THIS PROJECT PRESENTS FRONTIER CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EASTERN QUEENSLAND BETWEEN THE 1820S AND 1850S.

This website has been developed from the research findings of Dr. Ray Kerkhove. It was built with a team of IT Masters students from Griffith University: Austin Odigie, Nkem Awujo, Hamed Bakhtiari and Saman Kayhanian. Revised in 2017 by Sumal Ranasinghe, Pathum Sameera, Amila Perera & Shoan Jacob a group of IT Bachelor Students of Griffith University.

Dr Kerkhove was a visiting Fellow from 2016 to 2017 at Griffith’s Harry Gentle Resource Centre, a digital portal of resources concerning the pre-Separation (pre-1859) history of Queensland. Ray’s speciality is the Aboriginal history and Aboriginal material culture of southern Queensland during the earliest decades of contact (1820s-1870s). He has written and presented various public and conference talks, articles, reports and books in this field, often working with Aboriginal families on reviving and reconstructing specific aspects of their lives. A major interest of his has been creating overviews of the historical landscapes that would better illustrate Indigenous presence and provide a more inclusive overview of the conflicts and lifestyles of those times.

The project visually presents the resistance wars in south-eastern Queensland in an easily-digestible and informative manner, by combining maps, images and brief explanations. Dr Kerkhove seeks to better illustrate the typical lifestyle of settlers and Aborigines caught in the resistance wars. He also seeks to develop historical maps that better reflect what was happening from an ‘Aboriginal resistance’ perspective.

Dr. Ray Kerkhove’s book Aboriginal Camp Sites of Greater Brisbane is described as the starting point to finding campsite locations in the Brisbane region.

Kerkhove, R. (2015), Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane: An Historical Guide, Salisbury: Boolarong.

Pastoral Settlement as Invasion

Invasion by Default

Frontier conflict was, for the most part, invasion by default. Settlers took up land already occupied by Aboriginal people and were supposed to make some allowance for Indigenous use of those areas, but few had any idea of how to come to mutually satisfactory arrangements for their intrusion.

European landholdings cost Aboriginal groups dearly. Thus the settlers’ presence was rarely welcome. Very often, European modes of land use resulted in devastating loss of Aboriginal food resources, pollution and degradation of water sources and grasslands, reduced access to important areas, and vandalism of sacred sites and burial grounds.

Only some settlers were aware of this. Fear, ignorance of Aboriginal culture and lifestyles, or the struggle of trying to grow crops or run livestock in ‘wild’ country worked against the pursuit of peaceful arrangements.

Pastoral settlement of south-east Queensland largely expanded from the northern rivers of NSW – from the McIntryre into the Darling Downs then down into the Lockyer or otherwise across the Scenic Rim. However, there was also a move up the Brisbane River and west of Ipswich.

Generally, newcomers arrived in groups of several or a dozen people with a dray (bullock wagon) of goods. They came mustering a herd or flock of hundreds to thousands of sheep or cattle. At a suitable location by permanent freshwater, the settlers would establish their headquarters (a hut, tent or upturned dray) and build a pen – up to an acre in size – to keep their livestock at night. The areas they occupied were at least 10 square kilometers each. These were called “runs” as the settlers freely ‘ran’ livestock across the entire unfenced area.

Communication with other settlers relied on continued traffic of drays coming and going with supplies and produce. For this reason, dray routes and dray camps were important. Most settlers established themselves roughly 10 miles apart so that they could – if needed – visit each other.

Usually the owner of the land did not live on the run but appointed an overseer who resided at the head station (a set of huts). As livestock had to be rotated around the area for grazing, most runs had a few ‘outstations.’ These consisted of a livestock pen and a couple of huts, manned by one to three shepherds or stockmen.

Settlers’ Defenses

For the most part, settlers relied on their own resources to defend the runs they established. Most of the fighting in resistance wars was conducted by groups of squatters – near-neighbours – and the servants or workers of these runs. They would form parties of 10 to 40. Most persons living on the frontier were heavily armed and some also had supplies and ‘safes’ of gunpowder, guns and rifles. Muskets were the main weapon until replaced by carbines. Many settlers also used attack dogs.

On the edge of the frontier, many huts were built with hatches rather than windows to enable the whole building to be shut tight. Some huts had loopholes for shooting and peepholes for surveillance. For further defense, areas around homes were often broadly cleared, and the hut was built at a vantage point with a ring fence. Some early huts also had watchtowers and warning (bell) towers.However, most fighting occurred at or near outstations. Thus the humble sentry box of the night watchman was often the scene of conflict.

Policing, Military and Para-Military Bodies

It was largely between 1823 and 1849 that armed forces were used against Aboriginal fighters in Queensland. There was only a very small number of soldiers available. Being largely foot soldiers, they were mainly used for psychological effect, though there were several military expeditions, and soldiers were utilised in combination with other forces. Mounted (border) police, under the control of Lands Commissioners (Simpson, Rolleston) were similarly few in number – from 6 to 12 usually – and were spread very thinly across the region. Like the soldiers, their main purpose was to give squatters and their families a sense of security, or otherwise extra fire power when needed.The Native Police corps was a para-military body established in 1848. It consisted of native (Aboriginal) troopers under white officers. Initially these forces were small (again roughly a dozen men) but by the 1850s-1860s they were the main force dealing with Aboriginal resistance and numbered 150-200.Town police did not have their own horses and only operated inside towns but were sometimes employed to cajole Aborigines to leave the town precincts, or to arrest Aborigines within town confines.

Settler Tactics

Some settlers used horsemen and herds to intimidate and drive off Aboriginal groups, or engaged in pre-emptive strikes against Aboriginal camps. Boundary riders – staff on horseback – regularly patrolled each run to check on the welfare of the herd. In many cases they also dispersed or attacked any Aborigines they saw troubling the herds.

Often, when an Aboriginal group killed a white man or inflicted a great deal of damage on herds or crops, certain settlers would send messages around the adjoining runs and form a punitive expedition. If the threat was serious enough, or they were unable to make sufficient progress, they would also call in police and soldiers.

The most common action by squatters was the preemptive or punitive ‘dawn raid’ on a camp – an ambush that escalated into a battle as the camp occupants fought back.

These raids might be simply a display of gunfire and horse skills aimed to terrify the occupants, or targeted to arrest a particular individual, but they could include the massacre of all residents. Surprise attacks (dispersals) of large Aboriginal gatherings served a similar purpose. Pitched battles between punitive parties and Aboriginal warriors were rarer but did occur.

References

Books

Bartley, N. (1896), Australian Pioneers & Reminiscences, Brisbane: Gordon & Gotch.

Bottoms, T. (2013), Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times, London: Allen & Unwin.

Dutton, G. (1985) The Squatters, Ringwood: Viking O’Neal.

Fisher, R., ‘The Brisbane Scene in 1842,’ in Rod Fisher & Jennifer Harrison, (2000), Brisbane: Squatters, Settlers and Surveyors, Brisbane History Group Papers No 16, Brisbane.

Gray, W. J. B. (1902), ‘The Early Days – Pioneers and Droving on the Darling Downs’, Frank Uhr Archives.

Grey, J. A. (1999),‘The Military and the Frontier, 1788-1901,’ in Jeffery Grey, A Military History of Australia, New York: Cambridge University.

Hodgson, C. P. (1846), Reminiscences of Australia with Hints of the Squatters Life, London: W N Wright.

Lergessner, J.G. (2007), Death Pudding: The Kilcoy Massacre, Kippa Ring: James Lergessner.

Orsted-Jensen, R. (2011), Frontier History Revisited – Colonial Queensland and the ‘History War’, Lux Mundi: Brisbane.

Richards, J. (2008), The Secret War: A True History of Queensland’s Native Police, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Journals

French, M. (1989), ‘Conflict on the Condamine: Aborigines and the European Invasion: a history of the Darling Downs’, Frontier, Vol. 1, Toowoomba: Darling Downs Institute.

MacKenzie-Smith, J. (August 2009), ‘The Kilcoy Massacre’, Queensland Historical Journal, Vol. 20:11, pp. 593-605.

Images

Settler’s camp, Warra, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg. No. 187400.

Gwambegwine Station Property, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image No: APO-026-0001-0021.

Sidney, S. (1853), The Three Colonies of Australia: New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia; Their Pastures, Copper Mines, & Gold Fields, 2nd edition, Project Gutenberg Australia eBook.

Rifle – Cavalry Carbine, Lacy & Co, London, 1850s, Museums Victoria Collections.

Sentry box at an outstation, Stieglitz, Emma von & Von Stieglitz, K.R. von, (1964), (Hobart).

Sentry on alert at a sentry box, Item 02: Sketchbook of Andrew Bonar [1854, ca. 1857-1860, 1913], State Library of New South Wales, Call No. PXA538/vol.2.

Main uniform of 1840s soldiers (The British Army in Australia 1788-1870 [cd-rom] : index of personnel / James Hugh Donohoe).

