norma Lily French(1883-1963) [1883/C/5330]; Ivy Violet (30 Sep 1885-) [1885/C/9027]; Florence Muriel French (1887-) [1887/C/1503]-; Millicent Mabel French (11 April 1889-1969) [1889/C/1895].

Elizabeth died on 29 October 1920 at Gunnedah, New South Wales.

7.James (15 Sep 1858 Qld – 8 Jan 1860 Qld)

- Samuel (5 Aug 1860 Qld – 2 May 1923 Qld)

Samuel married Elizabeth Dauth on 17 April 1891 in Queensland.

- Hannah (27 Aug 1862 Warwick, Qld – 4 June 1947 Brisbane, Qld) Hannah married George Boddington at Warwick, Qld on 27 August 1884.

- Angelina (24 June 1864 Warwick, Qld -12 June 1944 NSW)

She married James Arthur Bracey who died in 1937, predeceasing her. They married in Warwick, Qld on 12 January 1898. They produced Uma Amies Bracey (1898-1965) and Gladys N Bracey (1900-).

- Isabella Amies (21 June 1866 Warwick, Qld – 28 Mar 1925 Brisbane)

Isabella married Frederick Blackwell on 15 October 1888 in Queensland. They produced Lavinia Isabel Blackwell (1889-1976); Ivy Clarinda Blackwell (1890-1891); Elsie Lillian Blackwell (1891-2001); Edna Pearl Blackwell (1894-1900); Lowell Keith Blackwell (1899-1900); and Hadley Frederick George Blackwell (1903-2001).

- Ann Amies (29 Mar 1870 Warwick, Qld – 28 Sep1957 Glen Innes, NSW)

Ann married Daniel Nevill in Queensland on 3 Sep 1890. They produced Olive Clarinda Nevill (1891-1891) and Roland William Nevill (1892 -).

- Eva Amies (16 June 1871 Warwick, Qld – 1951 Queensland)

Eva married Thomas Wilson and they produced a son, Thomas Wilson.

Brother of Thomas Amies

John Amies was the brother of Thomas. John married Emma Williams in Shropshire so it can be assumed they both arrived at Port Henry, Victoria, together and went to the goldfields of Ballarat sometime before June 1853 because that is when their first child, Elizabeth Anne Amies was born, on the Eureka Lead, Ballarat East, near the site of Eureka Stockade. John Amies was a carpenter. With his wife Emma Amies (Williams) he lived in a tent inside the Eureka Stockade. Shots were fired at the tent when a candle was lit during a curfew. Sandbags were packed against the walls of the tent to protect their baby, Elizabeth Amies. John died of tuberculosis on the 7 August 1858, after contracting it two years earlier. Prior to his death he was a hotelier. After John died Emma remarried. They were both buried in Ballarat.

[https://www.eurekapedia.org/John_Amies

Notes Peter Berlyn

Dorothy Wickham, Women of the Diggings: Ballarat 1854, BHS Publishing, 2009.

Obituary of Thomas Amies

Thomas Amies in his obituary was described as a ‘familiar figure’ in the streets and ‘a man of the kindliest nature’, ‘a tradesman who took a pride in his work’, a ‘generous friend and loyal citizen’ who ‘earned the esteem of all with whom he came in contact’ with. Thomas was active in municipal matters and saw the rise and progress of Warwick. Until a month or two before his death in his 73rd year he worked hard. He died from complications and heart trouble on 30 November 1895, at Warwick, Southern Downs Region, Queensland, Australia.[4]

[1] Warwick District and Pioneers, p. 93

[2] Pallot’s marriage index, 1780-1837

[3] Moreton Bay Courier, 28 August 1858, p. 3

[4] Warwick Argus, 3 December 1895.