Uniform of town policeman, Archaeology on the Frontier, The Men in Blue (and Red): A Brief History of the Qld NMP uniform.

Native Police Corp, Australian Native Police, Wikipedia.

Stockman, Australian sketchbook: Colonial life and the art of St Gill, State Library of Victoria. .

Boundary riders, George Hamilton, Overlanders attacking the natives 1846, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Wikimedia.

Rufus River, William Anderson Cawthorne, Drawings of Australian Aborigines and objects of material culture, ca. 1844-1864, State Library of NSW, Call No. PXD70.

1850s illustration of a night attack, Cooper, F., (1857), Wild Adventures in Australia and New South Wales: Beyond the Boundaries, London: Blackwood.

Illustration titled ‘The Avengers’, Wilson, E., (1859), Rambles at the Antipodes: A series of sketches of Moreton Bay, New Zealand, the Murray River and south Australia, and the overland route, London: Smith & Son.

Hideouts and Bastions of Resistance

The Power of ‘Bastions’

Settlers’ accounts refer to specific sites within south-east Queensland as hotspots from which Aboriginal resistance tended to repeatedly emerge. These were areas where the natural environment made camps difficult to access. Most had sufficient resources to enable groups and raiding parties to survive. These sites had secluded camps, and in some cases, stockpiles of weapons and even ‘bush pens’ for keeping stolen sheep and cattle. Here resistance leaders such as Dundalli, Yilbung and Multuggerah are reported to have retreated when pursued.

The Geography of Hideouts

Hideouts were mostly large islands, rocky/hilly regions, swampy areas or dense forests (“scrubs”). Their geography frustrated or at times completely halted pursuers – especially Europeans on horseback. Partly for this reason, there were concerted efforts by settlers to clear dense woods, especially near areas of settlement.

Inter-Tribal Gathering Venues and Inter-Tribal Planning

The most useful hideouts were places that that were already a venue for inter-tribal meetings. Such sites enabled attendees to plot combined or simultaneous attacks. For example, the triennial Bunya Festival (Blackall & Bunya Ranges) drew groups from all over southern Queensland and northern NSW. It was reported that major offensives were often launched after meetings here. Various European observers (e.g. James Bracewell) testified that much of the discussions at such meetings concerned such objectives. Bribie Island and Fraser Island and their adjoining coastlines (Toorbul/ Pine Rivers and Cooloola) had a similar role. These areas had traditionally seen inter-tribal gatherings and tournaments for the communal fishing of the winter mullet runs.

References

Archival

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Box 7072 Karl W E Schmidt (1843), Report of an Expedition to the Bunya Mountains in Search of a Suitable Site for a Mission Station, p.5, Acc 3522/71.

Books

Bloomfield, G. (1986), Baal Bellbora: The End of the Dancing Chippendale: APCOL.

Connors, L. (2015), Warrior: A Legendary Leader’s Dramatic Life and Violent Death on the Colonial Frontier Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Mark Copland, Jonathan Richards & Andrew Walker, (2010), One Hour More Daylight: A Historical Overview of Aboriginal Dispossession in Southern and Southwest Queensland, Toowoomba: Social Justice Committee.

Kerkhove, R. (2012), The Great Bunya Gathering – Early Accounts, Enoggera: Pemako.

Reynolds, H. (1982), The Other Side of the Frontier, Melbourne: Penguin.

Reynolds, H. (2013), Forgotten War, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, pp. 53-4.

Ryan, L. (1981), The Aboriginal Tasmanians, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Journals

Connor, J. (2004), ‘The Tasmanian Frontier and Military History’, Tasmanian Historical Studies, Vol. 9.

Connors, L. (2005), ‘Indigenous resistance and traditional leadership: understanding and interpreting Dundalli’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 19:3, pp. 701-712.

Dennis, P., Heffrey Grey, Ewan Morris, Robin Prior, John Connor, (1995) ‘Aboriginal Armed Resistance to White Invasion’, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, Melbourne: Oxford University.

Evans, R. (2002), ‘Against the Grain: Colonialism and the Demise of the Bunya Gatherings, 1839-1939’, Queensland Review No. 9:2, Nov 2002, 64.

Laurie, A., (1959), UQ Fryer MSS, ‘The Black War in Queensland’ in Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 6:1, pp. 155-173.

Ryan, L., (2013), ‘Untangling Aboriginal resistance and the settler punitive expedition: the Hawkesbury River frontier in New South Wales, 1794–1810’, Journal of Genocide Research, Vol. 15:2, pp. 219-232.

Conference papers and reports

Kerkhove, R, (2014), ‘A different mode of war? Aboriginal ‘guerilla tactics’ in defining the ‘Black War’ of Southern Queensland 1843-1855,’ A paper presented July 2014, AHA Conference, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Kerkhove, R., (2015), Report: Indigenous Use and Indigenous History of Rosewood Scrub, Brisbane: Jagera Daran.

Newspapers

‘Mackay’s Rural richness Began at Fort Cooper – Story of South Fort Cooper Station’, Daily Mercury (Mackay), 17 October 1945, p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article170627984.

Bennie, J.C. (1931), ‘The Bunya Mountains – Early Feasting Ground of the Blacks’, The Dalby Herald, 13 February 1931, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217542226.

Clark, W. (1912), ‘Explorer Walker – Organiser and First Commandant of the Native Police’, The Brisbane Courier, 28 December 1912, p. 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19830766.

Meston, A, (1923), ‘The Bunya Feast – Mobilan’s Former Glory. In the Wild, Romantic Days’, The Brisbane Courier, 6 October 1923, p. 18. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20633974.

Images

Snars, F., (1997), German Settlement in the Rosewood Scrub: A Pictorial History, Gatton: Rosewood Scrub Historical Society Inc., p. 11.

Mountford, C. P., Camel string with Aboriginal smoke signals in the background, near Uluru, Northern Territory, ca. 1940s, National Library of Australia. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-156262893.

Hillside view of Bunya Mountains ca. 1897, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg. No. 142329. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183509305902061.

Traditional Warfare and Alliances

Traditional Aboriginal Warfare

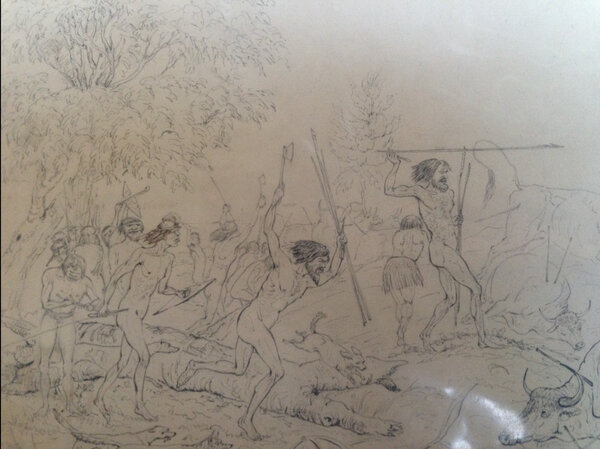

The most usual pattern of Aboriginal warfare was either a ‘payback’ punitive expedition targeting a specific individual, or otherwise a raid to steal (or bring back) particular women. For such excursions, a small party of usually 3-7 men made a secret journey deep into enemy territory, conducted their killing or raid in a surprise ambush, and swiftly returned. Sometimes the ‘avenging party’ was supported indirectly by a much larger body of warriors. Targeted killing of whites (e.g. outstation shepherds) seem to have evolved from this practice.

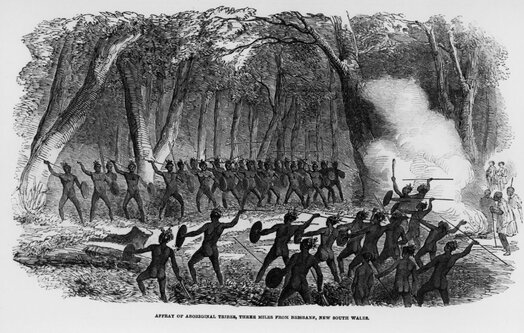

Less often but very spectacular were inter-tribal tournaments. These were highly formal arrangements involving several tribes – many hundreds to thousands of participants. Often the entire group would camp at designated places and the battles were held on an open flat between the camps. The cause was often a grievance over trespassing and infringement of hunting rights. Combatants would form lines, with novices being allowed to fight before the senior warriors, who would file out very formally as the fight livened up. These seasoned warriors (and champion warriors) eventually engaged in one-on-one fights with their opponents as the battle continued. At this point, women also engaged in one-on-one fights, usually with yam sticks.

A battle in such cases was ‘won’ by one of the parties drawing blood or otherwise by driving the opposition off the field and onto the ridges where the camps were. In most cases, if anyone was wounded or killed, the battle ended, although fighting might be re-started several times after each set of casualties were tended to. Overall, casualties were reportedly few and most of the ‘battle’ consisted of venting grievances, bluff and intimidation (displays of aggression) or skilfully dodging the spears and other weapons of the opponent. Pitched battles of warriors with settlers and police seem to have evolved from inter-tribal tournaments, but as these could result in tremendous loss of life for the Aboriginal participants due to the superior power of gunfire, they were resorted to rather intermittently – for example, if a large party or camp was directly attacked.

Traditional Weapons

The basic weapon of SE Queensland warriors was the spear. A warrior carried a number of these into a fight, and also relied on spears tossed by the enemy. Some spears were extremely long and strong, and could be hurled great distances.

Boomerangs and clubs were also used in fighting. Some clubs were fashioned to be thrown from a distance. Tomahawks and knives (originally of stone) were used in close-range fighting, though there are reports of tomahawks being thrown. In post-contact times, steel tomahawks obtained by trade, and knives fashioned from broken bottle glass or old shears were preferred. It also became common to attach horseshoe nails to the heads of clubs to improve their lethal capacity.

Tribal Alliances in resistance: the aftermath of the Kilcoy Massacre

In much of Australia, resistance occurred on a group-by-group basis, steadily moving across the continent. Nevertheless, early sources record warriors from one Aboriginal group at times combining with one or even a few other Aboriginal groups in a concerted effort.

Traditionally, many parts of Australia had groups that at times conducted ceremonies, tournaments, hunting drives and other activities together. Willie MacKenzie (a Kilcoy elder) recalled that the many groups of south-eastern Queensland formed five large tribal alliances, who came together especially during staged fights (inter-tribal tournaments), although their partnerships shifted from time to time. The alliances and their inter-tribal activities probably explain the reports of “hundreds of warriors” attacking runs.

As the feature map shows, the Kilcoy massacre of 1842 riveted many of the usually-feuding groups into combined actions against settlement. Based on reports from escaped convicts and missionaries, the Lands Commissioner Dr Simpson reported to the NSW Governor that some 14 tribal groups had together declared enmity against white settlement. It is not clear how long this combined effort continued. However, some (on Moreton Bay and south of Brisbane) had already had their battles during the 1830s and had reached agreements of some sort with the settlement. It also seems that different groups fell away from these combined efforts quite quickly on account of the horrific retaliation against their people.

References

Books

Hodgkinson, C. (1844), Australia from Port Macquarie to Moreton Bay with Description of the Natives, London: T & W Boone.

Petrie, C. C. (1904), Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland Brisbane, Watson, Ferguson & Co.

Journals

Darragh, Thomas A. & Fensham, R J. & Queensland Museum, issuing body. (2013). The Leichhardt diaries: early travels in Australia during 1842-1844. South Brisbane: Queensland Museum, p. 266. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/6453570.

Kerkhove, R. (2014), ‘Tribal alliances with broader agendas? Aboriginal resistance in southern Queensland’s ‘Black War’, Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 6:4.

Langevad, G. (1982), ‘Some Original Views around Kilcoy, Queensland Ethnohistory Transcripts Bk 1’, The Aboriginal Perspective, Vol. 1:1.

Newspapers

‘A Page for the Boys’, The Queenslander, 6 July 1912, p. 46. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21915380.

‘An Abo Fight of ’69’, The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, 28 July 1931, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article126358285.

‘An Aboriginal Conflict’, Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 15 May 1878, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133331896.

Images

Affray of Aboriginal tribes, three miles from Brisbane, 1854. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg. No. 51288. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/1dejkfd/alma99183786913502061.

Aboriginal man with a woomera and shield at the Bloomfield River Mission, Qld, ca.1884. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg. No. 103586. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183717978802061.

Reclaiming the Land

Economic Sabotage: the Main Mode of Resistance

Aboriginal resistance was mostly economic sabotage. Realising livestock were the lifeblood of the newcomers, and experiencing dwindling food sources as settlers shot wild game, Aboriginal groups chose to frequently disperse, slaughter or maim as many cattle and sheep as they could – often by the hundreds. They similarly raided and destroyed crops, supply drays, pasture and food stores.

Some Aboriginal raiders began to live on pillaged livestock and crops. They constructed makeshift ‘bush pens’ in secluded places, to keep flocks for later consumption.

This tactic was very effective and was utilised all over Australia. Many Europeans were forced to abandon or sell their holdings on account of the continued losses and harassment. Indeed, when the Upper Brisbane and Lockyer areas were reclaimed, the main activity was dispersing and destroying livestock. The Sydney Morning Herald reported: “From their manners, and the partial conversation they have had with the white inhabitants, they seem determined to annihilate if possible the whole of the stock in the district” (10 Sept 1844, 4). Similarly, Multuggerah (one of the leaders) advised John Campbell (an early settler) that his group and their allies intended to “starve out” the settlers.

Sacking Outstations

Outstations were the ‘forward arm’ of encroaching settlement. They marked the edge of every frontier. A run’s livestock were mostly corralled here. Many outstation staff were itinerant workers or ex-convicts who in some cases took advantage of local Aborigines, especially the women. For all these reasons, the most frequent and violent Aboriginal attacks targeted outstations and the staff of outstations (hut keepers and shepherds) were the most usual victims of attacks.

In attacks on the Upper Brisbane, Darling Downs, Wide Bay and Lockyer, there were repeated cases of outstation staff (usually two or three men but sometimes several) being held in siege for days by an inter-tribal force of hundreds of warriors that had been called in through smoke signalling and other means. The warriors usually persisted in attacks until they managed to evict or kill the occupants and burn their huts and stores. Sometimes several neighbouring runs were attacked in coordinated efforts (for instance, around the MacPherson Ranges and Lockyer), or the settlers were chased from run to run (as happened at Kilcoy and Cressbrook). Such attacks were in many cases successful for a while.

Attacking Drays and Travellers

Another common tactic was threatening, attacking, robbing or killing travellers and dray (bullock cart) drivers. This included controlled burns, throwing spears at passing vehicles and conducting aggressive or abusive displays. The aim here was to disrupt and dissuade communication and transport, and reduce the flow of supplies in and out of newly settled areas.

Firing was part of Aboriginal land-management. Sometimes settlers mistook this for aggression. However, in certain cases the acts were deliberate. There are several cases where intense firing dissuaded would-be settlers from establishing themselves or forced them to move their flocks away on this account.

John Campbell recorded that Aboriginal parties considered the killing or driving away of horses as a victory, as they realised that settlers needed these to attack them or escape. Often when outstations were attacked the horses were also driven away.

For similar reasons, and because Aboriginal groups understood the importance of European letters (as they were often employed as letter-carriers and witnessed the results of such messages), there were several cases where mailmen were robbed or killed. This occurred on Stradbroke Island, near the Bunya Mountains, on the Logan, the MacPherson Ranges, and Wide Bay.

Targeted ‘Payback’ Killings

Finally, Aboriginal groups relied a great deal on single, targeted killings. This was usually payback against specific settlers for specific infringements. Often a traditional revenge party or executioner was assigned to this task, which could occur at any moment, in a sudden, surprise attack. The unpredictable nature of these killings worked extremely well in inciting terror. It was difficult for pastoralists to hire or retain staff in any place that developed a history of such killings. The actions of Dundalli between Brisbane and Caboolture were largely payback killings of this sort.

Fighting and Reclaiming

At first, aside from a few initial killings on both sides born more of fear than design, most Aboriginal groups simply stayed out of the way of Europeans. Resistance took some months or years to build

Following the Kilcoy massacre (February 1842), some 14 groups met during the “great toors” (large meetings) of 1842 and 1843 around Wide Bay and Sunshine Coast hinterland. They decided to jointly fight against settlement, vowing to “kill all whites they came across.” Word of this threat raised the fears of settlers, but in practice, killings were only enacted against particular individuals. Certain explorers and missionaries continued to freely visit, and Simpson toured much of the district during the height of this threat with a party of border police and had no encounters (presumably meaning the groups kept out of his way).

Aboriginal leadership even within a single group is mostly communal rather than singular (i.e. there was more than one leader). Each group had many factions and diverse opinions, much like American Indian tribes. Consequently, resistance went through a complex history, although there were several leaders that enjoyed unusually wide support – e.g. Commandant, Mulrobin, Moppy, Yilbung and Multuggerah.

From 1842 to 1846, large areas of the Upper Brisbane Valley, Lockyer Valley, Darling Downs and Wide Bay were sporadically reclaimed. Wide Bay was reclaimed for 3 years – the first settlers here being entirely evicted. Much of the other areas listed here were held in siege for weeks or months at a time, but eventually (after 1848) only particular pockets were still nominally in Aboriginal hands – for example, the Bunya lands, the area around Blackfellows Creek near Gatton, and Rosewood Scrub. Even many of these areas were technically held by a white owner, though in such cases the owner did not activate his use of the area.

The Bunya Bunya Reserve

A major area to be ‘reclaimed’ occurred not through violence but through diplomacy. In 1842, Andrew Petrie, who was an ally of local Aboriginals, pressured the New South Wales Governor Gipps to declare a large section to the north of Brisbane a Reserve for the exclusive use of Aboriginal groups, as the importance of the area for inter-tribal gatherings and feastings on bunya nuts was recognized and the Governor wished for the Aboriginal groups to be able to continue their lifestyles.

The area was never clearly defined but ran roughly from the Glasshouse Mountains to the North Maroochy River. The Reserve was to enclose all the bunya forests. At the time, bunya groves were only known on the Blackall Ranges but they were soon after discovered on the Bunya Mountains. Consequently, the Reserve ran for an undetermined extent west. Bunya groves as far as the Bunya Mountains continued to be protected into the 1870s.

The unexpected effect of this Reserve was to create a safe haven for Aboriginal resistance. Hostilities broke out within months of this proclamation on account of the Kilcoy massacre. The Bunya Bunya Reserve was soon seen by colonists as an entity that protected and supported Aboriginal hostility, especially when inter-tribal meetings here were regularly employed to plan attacks on whites. Although the ban on settlement in this area was maintained, border police and later Native Police were sent on patrols into the Bunya Bunya Reserve to break up (‘disperse’) gatherings and hunt for particular leaders. In 1860, one of the first moves of the newly formed Queensland government was to scrap the Reserve.

The Flow of Conflict

Generally, hostilities erupted on the edges of Upper Brisbane Valley, Lockyer Valley, the Pine Rivers / Sandgate area, Caboolture, parts of the Mary Valley, the Scenic Rim and a few sections of the Darling Downs. This was mostly adjacent to favoured hideouts or strongholds.

Archival

McConnel, A. J., ‘On Blacks’, UQFL89, McConnel Family Papers, Fryer Library, University of Queensland. https://manuscripts.library.uq.edu.au/index.php/uqfl89.

Books

Connors, L. (2015), Warrior: A Legendary Leader’s Dramatic Life and Violent Death on the Colonial Frontier, Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Journals

Kerkhove, R. (2014), ‘Tribal alliances with broader agendas? Aboriginal resistance in southern Queensland’s ‘Black War’, Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 6:4.

Laurie, A. (1959), ‘The Black War in Queensland‘, Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal, Vol.1: No.1, September, p. 157.

Conferences and Lectures

Kerkhove, R, (2014), ‘A different mode of war? Aboriginal ‘guerilla tactics’ in defining the ‘Black War’ of Southern Queensland 1843-1855,’ A paper presented July 2014 AHA Conference, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

McKinnon, F. (1933), ‘Early Pioneers of the Wide Bay and Burnett’, Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, 27 June, pp. 90-97.

Newspapers

‘Some Old Stations.’, The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), 30 January 1932, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21776319.

Images

Hamilton, George (1846) ‘Natives spearing the Overlanders cattle’, Call number V/88, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW. https://search.sl.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1ocrdrt/ADLIB110314968.

Attack on an outstation – sketch by a participant, State Library of NSW.

Hamilton, George (18??) ‘The Harmless Natives [a view of aborigines attacking a white man with spears and dragging him from his horse]’, Call number DL Pe 102, State Library of NSW. https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YK5Q4Nan.

Bullock team pulling a wagon loaded with wool from Dillalah Station, 1895, Neg. No. 62353, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/1dejkfd/alma99183505832502061.

Braddon, R. (1986), Thomas Baines and the North Australian Expedition, Sydney: Collins in association with the Royal Geographical Society.

Attack on Store Dray, plate 6 from The Australian Sketchbook 1864, S T Gill, National Gallery of Victoria. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/29428/.

Conrad Martens, Blacks camp at Gladfield December 29th 1851, Mitchell Library, State Library NSW, Call number PXC 972/Item f.10. https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/94Rw6bj1.

Individual Conflicts in SE Queensland

Battle of One Tree Hill and its Aftermath

The Battle of One Tree Hill, one of the most dramatic incidents in the frontier wars of southern Queensland, is presented in these reconstructions and images. Pitched battles between Aborigines and Europeans were rare in any part of Australia. Battles in which Aboriginal groups won were extremely rare.

According to both James Porter (who knew the participants) and the Sydney Morning Herald, the battle grew from the quandary of settlers over what to do after being evicted or severely attacked on their runs across the Lockyer region, Darling Downs and Upper Brisbane. For some months, this area – some 2500 square miles – had been much harassed by a “mountain tribes” alliance that was being led by Multuggerah, a leader from the Gatton and Upper Brisbane area. In particular, all the Lockyer runs (some 1000 square miles) were being held in daily siege at this time.

Between 14 and 16 squatters and leaseholders met at Bonifant’s Inn (on the west of what is now Gatton) to plan their course of action. They decided to draft and send a message through their local Justice (Mr Ferriter) to Dr Stephen Simpson (the Lands Commissioner) in Brisbane, requesting police assistance. As well, they organised for a “cavalcade” to be sent up from Mr Forbes in Ipswich. This consisted of 3 loaded bullock drays, with somewhere between 6 and 36 bullocks. It was accompanied by 14 armed men (mostly the settlers’ employees), and another 4 station workers and men looking for work. The track taken by the convoy was the one most subject to Aboriginal raids and attacks. It had been constructed with considerable difficulty by the settlers of the Downs and Lockyer about two years earlier. For this reason, and as it enabled commerce and communication between the Downs and Brisbane, the settlers were anxious to keep it open”. They believed they could accomplish this by increasing the number of drays, the number of assistants, and the amount of arms.

To the settlers’ surprise, Multuggerah’s men ambushed this large and well-armed “train”. The warriors had placed logs across the road to prevent the drays reversing, and additionally fenced up sides of the road with saplings tied to the trees, and created barricades. The convoy had to halt on account of all these obstacles. Whilst the dray workers were busy dismantling the obstacles at the narrowest point on the route, over 100 warriors jumped up from the creek bed they were hiding in (just beside the road). With a shout and a flurry of spears, they sent all 18 Europeans fleeing back to the inn (34 kms away). The dray was sacked of all useful goods and the warriors held a corroboree in celebration, feasting on some of the bullocks at a camp nearby.

The fleeing men took several hours to reach Bonifant’s Inn. Shocked by the ambush and embarrassed at the cowardice of their men, the settlers organised a punitive expedition. All those present at the Inn and their servants seem to have been involved – some 35 to 50 men, representing many of the runs of the Lockyer, Downs and Upper Brisbane. It was nightfall of 12 September 1843 by the time they arrived near the sacked dray. They camped some 2 kilometres from Mt Tabletop (probably junction of Blanchview and Spa Water Road).

Very early the next morning, the punitive party sought out the warriors’ camp, and surprised them whilst they were eating. They rode in and had their first battle. Quite a number of Aborigines were apparently wounded or killed, but the settlers were hampered by being bogged in the mud, and one participant was wounded in the buttocks with a spear thrown by a woman.

The majority of remaining warriors conducted a mock retreat up the rocky, steep slopes of Mt Tabletop (One Tree Hill). Apparently boulders had been stockpiled here in preparation. From this vantage point they were able to hurl spears, stones and even roll boulders. Many of the squatters’ muskets were shattered. Several of the squatter’s group were badly wounded by the stones and boulders, but no squatter was killed.

However, the 35-50 settlers were defeated. They retreated, sacking the warriors’ empty camp on their way out. They camped out near the sacked dray and waited for Dr Simpson’s border police, but when he arrived, he found the roads barricaded again. He decided that his “small force” (six men) was insufficient for the task.

This defeat was a continual embarrassment for those settlers involved. They were becoming important political figures and were not accustomed to being beaten – especially when they acted in a group. According to both local and Aboriginal accounts, the hill continued to be used as a place from which to conduct raids or roll boulders on drays camped below.

The Great Chase: Aftermath of One Tree Hill (Sept-Oct 1843)

The full maps in this section demonstrate the unusually large-scale settler response to the Battle of One Tree Hill. This was a campaign of chasing Multuggerah’s warriors out of Helidon and into Rosewood Scrub, with sniping and raids by both sides, en route and after.

Immediately following the battle of One Tree Hill, Dr Simpson returned to Ipswich and Brisbane to gather forces. He obtained two lands commissioners, three other officers, a dozen soldiers and “a force of locals” to which he added his six mounted police. This was probably a total of 35-45 men. Meanwhile, the 16 station owners and/or overseers from the Inn, representing many of the runs on the Darling Downs, Lockyer and Upper Brisbane, returned over a back road (Flagstone Creek Road) to their respective homes and sent form messages to gather their own forces all over the district. Some came from as far as Cressbrook. They included station heads, servants, workers and three bush constables. This was perhaps another 40 to 60 men. Thus in total some 75 to 100 settlers, including most of Moreton Bay’s soldiers and police, chased Multuggerah’s warriors from the pass.

It is recorded that one of these parties camped at Helidon. Multuggerah’s group was forced 50 kilometres along the creek and river valleys and ridges, availing themselves of broken and densely wooded areas to evade their pursuers. They headed for Rosewood Scrub – a 159 square miles of vine forest that once existed around Laidley, Plainlands, Lowood and Rosewood. For the entire distance, they were sniped at by the European forces, but they had the advantage of rough terrain and their superior knowledge of the district, which impelled their pursuers to follow on foot.

For the next couple of weeks, Multuggerah’s warriors successfully hid in the Rosewood Scrub, where their assailants failed to locate them. They also continued raids on the settlers. The most daring of these involved some 60 to 80 warriors attacking a head station near Ipswich, belonging to Mr McDougall. The huts and stores were plundered, most belongings destroyed, and the staff were driven off at spear point, being told “to be off, as it was their ground”. Eventually, using an Aboriginal tracker, the squatters located and stormed the main base camp in the scrub, killing leaders and an unknown number of others. This was in October 1843. They also destroyed large quantities of stockpiled weapons. Nevertheless, attacks and raids continued for another 5 years, with the Rosewood and Helidon Scrubs serving as the main base for activities.

Corn Fields Raids 1827 – 1828

The very first frontier conflict of Queensland consisted of Aboriginal hostilities near the fledgling colony at Redcliffe (near today’s Humpybong Park) in 1824. Aborigines killing and threatening convicts at Yebri Creek and elsewhere seems to have been part of the reason for the removal of the colony to Brisbane.

Three years later, the same hostilities threatened the colony at its new location (today’s Brisbane CBD). This consisted of repeated plundering and destruction of the maize fields at South Brisbane, New Farm and Kangaroo Point. The Aboriginal community realised that this was the colony’s main supply food. Thus from 1827 onwards, they organised themselves to starve out the settlement:

…a disposition was evinced, on the part of a tribe of the black natives, to pillage or destroy portions of the second maize crop, then in the ground… a party of natives… appeared… to be meditating a fresh invasion (The Australian 25 July 1827:3).

Sets of 40 to 50 southside warriors from the camps at Woolloongabba and South Brisbane descended on the fields in regular, continuous raids. Mulrobin was the main southside warrior and headman at this time and most likely orchestrated the attacks. Indeed, an 1838 account mentions the fame of his “warlike feats”. The raiders destroyed and sometimes took large quantities of corn and sweet potato.

After a series of smaller raids that had been deflected by posting a single gunman, a successful attack was launched on the evening of 24 April 1827. The raiders this time waited till the corn was nearly ripe. They tossed several spears at the watchman, wounding his hand and forcing him to flee. As the fields were now under Aboriginal control, Logan sent over three men to fire over their heads, but this had little effect. Rather, they began to gather in what Logan described as “alarmingly large numbers”. By 8pm – using the darkness to cover them – a very large force charged en masse into the fields.

Logan was apparently watching all this from across the river. He was concerned the entire crop would be destroyed, leaving the settlement bereft of food until the next supply ship. Noticing the failure of the three gunmen to control the situation, he sent over another two constables and three soldiers – making a party of eight trying to curb the raid in pitch darkness.

The soldiers spotted two escaped convicts amongst the raiders and focussed on these, eventually tracking them to the main camp (probably Woolloongabba). Here they tried to apprehend the escapees, who were now sitting around one of the camp fires. In the darkness and confusion, the convicts escaped. Naturally, with the entrance of soldiers at the camp, warriors flew into defence. There was some sort of skirmish, in which at least one warrior was shot dead.

As a result of all this, Captain Logan instituted a series of “crow minders” – convicts who watched the fields from treehouse shelters. They were day and night sentinels. During small raids that followed that of 24 April, the sentinels are known to have shot and killed at least one warrior, and probably wounded many.

But Mulrobin’s men carefully noted who conducted the shootings. Several months later (6 January 1828) his warriors stalked and killed both South Bank crow minders and severely wounded another man whilst they were making a recreational excursion into the south (roughly the Logan River area).

Thus, despite crow minders, corn field raids continued. A convict workman was speared very close to where a sentinel kept watch. A second major raid followed – again just as the corn was ripening (24 January 1828). In this attack, warriors rushed the South Bank fields in broad daylight. One of the raiders was killed. The crow minders seem to have persisted into the 1830s. Tom Petrie mentions one who watched over their gardens (near today’s Customs House), always keeping a loaded rifle handy.

Stradbroke and Moreton Islands 1832 – 1833

There are three rather conflicted written accounts of conflict between soldiers and Aboriginal groups, roughly between 1832 and 1833. Oral traditions of the Aboriginal residents add further details.

The conflict seems to have erupted over killings and counter-killings involving the European staff of the Amity Point pilot station and a local headman, who was killed during a fishing trip. According to one account (of Thomas Welsby) the result was a day-long pitched battle against a group of soldiers at the flats of Cooroon Cooroonpah Creek (north of Myora).

Although the accounts of the Battle of Cooroon Cooroonpah Creek differ in details, they indicate that the conflict began with the Amity Point Pilot Station. After a few payback killings at Point Lookout and Dunwich for the abduction of Aboriginal girls and the killing of a headman, soldiers were sent from the mainland, attacking camps on the southern end of Moreton Island and purportedly killing some 15 to 20 Aborigines. The conflict came to a peak with a day-long pitched battle north of Myora (at Cooroon Cooronpah Creek) between soldiers and warriors. It seems to have ended in a stalemate, and accounts vary as to casualties – some listing a couple of soldiers being killed, other accounts saying no one died on either side. Quandamooka oral history is that Dunwich Cemetery was begun with some of the dead warriors from this battle.

The long grass of this location and the clunky nature of muskets (which took time to reload) enabled the warriors to sneak up repeatedly on the soldiers. The battle purportedly established some of the terms of cooperation that the Stradbroke people thereafter maintained with white settlement.

Pine Rivers/Sandgate Area 1850 – 1860

The Pine Rivers/ Sandgate area is of interest as an arena of conflict during the 1850s. On account of the rainforest and wetlands skirting the South Pine – which was used as a pathway by Aborigines – Pine Rivers was somewhat of a bastion or safe haven for Aborigines. Settlers purchased land at Pine Rivers and Sandgate but were repeatedly ousted, most notably from Sandgate and Cash’s property, which was boldly situated in the middle of this region. The first settlement of Bald Hills sat on a ridge overlooking these dangerous flats– the huts reportedly being placed within close proximity for safety. The settlers were regularly visited by police to monitor their progress.

Chas Melton described the area as home to thousands of hostile Aborigines. The most troublesome groups, such as friends and companions of the warrior-leaders Dundalli and Yilbung – generally passed through this area between Brisbane and Bribie Island, reportedly taking whatever they wished from people’s homes and gardens, even in daylight.

For this reason, the Native Police headquarters for all of southern Queensland was established at Sandgate in 1861. From here, Ltnt Fred Wheeler and his troops patrolled into the Caboolture district and beyond. Sometimes they were called to deal with situations in Bald Hills.

Breakfast Creek Camp Raids 1840 – 1860

Aboriginal groups still remember Breakfast Creek as a type of ‘front line’ in their battle against encroaching settlement. The large and prosperous camps had been commented upon as early as 1824 by Oxley and Cunningham. Leaders such as Yilbung, Commandant, Dalaipi, Dundalli, Billy Barlow, Harry Pring and Tinkabed were all visitors here.

In 1852, 40 warriors raided Mr Bullocks’ home, destroying crops. They then joined a party of 200 to attack Cash’s property further north. A large party of settlers and eight mounted troopers responded by attacking the camps, but they became bogged and found the camps empty on their arrival. They nevertheless burnt down and destroyed what they could.

Between 1856 and 1867 there was continual harassment, raids and robberies by Aboriginal groups here, resulting in a series of punitive attacks by settlers. In 1859 five police destroyed the camps and killed and injured at least two of the over 100 residents. In 1861, riotous Aborigines drove off drays and robbed travellers, resulting in Constable Griffin and two mounted police raiding Aboriginal camps and making arrests. In 1862 there was another “dispersal” by Constable Griffin and one trooper. In 1865 two Constables were attacked and in revenge for this Aboriginal camps were again burnt down. In 1867, some 15 Aborigines stole one boat and ransacked another (a cutter). Sub-Inspector Gough conducted the fourth burning of the camps. Similarly, in 1874 mounted police dispersed camp occupants.

Rosewood Scrub 1843 – 1848

Rosewood Scrub covered a large area. As this map indicates, it held many camping grounds, ceremonial grounds and other sites. It had a tangled wall of brigalow so marked that it was often drawn on local maps. As access was so difficult and many Europeans became lost travelling through here, it remained a favoured bastion for resistance throughout the 1840s and even saw use as a hideout many decades later, until German farmers began the arduous task of clearing it to establish dairy farms.

From 1843 to 1846, Multuggerah continued his attacks on drays and travellers from this location as well as from the Downs. Rosewood Homestead (now Glenore Grove) was repeatedly held in siege, which according to one report resulted in settlers building a makeshift ‘fort’ here that they took turns manning.

In 1846, Multuggerah brought some 500 warriors and almost starved out the Rosewood Homestead occupants. The settlers were relieved by accidental visitors. The combined party later stormed Multuggerah’s camp, killing him and many others. In the next years (1846-1848), other leaders such as Jackey, Uncle Marney and possibly King Billy seem to have operated from here.

Immediately after the Battle of One Tree Hill, Lands Commissioner Simpson established a soldier’s barracks or fort near Postman’s Ridge to guard the road up the Downs. This fort seems to have been moved a couple of times. It was manned with anything from 3 to 13 soldiers from the 99th Regiment . Travellers and drays camped along the creek by this checkpoint. From here, they had to wait for a soldier to escort their convoy up through the pass. The fort was disbanded in June 1846. There was also purportedly a barricaded building at Rosewood Homestead (now Glenore Grove) with a similar defensive purpose, built and manned by settlers.

Brisbane Northside 1840 – 1850

Northside Brisbane was a contested landscape in the 1840s-1860s. As shown on the accompanying map, creeks served as de facto borders which Aboriginal parties – if troublesome or threatening – were sometimes driven across by police. Aboriginal oral traditions recall areas beyond these points as places where they could camp and hunt unmolested. This de facto situation meant that in the view of Aboriginal families, any settlers present beyond the creeks were trespassers. This may explain the continual harassment, robbery and violence experienced by Europeans who ventured beyond these points during the 1840s-1860s.

However, none of this was officially ordained. Settlement continually expanded. From the dawn of settlement onward, civic and policing authorities did not designate any areas in or near Brisbane for Aboriginal camping or any other Aboriginal use. Nevertheless, numerous reminiscences and contemporary accounts attest to the fact that in practice, European residents allowed traditional camping grounds to remain, regardless of who owned the area. This was the case sometimes into the 1890s-1910s and later in places such as Victoria Park, Holland Park and Nundah.

Victoria Park was a very major camp, often seeing hundreds of residents. It is of interest as a conflict site because it saw shootings and burning of camps – first by Constable Peter Murphy and his party in 1846, then by 24 soldiers of the 11th Regiment in 1849.

Nearby lay Wickham Park. In 1846 and 1847, one warrior-leader, Yilbung, took a monthly ‘rent’ of the Colony’s flour – extracting regular bags for his people from the mill workers at the Windmill. Yilbung was imprisoned for this. In 1855 the Windmill site was also where Aboriginal groups staged a very vocal protest during the hanging of Dundalli, a warrior who was seen as a hero and leader by many from the northside and Bribie areas.

Nundah saw Aboriginal raids and attacks on its German Mission – most notably in 1840 when some 20-30 warriors sacked Reverend Schmidt’s fields, forcing the mission to keep nightly armed watch over the crops. Partly in retaliation, Reverend Schmidt shot and wounded a number of elders. In 1850 cattle were harassed and in 1854, 60 warriors surrounded a homestead and pulled up all its crops.

In 1858, Nundah settlers became frightened of a war-making corroboree and the voiced threats of Aboriginal warriors. They decided on a preemptive strike. With some police in assistance, a group of settlers crossed the swamp at night to one of the Nundah camps (probably the old Cemetery site) and fired a volley of shots into the camp. Casualties are unknown but the camp was abandoned for two months. The surviving occupants took revenge by dispersing and killing numerous cattle on the Pine Rivers.

References

Primary Sources

Armstrong, J. (1975), Pine Rivers Local History Collection, Tape by John Armstrong for National Estate of Pine Rivers (Miss Joyner No 13: Aborigines, 20.6 p. 2).

John Oxley Library Collection, OM 83-21 Box 914, Evans, G.V., ‘The Rosewood Scrub’ .

John Oxley Library Collection, John Goodwin Records, TR 1823, Goodwin, M. (1984), ‘From the Journal of Dr John Goodwin (1843)’.

Queensland State Archives, Inquest file, ITM348614, 1867, No. 9. (Previous identifier JUS/N15/67/9).

Books

Anderson, R. (2001), History, Life and Times of Robert Anderson Gheebulum, Ngugi, Mulgumpin, South Brisbane: Uniikup.

Bond, A. (2009), The Statesman, The Warrior and the Songman, Nambour: Alex Bond.

Campbell, J. (1936), The Early Settlement of Queensland, Brisbane: Bibliographic Society of Queensland.

Carter, P. Durbidge, E. and Cooke-Bramley, E. (eds) (199?), Historic North Stradbroke Island, Dunwich: North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum.

Connors, L. (2015), Warrior: A Legendary Leader’s Dramatic Life and Violent Death on the Colonial Frontier, Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Egan, Allen Joe et al. (2010), Nundah: Mission to Suburb, Nundah: Joe Egan.

Kerkhove, R. (2015), Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane: An Historical Guide, Salisbury: Boolarong.

Kerkhove, R. (2016), Multuggerah and Multuggerah Way, Brisbane: Jagera Daran & Catholic Justice Commission.

Langevad, G. (1979), The Simpson Letterbook – Historical Records of Queensland No 1, St Lucia: University of Qld (Anthropology Museum).

Meston, A. (Jan 1895), ‘Moreton Bay and Islands’, Paper read at the Australian Association for the Advancement of Science, Brisbane.

Nelson, C. J. (1993), The Valley of the Jagera – The Lockyer Valley, Gatton: Chris Nelson.

O’Keefe, M. (1975), Some Aspects of the History of Stradbroke Island, Brisbane.

Petrie, C. C. (1904), Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & Co, pp. 159, 231, 260.

Queale, Alan (1978), The Lockyer- Its First Half Century, Gatton: Gatton & District Historical Society.

Richards, J. ‘Frederick Wheeler and the Sandgate Native Police Camp’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol 20 (2007), p. 110.

Rieck, A. (2015), Rosewood Scrub Arboretum – Peace Park, Rosewood, Rosewood: West Moreton Landcare Group.

Russell, H. (1888), The Genesis of Queensland, Sydney: Turner & Henderson. https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1305181h.html.

Snars, F. (1997), German Settlement in the Rosewood Scrub – A Pictorial History, Gatton: Rosewood Scrub Historical Society.

Steele, J. G. (1975), Brisbane Town in Convict Days 1824-1842, Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Stevens, E. V., ‘Early Brighton and Sandgate’, (Read at a meeting of the Queensland Royal Historical Society August 23 1956).

Talbot, Don, revised Don Neumann, (2014), A History of Gatton & District 1824-2008, Gatton: Lockyer Valley Regional Council.

Teugue, D. T. (1972), The History of Albany Creek, Bridgeman Downs and Eaton’s Hill, Albion: Colonial Press, p.16.

Tew, A. (1979), History of the Gatton Shire in the Lockyer Valley, 1979, Gatton: Gatton Shire Council.

Uhr, F. (2009), The Day the Dreaming Stopped: A Social History investigating the sudden impact of the pastoral migration in the Lockyer and Brisbane Valleys 1839 to 1846, MA Coursework MSS (University of Qld).

Watkins, G. (1891), ‘Notes on the Aboriginals of Stradbroke and Moreton Islands’, Brisbane: Royal Historical Society of Queensland. https://archive.org/details/notesontheaboriginalsofstradbrokeandmoretonislandsbygeorgewatkins/page/n5/mode/2up.

Welsby, T. (1940), Moreton Bay Natives: Tribes Now Extinct.

Welsby, T. (1922), Memories of Amity, Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson and Co.

Whalley, P. (1987), An Introduction to the Aboriginal Social history of Moreton Bay South East Queensland from 1799 to 1830, Brisbane: Peter Whalley

Journals

Dawson, Chris (comp.), (2009), ‘Random Sketches by a Traveller through the District of East Moreton (January-March 1859)’, Colonial Columns No.1, Fairfield: Inside History, p.6.

Evans, Ray (2008), ‘On the Utmost Verge: Race and Ethnic Relations at Moreton Bay, 1799-1842’, Queensland Review Vol 15:1, pp. 1-31.

Uhr, F., ‘The Raid of the Aborigines; a brief overview and background to the poem’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland Vol 17: 12 (Nov 2001).

Uhr, F., ‘September 12 1843: The Battle of One Tree Hill – A Turning Point in the Conquest of Moreton Bay’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol 18:6 (May 2003), pp. 241-255.

Museums

‘History and Ecology of the Rosewood Scrub’ (198?), Rosewood Scrub Museum Folders (No.3, Rosewood Tallegalla), pp.1-5.

Kleidon, F. (1979), ‘Early Settlers’ Arrival’, Rosewood Scrub Museum Folios, Bk.7 – Settlers and History, pp. 3-5.

Reports

Blake, T. (2000), Historical Context Report – Western Region Research Project, Brisbane: FAIRA.

Gentz, Allen M. (2012), ‘Ground Penetrating Radar Investigation of the Convict Barracks, Dunwich, North Stradbroke Island, Queensland, Australia’, Report to North Stradbroke Historical Museum.

Kerkhove, R. (2015), Report: Indigenous Use and Indigenous History of Rosewood Scrub, Brisbane: Jagera Daran.

Newspapers

Australian, ‘Affray with Natives at Moreton Bay’, 25 July 1827, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37072390.

Bathurst Advocate, ‘Moreton Bay’, 3 June 1848 p. 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62044964.

Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, ‘The Raid of the Aborigines’ (Continued from Our Last), 11 January 1845, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article59764296

Brisbane Courier, ‘Weekly Epitome’, 28 October 1865, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1281161.

Brisbane Courier, ‘Supreme court’, 4 March 1869, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1301328.

Brisbane Courier, ‘Personal’, 29 July 1913, p. 9. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19895457

Brisbane Courier, ‘When Woolloongabba was Wattle-Scented – Old Pioneers and Predatory Blacks’, 18 June 1921, p. 16. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20460962.

Brisbane Courier, ‘The Late Mrs McPherson’, 20 May 1922, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20542653.

Brisbane Courier, Charles Duncan, ‘A Pioneer’s Recollections. Brisbane in 1857 – No. 1’, 13 October 1923, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20658458.

Brisbane Courier, Charles Duncan, ‘A Pioneer’s Recollections. Brisbane in 1857 – No. 2’, 27 October 1923, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20649476

Brisbane Courier, ‘Personal’, 19 April 1919, p. 15. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20359780.

Brisbane Courier, ‘By the Pleasant Watercourses’, 19 March 1927, p. 23. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21127860

Brisbane Courier, Scott, R. J., ‘100 Years Ago’, 12 April 1930, p. 12. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21527743

Brisbane Courier ‘Hamilton and Ascot’, 27 September 1930, p. 21. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21588012.

Colonial Times (Hobart), ‘Moreton Bay’, 20 April 1852, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8771251.

Courier, ‘Brisbane Agricultural Reserve’, 24 June 1861, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4599568.

Courier, ‘Legislative Assembly’, 25 July 1861, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4600131.

Courier, ‘Local Intelligence – Turning the Tables’, 17 August 1861, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4600551.

Courier, ‘Local Intelligence – Outrages by the Blacks’, 17 December 1861, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4602792.

Courier, ‘Local Intelligence – The Blacks’, 29 January 1862, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4603601.

Courier, ‘Local Intelligence’, 29 January 1863, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3161181.

Courier, ‘Local Intelligence’, 23 February 1863, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3161669

Courier, ‘Letters – The Poor Blacks and the Police’, 9 January 1864, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3167910.

Courier Mail, ‘The Genesis of Bald Hills’, 12 May 1934, p. 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36728917

Courier Mail, Clem Lack, ‘Sandgate’s Pioneers Carried Loaded Guns’, 22 July 1950, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49733545.

Daily Mail, ‘The Petries – ‘Historic Family – Blazing the Trail’, 31 July 1924, p. 21. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219053679.

Empire (Sydney), ‘Moreton Bay’, 27 January 1852, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60127309.

Empire (Sydney), ‘Moreton Bay’, 6 October 1856, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article64977640.

Empire (Sydney), ‘Supposed Murder at the German Station’, 27 March 1869, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60833248.

Freeman’s Journal (Sydney), ‘Intercolonial News – Queensland’, 26 May 1866, p. 330. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115453091.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘The Aboriginals’, 3 August 1850, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3713114.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Domestic Intelligence’, 17 September 1853, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3710129

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Domestic Intelligence’, 24 October 1857, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3722656.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Domestic Intelligence’, 31 October 1857, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3717381.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Domestic Intelligence’, 21 November 1857, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3716773.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Domestic Intelligence’, 27 January 1858, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3717722.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘Separation – Natives’ Love for Sheep’, 3 November 1858, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3725801.

Moreton Bay Courier, Sheridan, R. B., ‘Mr. Sheridan’s Account of the Search for the Missing Men’, 9 February 1859, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3724782.

Moreton Bay Courier, ‘The Life and Opinions of Thomas Jefferson – Cruelty to the Blacks’, 10 September 1859, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3719940.

North Australian, Ipswich and General Advertiser, ‘Brisbane’, 10 January 1860, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77428861.

North Australian and Queensland General Advertiser, ‘Brisbane’, 1 August 1863, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77293698.

Queenslander, Knight, J. J., ‘In the Early Days – XI’, 27 February 1892, p. 402. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19821754.

Queenslander, ‘News of the Week’, 9 February 1867, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article20311797.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘News from the Interior – Moreton Bay’, 22 March 1845, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12878223.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Moreton Bay’, 7 February 1855, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12965307.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Moreton Bay’, 14 August 1855, p. 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12972862.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Moreton Bay’, 20 May 1856, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12977543.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘To the Editor – The Aborigines and the New Settlers’, 30 November 1857, p. 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28633596

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Queensland’, 19 September 1859, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13030953

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Queensland’, 26 September 1859, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13031215.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Queensland’, 19 November 1861, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13067297

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Queensland – The Aborigines’, 9 December 1861, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13058075.

Sunday Mail, Lack, Clem, ‘When Blacks Roamed Lutwyche’, 18 September 1938, p. 40. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article98004124.

Telegraph, ‘Blacks at Cash’s Crossing’, 29 April 1936, p. 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article183388718.

Images

Mount Tabletop (One Tree Hill) near Toowoomba (Image courtesy of Toowoomba Regional Council).

Roughly constructed bush pub with horses’ hitching rail in front, Queensland, JOL SLQ Neg. No. 202418. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183510011502061.

S T Gill 1818 – 1880 / Wool drays (from ‘The Australian sketchbook’) 1865, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. https://collection.qagoma.qld.gov.au/objects/1207.

Sketch of the ‘Chase’ by Thomas Domville-Taylor, Patty Ffoulkes Scrapbook 1840-1844, NLA. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/4970818.

Woody Point shoreline ca. 1876, JOL SLQ Neg. No. 196831. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183788015102061.

Early drawing of a section of the town of Brisbane, Queensland including the Convict Hospital, 1835, JOL SLQ Neg. No. 138146. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183506538602061.

Town of Brisbane by Henry Wade in 1844, QSA Item ID ITM714289. https://www.archivessearch.qld.gov.au/items/ITM714289.

Amity Point Pilot Station, Redland City Council. ‘Quandamooka: Local history as recorded since European settlement.’ Redlands Coast Timelines, Redland Libraries.

https://www.redland.qld.gov.au/download/downloads/id/3982/quandamooka_timeline.pdf.

Map of the Cooroon Cooroonpah Creek area, Stradbroke, Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying. https://www.qld.gov.au/recreation/arts/heritage/museum-of-lands.

Plans and sections of out station, Dunwich, QSA Item ID ITM 659609. https://www.archivessearch.qld.gov.au/items/ITM659609.

Dundalli, Silvester Diggles Sketch Book, 1855. https://harrygentle.griffith.edu.au/projects/silvester-diggles-sketch-book/.

Native Police detachment, Queensland Police Museum, No. PM2431.

Early map of Breakfast Creek, Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying. https://www.qld.gov.au/recreation/arts/heritage/museum-of-lands.

The 1850 petition of residents at or near Breakfast Creek pleading for police protection, QSA.

Hamilton Reach, Brisbane, ca. 1888, JOL SLQ Neg. No. 204328. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183512877102061.

1840s Blockhouse, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockhouse.

Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, a distance of upwards of 3000 miles, during the years 1844-1845, Project Gutenberg eBook. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5005.

York’s Hollow, Brisbane, 1864, JOL SLQ Neg. No. 108131. https://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/permalink/61SLQ_INST/tqqf2h/alma99183505156502061.

Medal- Sandy ex Rex Queensland, New South Wales, Australia, 1877, Museums Victoria Collections, Item NU 33473. https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/146899.

Selected References

Ayres, M. L. (2011), ‘A Picture asks a Thousand Questions,’ The National Library Magazine, June 2011, pp. 8-11.

Bracewell, J. (1842), ‘Statement of Bracewell & Davis as to the Supposed Administration of Poison to Some Blacks by White Men,’ in Simpson Letterbook, ed Gerry Langevad, ‘Some Original Views around Kilcoy’, Queensland Ethnohistory Transcripts, Bk 1:The Aboriginal Perspective, Vol. 1:1, 1982, p. 5.

Bartley, N. (1896), Australian Pioneers & Reminiscences, Brisbane: Gordon & Gotch. https://www.textqueensland.com.au/item/book/47a2c6b5172104e50ae1d25ea425ac3b.

Bennie, J. C. (1931), ‘The Bunya Mountains – Early Feasting Ground of the Blacks’, The Dalby Herald, 13 February 1931, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217542226.

Bloomfield, G. (1986), Baal Bellbora: The End of the Dancing, Chippendale: APCOL.

Bottoms, T. (2013), Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times, London: Allen & Unwin.

Brisbane History Group and Fisher, R. (1990), Brisbane: the Aboriginal presence 1824-1860, Brisbane, Qld.: Brisbane Historical Group.

Campbell, J. (1936), The Early Settlement of Queensland, Brisbane: Bibliographic Society of Queensland.

‘Christmas among the Pioneers of Moreton Bay‘, The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba), 24 December 1875, p. 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77765076.

Clark, W. (1912), ‘Explorer Walker – Organiser and First Commandant of the Native Police’, The Brisbane Courier 28 December 1912, p. 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19830766.

Connor, J. (2002), The Australian Frontier Wars 1788-1838, UNSW Sydney 2002.

Connor, J. (2004), The Tasmanian Frontier and Military History, Tasmanian Historical Studies, Vol. 9.

Connors, L. (2005), Indigenous resistance and traditional leadership: understanding and interpreting Dundalli, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 19:3.

Dansie, R. (1990), Toolburra: the Conditions and Prospects of the Native Tribes: Stories, opinions, events and reports concerning the aborigines in the Darling Downs and Moreton Districts, Toowoomba: Toowoomba Education Centre.

Darragh T. A. & Roderick J. Fensham (eds) (2013), The Leichhardt diaries – Early Travels in Australia during 1842-1844, Memoirs of the Queensland Museum Culture, Vol. 7:1, Brisbane 2013, 30 July 1843, p. 266.

Dennis, P., Heffrey Grey, Ewan Morris, Robin Prior, John Connor (1995), Aboriginal Armed Resistance to White Invasion, The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, Melbourne: Oxford University.

Evans, R. (2002), ‘Against the Grain: Colonialism and the Demise of the Bunya Gatherings, 1839-1939’, Queensland Review, No.9:2, Nov 2002, p. 64.

Foley, D. (2007), ‘Leadership: the quandary of Aboriginal societies in crises, 1788-1830, and 1966’, in Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (ed.), Transgressions: critical Australian Indigenous histories, ANU ePress, Canberra Australia, pp. 177-192.

French, M. (1989), ‘Conflict on the Condamine: Aborigines and the European Invasion: a history of the Darling Downs Frontier’, Vol. 1, Toowoomba: Darling Downs Institute.

Goodwin, M. (1843/ 1984?) JOL, ‘From the Journal of Dr John Goodwin (1843),’ John Goodwin Records, OM Box 5327.

Hodgson, C. P. (1846), Reminiscences of Australia with Hints of the Squatters Life, London: W. N. Wright.

Guthrie, M. (1927), ‘By the Pleasant Watercourses’, The Brisbane Courier, 19 March 1927, p. 23. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21127860.

Howitt, A. W. (1904), The Native Tribes of South-east Australia London: MacMillan & Co.

Jarrott. J. K. (1976), ‘Gorman’s Gap,’ Queensland Heritage, Vol. 3:4, pp. 24-38.

JOL Box 7072 Karl W. E. Schmidt (1843), Report of an Expedition to the Bunya Mountains in Search of a Suitable Site for a Mission Station, p.5, Acc 3522/71.

Kerkhove, R. (2012), The Great Bunya Gathering – Early Accounts, Enoggera: Pemako.

Kerkhove, R. (2014), ‘A different mode of war? Aboriginal ‘guerilla tactics’ in defining the ‘Black War’ of Southern Queensland 1843-1855,’ A paper presented July 2014 AHA Conference, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Kerkhove, R. (2014a), ‘Tribal alliances with broader agendas? Aboriginal resistance in southern Queensland’s ‘Black War.’ Journal of Cosmopolitan and Civil Societies, (UTS), Vol. 6:3.

Kerkhove, R. (2015), ‘Barriers and Bastions: The Fortified Frontier and Black and White Tactics,’ Our Shared History: Resistance and Reconciliation,’ CQU (Noosa) online. https://www.academia.edu/13032599/Barriers_and_Bastions_Fortified_frontiers_and_white_and_black_tactics.

Kerkhove, R. (2016), Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane, Brisbane: Boolarong.

Kerkhove, R. (2016), Multuggerah and Multuggerah Way, Brisbane: Jagera Daran & Catholic Justice Commission.

Knight, J. J., Sketcher: In the Early Days – XI. The Birth and Growth of Brisbane and Environs. Bold Speculators, The Queenslander, 27 February 1892, p. 402. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19821754.

Langevad, G. (1979), The Simpson Letterbook – Historical Records of Queensland No 1, St Lucia: University of Queensland (Anthropology Museum). https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:289630.

Langevad, G. (1982), Some Original Views around Kilcoy, Queensland Ethnohistory Transcripts Bk 1: The Aboriginal Perspective Vol. 1:1.

Laurie, A., (1959), UQ Fryer MSS, ‘The Black War in Queensland’ in Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 6:1 pp. 155-173.

Lergessner, J. G. (2007), Death Pudding: The Kilcoy Massacre, Kippa Ring: James Lergessner.

McConnel, A. J. (1843), ‘The Aborigines,’ Hayes Library MSS 89/206.

McConnel, A. J., (1932), ‘Some Old Stations No 2′, Brisbane Courier, 30 Jan 1932, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21776319.

McKinnon, F. (1933), Early Pioneers of the Wide Bay and Burnett, Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, on June 27, 1933, pp. 90-97.

‘News and Notes – By a Sydney Man, No. XXVII’, The Brisbane Courier, 9 August 1865, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1276516.

‘News from the Interior, Moreton Bay’,. The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 October 1843, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12408181.

Orsted-Jensen, R. (2011), Frontier History Revisited – Colonial Queensland and the ‘History War,’ Lux Mundi: Brisbane.

Petrie, C. C . (1904), Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & Co.

Porter, James (1911), ‘Interesting Reminiscences’, Darling Downs Gazette, 21 Jan 1911, p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article182699212.

Pugh, T.P. (1859), Pugh’s Moreton Bay Almanac, 1859, Brisbane: Theophilis P. Pugh.

Reynolds, H. (1982), The Other Side of the Frontier, Ringwood: Penguin.

Reynolds, H. (2013), Forgotten War, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Richards, J. (2007), ‘Frederick Wheeler and the Sandgate Native Police Camp,’ Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 20.

Richards, J. (2008), The Secret War: A True History of Queensland’s Native Police, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Rolleston, R. (1913), ‘Early Queensland Reminiscences,’ The Australasian, 15 Nov 1913, p. 6.

Russell, H. (1888), The Genesis of Queensland, Sydney: Turner & Henderson, online Gutenburg eBook. https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1305181h.html.

Ryan, L. (2013), Untangling Aboriginal resistance and the settler punitive expedition: the Hawkesbury River frontier in New South Wales, 1794–1810, Journal of Genocide Research, Vol. 15:2, pp. 219-232.

Schmidt, Karl W.E. (1843), Report of an Expedition to the Bunya Mountains in Search of a Suitable Site for a Mission Station, p.5, Acc 3522/71 in Box 7072, JOL.

Some Old Stations. No. II. The Early Records. The Brisbane Courier, 30 January 1932, p. 19. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21776319

Steele, J. (1984), Aboriginal Pathways in southeast Queensland and the Richmond River, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

T.W.A., Helidon. Stray notes of birds, the hum of bees, The brook’s light gossip on its way; And spring-time leaves all glistening in the breeze, Queensland Country Life, 23 August 1900. p. 14. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101452629.

Talbot, D. (2014), A History of Gatton & District 1824-2008, Gatton: Lockyer Valley Regional Council.

The Book of trails for the Moreton Bay penal settlement, Brisbane: Oxley Memorial Library, John Oxley Library, 1910.

‘The Raid of the Aborigines (Continued from Our Last)’, Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 11 January 1845, p 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article59764296.

Uhr, F. (2001), ‘The Raid of the Aborigines; a brief overview and background to the poem,’ Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol 17:12.

Uhr, F. (2003), September 12 1843: The Battle of One Tree Hill – A Turning Point in the Conquest of Moreton Bay, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Vol. 18:6, pp. 241-255.

Uhr, F. (2009), The Day the Dreaming Stopped: A Social History investigating the sudden impact of the pastoral migration in the Lockyer and Brisbane Valleys 1839 to 1846, MA Coursework MSS (University of Queensland).

Veracini, L. (2002), ‘Towards a further redescription of the Australian pastoral frontier’, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol 26:72, pp. 29-39.

Wallin Ann & Assoc, Sept 1998, Helidon Hills: A Predictive Cultural Heritage Report (for Westroc) Archaeo.

Windschuttle, K. (2002), The Fabrication of Aboriginal History (Vol.1), Paddington: Macleay.